The freewheeling, funky title track on Jon Cleary’s latest album was tracked live, including keeper vocals, in The Parlor studio (New Orleans). But that’s the exceptional song that proves the rule: Cleary actually takes an extremely methodical approach to record-making.

Known best as a New Orleans-style piano player, Cleary is an accomplished multi-instrumentalist and recordist. As he explained to Keyboard magazine in June, he creates homemade versions of his songs first in FHQ (Funk Headquarters), his personal studio: “I play the drums, bass, guitar, keyboards, all the vocal parts. I’ll spend a long time doing that and then redoing it—scrapping stuff and getting it to a point where I think it’s good.”

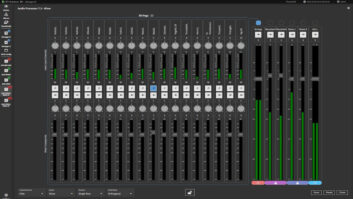

Cleary’s studio is situated in the basement of his home—a converted hardware store—in New Orleans’ Bywater neighborhood. It’s fitted with a Sony DMX-R100 console, Pro Tools 10 system, Vintech 1272 mic pre’s, and his choice mics and instruments.

When his DIY versions of the Dyna-Mite songs were complete, Cleary sent them to the musicians that he and producer John Porter had chosen to appear on the album. “They’re all great musicians. I lived in L.A. for years and worked with all the first-call guys in L.A.,” says Porter. “I would say that these New Orleans guys would be first-call anywhere.”

Guitarist Shane Theriot, bass player Calvin Turner, keyboardist Nigel Hall, drummer Jamison Ross, and horn players Charlie Halloran (trombone), Ryan Zoidis (tenor sax) and Eric Bloom (trumpet) learned the songs and developed some of their own ideas within Cleary’s framework. After that, the group finally got together in the Music Shed, one of New Orleans’ most in-demand commercial studios. Engineering was the Music Shed’s former chief engineer, Michael Dorsey.

Classic Tracks: The Smiths, “What Difference Does It Make?” by Barbara Schultz, Sept. 8, 2010

Cleary’s purpose at that point was to capture what the musicians would bring to his songs so that later he could choose his favorite performances from among his solitary recordings in FHQ, or from the band sessions in the Music Shed or The Parlor, or more cuts that were made back at FHQ toward the end of the recording process.

The production team of Cleary, Porter and Dorsey remained consistent from studio to studio, and so did many of the equipment choices. For example, Dorsey likes Shure KSM44 microphones on acoustic piano, and the setup for capturing keyboards was similar in all three tracking facilities.

“In Music Shed, Jon played a Nord Electro 2 and a Roland RD-500. I think I also threw in a Clavinet with a [Fender] Twin reissue amp and a DI, and a DI’d Rhodes for extra measure, but at that stage we were mainly focusing on bed tracks from the rest of the band,” Dorsey says. “Jon didn’t do any live piano there. We put the Nord and Roland keys through Synthogy Ivory II, through an Apogee Duet, and took MIDI and audio through there.”

The setup was similar at Parlor Studios, though Cleary also played the studio’s rebuilt 100-year-old player piano. At both facilities, Dorsey set the artist up with a Neumann mic for his guide vocals: an 87 in Music Shed and a 47 in The Parlor, where “Dyna-Mite” was captured.

“He wasn’t really going for keepers in either of those cases,” Dorsey explains, “but I always try to set up so if there’s a great pass and he wants to use that, it’s clean enough that we can use it.”

After band tracking, there were still overdubs to tackle. The horn section, as well as background vocals by Ross, Turner and Quiana Lynel, were recorded in FHQ.

“Jon’s studio is quite big,” Dorsey says. “He has an iso room for drums, a big tracking room, and a control room that’s a room-within-a-room, isolated from other parts of the house. I had the brass section in the big room lengthwise, so the sound would throw a little farther. They were miked with KSM44s, but I don’t like to get too close in. There’s a sweet spot I’ve found that works best, especially when you start to compress. I back up anywhere from 6 to 12 inches. If the mic is too close, the SPL will destroy almost any mic capsule.”

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get it delivered right to your inbox.

And then, of course, there were decisions and edits to make before Porter took the tracks to his studio in the UK to mix. “I think many times the more ballad-type songs tended to stay more akin to Jon’s original version, whereas on the more up-tempo numbers where the band stretches out more, things become quite different from the initial concept,” Porter says. “Often Jon thinks my initial mixes sound too big or too shiny, but we usually get to what he likes fairly quickly. He can be very particular, but we’ve done many records together, so each of us knows what the other wants.”