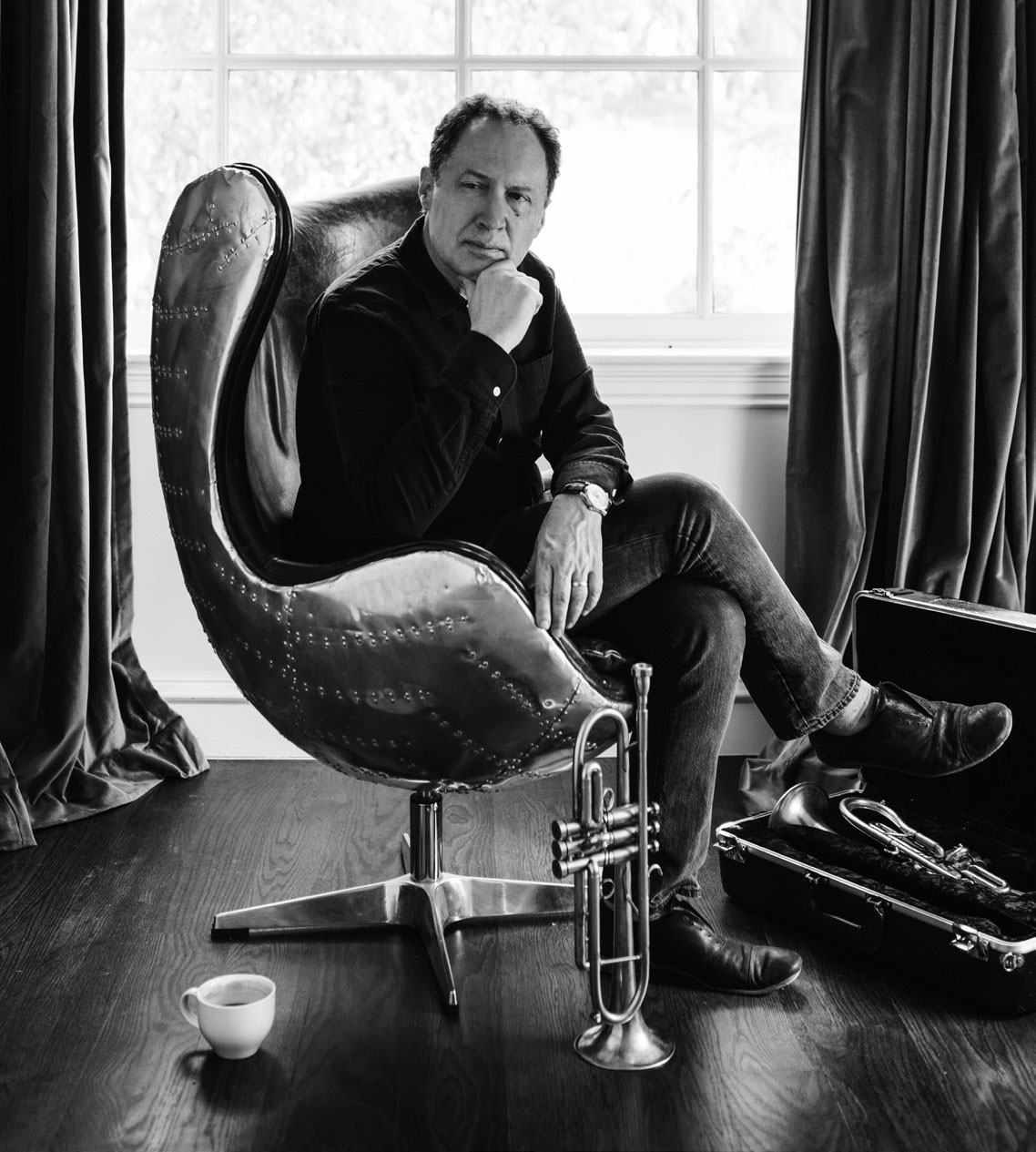

There are few artists who move as fluidly between the worlds of film, television, recording and performance as Mark Isham. As a composer, he has scored dozens of highly acclaimed films, both big-budget and small, and long-running primetime dramas. As a musician, he’s won a Grammy for the eponymous Mark Isham and been nominated twice more. As an artist, he’s recorded and performed with both the pop and jazz greats of our generation and the up-and-comers on the fringes of ambient and electronic music. These worlds are comfortably reflected in his studio setup, where a Euphonix CS3000 film console faces a smaller music console, amid an array of analog synths and rotating, varied instruments, depending on the day’s project. He toggles between the two by swiveling in his chair. On the one side he listens through a series of monitors built by film score mixer Dan Wallin, along with a set of his trusted Tannoy Golds; on the writing side, he has Dynaudio near-fields as he gets up close.

When Mix last talked to Isham in 2012, he was entering his second season of the hit TV show Once Upon a Time and working on American Crime. Since then he has released a couple of albums, the most recent EP, coverART, last November. He has performed on tour and at festivals throughout the States and Europe, often in collaborations. He has picked up a new TV show from Marvel and ABC called Cloak and Dagger, having done the demo for the pilot. And last year he wrapped the score on his first full-length animated feature, Duck Duck Goose, which seemed to inspire and invigorate him.

The talent and the techniques of film and television production are merging. Last September this was the focus of our annual Sound for Film & Television event at Sony, where Isham was a featured speaker.

Your studio setup remains the same? Still with the Euphonix console?

The console is so flexible we just stayed with it: 64 mic pre’s, it all sounds really good. Six inputs on every line. It’s hard to beat it for what I do. Completely resettable. Fortunately the guy who built it up for me in the beginning built a comprehensive patchbay and I haven’t had to do much to it.

Also, over the years I’ve collected vintage and new analog synthesizers. I’ve been building up to how to get these guys into the film world. They are great for the way they let you compose, but then how do you bring that into the world of the DAW? That is the technological challenge I’ve been working on. You can challenge the equipment, but it has to be seamless. The minute something doesn’t work, that creative idea gets smashed.

I still write in Logic, with a pretty big Universal Audio UAD system behind it, which gives me all that classy compression and ambience. It’s that whole second layer that allows those demos to kick ass. I still mix all of my own demos; that process is crucial to me. Partially it’s that these are pieces I’ve just written, so nobody will get there faster than me. I’ve been fanatical about mixing since I first went into a recording studio.

Do you listen for different things when mixing for film vs. television vs. music?

Not necessarily in the music, per se. The great thing about my main writing space, my studio, is that I have everything set up in one room. I have a writing console set up in one direction, and then I have a mixing console facing it. Dan Wallin, the fantastic film scoring engineer, designed a series of monitors more than a decade ago. Somebody brought them over a few years ago and they’ve never left the top of the console. They are just so right for film composing. You can wander around the room and hear how it behaves as if you’re in a theater environment. There’s no sweet spot in that sense, and yet the image is really, really good. For film music, I have a bunch of those.

For the writing side, then, I use Dynaudios, a little more near-field and a little more modern. In the writing, I’m bent into the screen, up close, and I need something clean and clear and not fatiguing. They’ve worked really well for me. And the footprint is smaller. I like my writing setups more compact. I find this to be the most creative and productive setup for how I work. I turn my chair around and it’s like I’m in another room.

What’s going on in television? What brought you back?

It’s pretty exciting actually. A lot of the really good writing has moved into television. The polarity between the big committee-driven blockbuster project and the $5 million-dollar independent film is greater than I’ve ever seen it. That sort of middle-ground movie—very few exist any more. And television beckons. With Amazon and Netflix and others willing to be edgy, willing to take a risk, it’s pretty exciting.

Still, television has been a learning experience. You do have to make decisions, and I like that. You can’t really fool around and try stuff out. That’s why I try to keep my plate equally full with film work, where you can sit with a director and develop ideas over months. In television, that first decision out of the box has to be made. That’s why I insist that in the first part of the process I limit myself. I will only sort through the infinite of choices for a very short time. [Laughs]

A lot of times I’ll just play a note, against picture, and think, Does this note, or this sound belong in that world? Take a big scene or a small scene and play around with textures. Play around with temp music, to see if a style fits. A funk groove, does that fit? That’s my first decision: Let’s limit this. Then the limits can inspire you to be creative.

What are you up to now?

Well, I just finished my first real animated feature and I really enjoyed it. It’s called Duck Duck Goose. It’s not a Disney style in that it’s not a musical. But the music has to attach to the storytelling very directly. Every nuance has to reflect itself in the music. I didn’t want to get too slapstick or too on-the-nose about it, but you have to pay attention to the fact that it’s an animated picture and take a slightly different approach. That was a nice balancing act for me.

Then in the last year, I just decided that it’s very lonely sitting in this room. [Laughs] So I’m doing some interesting collaborations right now. I had done some work with Moby a few years ago, so he and I are collaborating on something coming up, which is fun. He’s a real character. An unbelievable talent.

I’m also working on a project with BT. He and I had met a couple of times, and we hit it off—first off, through our obsession with gear. That’s fun to get to know him.

Then I’m working with a young woman named Caroline Polachek, who was half of this band called Chairlift, which had a run of 10 or 12 years. She’s doing her first solo record, and I’m writing with her. It been has been a real turn for me and really inspiring. And believe it or not I did a track with Joe Perry. From one end of the spectrum to the other.

I just love the whole process of making music. I love it. But I also need to keep some sort of goal that is constantly moving ahead of me. It’s fine to have a new Marvel show, and a new animated picture. But it’s also sometimes just damn lonely. I’ve found some of these collaborative projects inspiring because you get to interact with another point of view. You challenge yourself to do thing you wouldn’t have done before.