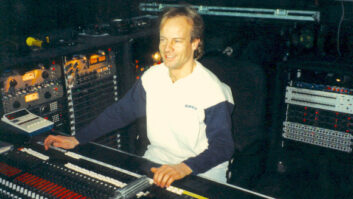

Jimmy Douglass seems too young to have done so much. His past credits include work on sessions with icons such as the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Foreigner, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder and Hall & Oates; groundbreaking records with Slave; and current Platinum projects with Timbaland, Ginuwine, Aaliyah, Lenny Kravitz and Missy “Misdemeanor” Elliott. The explanation? Obviously, when you start off working at Atlantic Records’ New York studios while still in high school you get a jump on the business. And maybe having two personas makes a difference-Douglass is credited on Elliott’s Da Real World as two people: engineer “Senator Jimmy D” and mixer “Jimmy Douglass”-if you’re two people you can get twice as much done in half the time, right?

In person Douglass is a winning combination of very cool and very warm. Although he’s not a native New Yorker, he has spent most of his life there and it shows in his fast-talking, East Coast style. Besides the aforementioned artists, his recording career includes work on pop/electronic projects like The System’s “Don’t Disturb This Groove”; jazz recordings by George Duke, Alfonso Johnson and Stanley Clarke; projects by musical wild cards like Frank Black, Vernon Reid and Willy DeVille; and chart-topping R&B tracks by Jodeci, Jay-Z and SWV.

Mix caught up with Douglass for a series of conversations that took place at his New York recording domicile, Manhattan Center Studios, on breaks from working the night shift on a collaboration between Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit, rapper Jay-Z and producer Timbalaud.

You were literally just a kid when you started in this business.

I started out in high school. I was a musician, and I wanted to be a producer, but I didn’t know what a producer was. I happened to know some people who happened to know some people at Atlantic Records, and it was someone’s good idea that I could work at Atlantic’s studios. The concept was that I could work in the evenings making tape copies-dubs for foreign countries, things like that. Put the tape on, copy the tape, pack it up, and, while the copies were running, I could be doing my homework. It was a good idea on paper, but the part of the building I was working in was two doors down from the main Atlantic Studios where you’d have Aretha recording with Tom Dowd. You’d have Dusty Springfield, the Young Rascals, Cream. So I never did get to do any homework-I’d put the tape on and run down the hall. The length of the tape was half a side, about 20 minutes, so for 20 minutes or a half-hour, I wasn’t there.

Could you sit in on recording sessions?

Oh yeah. This was in the early ’70s, and it was a whole different world. For instance, Tom Dowd didn’t have assistants. It was, you just did what you did, and whoever was there was there.

So you kept working for Atlantic and kept moving up.

Absolutely. I started working with Tom at night, when nobody else was there. I was just kind of watching and trying to figure out what he was doing until it got to where I was able to help him. And to where he insisted that I was probably pretty good at doing other things besides tape copies and that they should move me along the ranks-at least as much as they could with my schooling still going on. Tom also encouraged me to try stuff. Like, I’d drive into the city in the morning before school, take old tapes and put them on the machines, and figure out how to work things. Stuff like that-nobody minded.

Because it was Atlantic’s studio, it wasn’t like the studios were really there to make money. They were there to service Atlantic artists. It was Jerry Wexler, Ahmet Ertegun and Arif Mardin. I was there in this great arena with all those legends who were doing it for the love of music-something you don’t really see that much anymore. And it was a simpler time. They had the power to make decisions. There weren’t as many people who you had to go through to decide if something was all right.

So, what happened was, eventually, I got better, and they started trusting me more, and I started doing more.

It seems much harder now to get started-the field has narrowed.

Well, technology has changed the whole thing, and I have a perspective because I was there then and I’m here now. Back in the late ’70s, people would come to me specifically for what I did. They knew I had a certain talent and I could do things to sound, but they had no clue how I did it. Really, they had no idea. Oh, maybe every once in a while, you’d get a wiseass who’d say, “Why don’t you put some 5k on that?” and you’d look at this guy and say, “Okay, what engineer did you hear that from?” Because they didn’t know what they were talking about-it was just something to say.

But today, somebody with a couple of dollars can go to Sam Ash or Guitar Center-for $3,000 to $10,000 you can have a pretty technically amazing studio. Musicians can play with the buttons and knobs and get a basic flow going and a general idea of how it all works. So now, when a guy comes and sits next to me, I have to look at him and think, “You know, this isn’t magic to him.” I have to look at him a little differently, and my role becomes a little different. I have to respect him more and include him in the process of what I do.

Of course there are still guys who spend the money and don’t know what they’re doing! But I have to have a very open approach to everybody. I believe everybody has something to contribute in this process, hopefully! And I treat them like they do until they prove the other way around.

How do you maintain that open attitude? When you’ve been at it a long time it’s difficult to avoid becoming closed and cynical.

I’ve noticed that gets you nowhere in life. There are so many ideas out there on this planet, and you never know what will work. One thing about me, even when I’m producing a record, I was never one of those people who would have to say, “That was my idea, therefore it’s good.”

I don’t care where the idea comes from. To me, the process of making a record is the best ideas are put forward. Some get thrown out, and some we try even though we know from experience that may not be the way to go. That’s always a hard call. Sometimes you know that you’re going to go a long way to get maybe another five percent; and maybe that’s not what you want to do that day, budget-wise, etc. But every now and then, somebody will jump up and down and say, “This is really important to me,” and I’ll say, “Okay, I’m going to spend this extra three, four hours.” And you know what, sometimes I get 50 percent. That’s the part that you never know, and that’s part of the attitude to being open.

Would you say you have a certain sound?

Definitely. I don’t know if I can describe it, but you can hear it in all my records. It’s solid, and I’ve always liked vocals up front. To me, they sell the song. Some engineers forget that when they make mixes.

I’ve always looked at records like movies: the record producer is the director, and the engineer is a great cinematographer. And I’ve looked at the song as a script, and the instruments I look at basically as sets. I don’t mean I look at it that way all the time, but when I sit back it’s like, that bass is so loud it’s obscuring the vision of the actor. We’ve got to push the set back a bit and tone the color down, that kind of stuff.

You work at Manhattan Center Studios a lot.

Yeah, it happens to be one of those anachronisms in the middle of Manhattan. Growing up in a house studio like Atlantic, I got very used to being able to leave stuff set up, and to have more freedom with scheduling. You go to the big boys, every two minutes, they’re like, “What are you doing tomorrow; what are you doing now; when are you doing this?” At Manhattan Center, they allow us the kind of flexibility to not have to know every exact thing that we’re doing and if we miss a beat they won’t kill us.

They have two great rooms. I work mostly in Studio 4, which has a [Neve] VR. My preference is definitely the Flying Faders system; I think I’ve mastered Flying Faders.

You like to record and mix on the same board.

If I can. If I’m really lucky, I’m able to go from soup to nuts. It makes life a lot easier.

Especially in hip hop, they do a lot of building in the studio, as opposed to thinking about it before they come in. They build the tracks and the ideas and the parts of the song there. It used to be, on a lot of records, people would use their imagination to know that things would be right later, and they didn’t have to hear everything to do their part. But in hip hop, they can’t go on unless everything is there-they can’t create the next idea. So as you’re building, if you’re fortunate enough to be building in automation, when it comes time to mix, the mix really isn’t the greatest deal in the world. We build the sound that they want as we go, and all you have to do is just embellish it a little bit.

You’ve been working with Timbaland a lot the past couple of years. How did you two hook up?

It was a side effect. I was invited to do Jodeci’s last album by this studio upstate. I had done some work for them previously-kind of bailed them out on a three-day marathon where people came up, about five acts and three sets of producers. I did all the sessions, and they were kind of impressed with me. So when Jodeci booked in and they didn’t really have an engineer, the studio called me. The side effect was that Timbaland was in the crew with Missy, Ginuwine, Playa-they were all just kind of up there. I took a liking to Timbaland and what he was doing. It was very innovative and different, and he was very free-free of worry about where it was going. So, there were two studios, and he and I ended up spending most of our nights after Jodeci was done just working on more stuff.

Do you two rent a lot of gear or are you self-contained?

Between my outboard EQ and effects and everything, his equipment, and MIDI equipment that we share, we have six to eight roadcases, and wherever we go we set up shop. All we need is a VR.

What is the main composing tool when you’re working together?

He uses various sequencers-he uses the Ensoniq ASR a lot, and I have an array of MIDI sound modules.

What are some pieces in your rack?

I use an Akai S3000 for vocal flying-that’s my sequencer-and of course I have the ASR10X, which I like for the effects and the resampling ability. All the sync boxes are mine. That’s my area-I’m Mr. Sync Man.

How do you lock everything up?

We’ll stripe some SMPTE. I steal whatever tempos he’s dealing with, and I become the master tempo man, and I let all the sequencers slave to mine. Everything slaves to my SMPTE, to my master sync box.

Is a Lynx the main sync box?

Yes, actually, I’m still in the old days. I bring my own two Lynxes wherever I go because some studios don’t have them. They have these new things that they need for video capability. But the Lynxes are so simple. I don’t need the video stuff. I just need to simply offset things.

So was Da Real World written all in the studio?

Missy could be one of the fastest writers that I’ve ever worked with, and Timbaland is one of the fastest track/beatmakers. Between the two of them, they can do a song in half an hour.

So they come in with just an idea?

[Laughs] They’ll just come in.

Okay, then they’re laying parts down and you’re bringing feeds up on the console and making it sound the way you all think it should…

Temporarily. Then she’ll write a song around it, and then we’ll go back and rethink the track and then redo it, and she’ll rethink it. It’s a give and take. “Oh, you did that. Well, I’m gonna do this! Oh, you did this. I’m gonna do that!”

So, first the crew will be just composing and you’re getting sounds, and after a while, you roll the tape and record some sort of basic track.

Yeah, like a “glop track,” I call it. There it is, a glop of it, so something can be written around it. Then I do the vocals.

There are a lot of vocal tracks. How do you combine parts?

I try when I can to keep them totally spread. I try not to comp them. I’ve found that leaving all those doubles and quadruples open instead of just comping them and making them one stereo pair gives me this amazing ability to have extra space when I’m mixing. It’s a track killer, but when I can have it, it makes things a lot easier.

What mic do you use on Missy?

Usually an 87-mostly for consistency because I end up recording her so many different places and because she does things so on the spur of the moment. She doesn’t have the time to wait for some special setup. Really, she’s very quick; when her mind is moving, it’s moving, and all you have to do is capture it. She’ll switch three songs on you in two seconds, and she’ll want to punch in. This way I can always find my way back to where it was.

So you probably don’t EQ much to tape.

I try not to EQ-except, of course, for those telephone voices she does. I do those right to tape. She insists on hearing it that way then and there. She can’t get the vibe if it isn’t that way.

What format do you record to?

I like to do the tracks analog, and when we can afford it or I’m in a place where it’s available, I do the vocals digital on the 3348. I also have a DA-88 set up that I use for flying vocals if I don’t have the luxury of the 48. If I just want to fly eight tracks of the vocals and use them for the hook or something, it helps to keep the autonomy of the tracks and still fly them.

You’re not recording to hard disk?

I sometimes use the hard disk stuff to fly parts around. I usually have Pro Tools sitting in the room that I lock up when I need to. I’ll just fly to the Pro Tools and fly back. I do that a lot, especially to create the clean versions that we have to do a lot of these days-to get the curse words out or flip them around or whatever.

Personality-wise you’re an interesting combination of speedy and relaxed. Even though a lot of the people you work with can be very fast about writing, there still must be hours of working out parts where there’s not so much to do and you have to just kick back and let things happen.

Absolutely. That’s part of the phenomenon of the way R&B and rap is often done these days. A few years ago, I had some training in this area. I started working with some people, and they’d say, “Tomorrow at one o’clock.” I’d come at one and nobody would be there, and nobody would do anything for three, four, six hours. And after a while, I’d start saying, “Hey, this is ridiculous, let’s get moving!” And they’d go, “Jimmy, just chill.” And we wouldn’t get rolling till seven, eight, nine and get out at three or four in the morning. But after a while I realized nobody was in a hurry but me! So it was calm down, just relax and let it happen because it is what it is, and that’s the only way it’s going to happen,

What do you do for those hours in the hang?

Take care of whatever business you can. You do whatever writing you need to do-I have a little sequencer set up and a couple of modules, so sometimes I’ll be writing. And of course, you get to really learn your equipment! That’s one way I got to learn the VR so well. I was sitting there many, many days, and I’d read the manual over and over. I found stuff that people didn’t realize was in there.

What are some of your strengths?

I really enjoy depth in records, space in records. Even when it’s crowded, there’s still a way to get space in there somehow.

What do you do to create that depth?

One of the things I try to do is to look at left, right and center and not to get too hung up on places in between. It’s something Tom Dowd told me years ago: “There’s a left, a right and a center-the rest of it is all crap.” [Laughs] So I try to work with that instead of spending time putting things in every little space across the spectrum. And I try to create depth by putting delays that send stuff back into the speakers, making it more concave from my perspective instead of left and right.

The quiet parts of your tracks are really quiet. How do you achieve that dynamic range, hot levels?

Yeah, I’m a squasher. Everything is slamming. I record at plus nine, and I hit the tape really hard. It’s a holdover from my rock ‘n’ roll days-I like the sound of it. And I try to punch in only when I need to. I don’t leave mics open and tracks in record. That’s probably a big part of it, too.

How long does it take you to mix a track?

If I’m lucky enough to be doing soup to nuts, I’ve already been mixing as we’ve been going along so all I basically have to do is recall from where I left off. That’s a method Tim and I developed in Rochester, because we were doing so many songs every night for so many different people. He’d have to take ’em up and put ’em back, take ’em up and put ’em back, and I had no assistant! So one of the things I learned how to do was to minimize my effects because to document them all by myself and then to change the tape over was a bit overwhelming.

And, living in the same room a lot, I was able to have everything always lined up the same way, so I developed a method of storing the recall right in the actual mix, without a big deal.

So you don’t have to try a lot of things in the mix.

No. I sit and play with the vocals and really get them nice and put effects on them and work on the spatial differences and the spread. Then we do the drops.

You mean like cuts, muting parts and creating arrangements.

Right.

You’ve had ups and downs in your career-have you developed some kind of general philosophy about the business?

I really believe if you’re any good at this, you’re going to continue to be good at it. It’s not about the million dollars you might make today because, in my experience, the money has always come after the love. If you’re really digging what you’re doing and you really put your heart into it and you are doing the best job you can, you may not have that hit today, but eventually you are going to have that hit, and the money will come. Maybe I’m a bit of a romantic about that.

We don’t always hit a home run. There are albums I made with people that didn’t happen, but we made a really fine, quality product. They didn’t sell like they should have, for whatever reason, the record company, the management, yada. But the point is these people I worked with I know for life, and I love them for life because we experienced something together, a creative bonding that’s irreplaceable. And that’s as important to me as the successes I’ve had.

Aretha FranklinYoung, Gifted & Black engineer

The Rolling StonesLove You Live, (1977) remixer

Foreigner, Records(1982) engineer

Atlantic Rhythm & Blues 1947-1974(1991) digital transfer mastering engineer

Cassandra WilsonBlue Light ‘Til Dawn(1993) engineer/mixer

Stanley TurrentineIf I Could, (1993) engineer

Jodeci, Show, The After Party, The Hotel, (1995) engineer/mixer

Roxy MusicThrill of It All(1995) engineer

GinuwineThe Bachelor(1996) engineer/mixer100% Ginuwine(1999) engineer/mixer

Aaliyah, One in a Million(1996) engineer/mixerAre You That Somebody?(1998) engineer/mixer

Jay-Z, Vol. 2: Hard Knock Life(1998) engineer/mixer

TimbalandTimbaland and Magoo(1998) mixer

Playa, Cheers 2 U(1998) engineer/mixer

Missy ElliottSupa Dupa Fly(1997) engineer/mixerDa Real World(1999) engineer/mixer