For most people, being an assistant engineer on The Beatles’ Abbey Road would be the high point of their careers. For a 19-year-old Alan Parsons, however, it was just the beginning.

Within a few years, he had recorded Pink Floyd’s legendary The Dark Side of the Moon, worked with acts like Cat Stevens, Ambrosia and The Hollies, and then embarked on his own notable recording career with The Alan Parsons Project, which had numerous hits like “Eye In The Sky” and “Don’t Answer Me.” Still active in the studio to this day, in recent years, Parsons produced Jake Shimabukuro’s 2012 album, Grand Ukulele, and engineered Steven Wilson’s 2013 release, The Raven that Refused to Sing (And Other Stories).

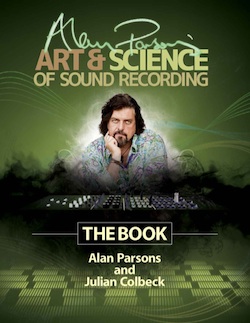

When he hasn’t been mixing at one desk, however, he’s been typing at another, co-writing The Art and Science of Sound Recording, an in-depth book on the entire music production process. Based on his 10-hour DVD/online series of the same name, the book covers everything from a brief history of recording to how to survive a studio disaster.

Sitting down with Parsons and his co-author, Julian Colbeck, at the 137th AES Convention provided a chance to discuss all this and more. What follows is a condensed version of the wide-ranging discussion over tea, just an hour after Parsons’ Keynote Address.

PSN: Your book shares a career’s worth of knowledge, but what made you start that journey? What made you want to get into recording?

ALAN: Hearing Sgt. Pepper for the first time.

PSN: And then within a year or two, there you are, working for the people who made it.

ALAN: Yeah, exactly—in fact the White Album came out the week I started at Abbey Road.

PSN: That has to have been an incredible learning experience—a heck of a foundation to build on, education-wise. Anything you took away from then that influenced you later?

ALAN: Oh, yeah—every moment was an influence, I would say. I think possibly I try to model myself on George Martin. He was a great, great mentor—the Beatles had total respect for him and he was musical enough to be able to translate what they couldn’t themselves translate into dots and rests and bar lines and stuff; he would fill in that gap for them. He’s great [and the experience was] a great asset to me.

If you asked Geoff Emerick the same question, he would feel differently; he’s much more the sharp end of what the Beatles wanted and what George Martin wanted. Just watching them [all] together, I thought they were magic. Magically compatible with each other. And [George Martin] was rightly called the Fifth Beatle, I think. The Beatles, of course, were the greatest songwriters, the greatest rock band that ever lived—so how could it not have been an experience?

You also learn how not to do things though, too. I thought, for example, George Harrison spent too long doing guitar solos, whereas he could have learned a part at home and then come in and done it [snaps fingers] just like that. But because Beatles budgets were totally unlimited, he could work on it at Abbey Road.

PSN: Certainly you got proper training at Abbey Road. Today, most of the large studios are gone, and learning on the job as you start out doesn’t happen anymore, for the most part.

ALAN: I had three or four after the speech today asking, “Can I be your intern?”

JULIAN: I think people miss that kind of community.

ALAN: I was reminded by my friend, the manager of Capitol Studios for a long time, there used to be an apprenticeship system. You would start making tea and coffee, you would watch your mentors at work, learn from them and you would see what one engineer did that was right in your eyes and what they did that was wrong in your eyes. You learned to have your own style—and that’s gone; it’s so sad. In a way, I’d say the video and the book are at least an attempt to try and show people what I did, what I do and how I got there.

JULIAN: I think that music-making and recording has become such a lonely sport. Nowadays you can be your own artist, producer and engineer all in one, in this laptop environment. And as Alan was saying, the apprenticeship process not being where it was, I think one of the things that we did in the DVD and the book was to involve lots of other people as well as Alan—it’s not just one voice. Alan interviewed many different people, so as he said, you see different approaches.

PSN: You’ve held Master Classes in studios, and the DVD has been out for a while so you’ve gotten feedback on it—are there any particular topics where, when you start talking about them, you suddenly see that moment of enlightenment where people suddenly “get it?”

ALAN: People are often surprised when I tell them I don’t use compression on mixes, saying, “How can you mix without compression?” So sometimes, yeah, I’ve seen sudden enlightenment when they just watch me mix: All he’s doing is balancing! But that’s all recording really is—the art of balance—and some people think that in order to be good, you’ve got to use every effect and every piece of equipment at your disposal…but you don’t have to.

PSN: The lost art of restraint—and yet you had 16 tracks for recording Dark Side of the Moon, and some people would find that alone to be restraining now. Was 16 tracks a limitation or did it help focus perhaps? Is it possible to have too many options now?

ALAN: I think it’s very time-consuming to have those options now. The mark of a good producer is to be decisive—and that’s what we had to be. I think if Dark Side was remade today, it would take forever…forever and a day! I’ve always been a believer that whatever equipment I have, I can make it work to my best advantage. Take what you’ve got, make it work.

PSN: With that in mind, what level is the book aimed at—beginner, intermediate…?

JULIAN: Some people who have grown up in a DAW-based world don’t realize where the equipment that is now available as a plug-in came from—what it was, what it did, why you’re using it. We lift the lid on that for them in the book, because they’ve got the tools now on a laptop and they can seemingly make a record with all the stuff in place, but because they don’t understand the genesis of those tools, they don’t understand maybe how they should be used, or why or when or indeed if.

PSN: It’s just another set of buttons.

JULIAN: Exactly, and what Alan does so well is to remind people or tell people for the first time about these things. If I can tell a quick story, we had a great moment when we did one of these Master Class Training Sessions, where Alan was EQ’ing the overheads. He went to the left-hand side and EQ’ed that to his liking. and then went to EQ the right-hand side, and someone said, “Well, why didn’t you copy that across to the right?” And Alan said, “Because it sounds OK.”

ALAN: People just think “OK, left and right should be equal; the parameters, the values should be the same.”

JULIAN: Not necessarily so.

ALAN: Not at all, you know, and you’ve got to listen to it.

JULIAN: And it was shocking to them that Alan was actually doing something twice. It seemed needless, but it wasn’t. That brought home to me why people need this material because otherwise, you’re just doing what seems to be the logical thing—except that it’s not. It might seem the logical thing, but it’s not the musical thing. So that’s who will benefit from this.

ALAN: The book, we’d like to think it’s for everybody; I mean, even somebody who’s been doing it as long as I have should get something out of it. It’s great for the person who’s genuinely interested in the mysteries of recording.