This summer I was tapped to teach a Sound for Picture course, which provided an opportunity for me to not only review the range of skills involved in modern production—music scoring, sound effects, dialog recording, Foley and so forth—but also to reflect on what a young person going into the profession can expect in the future.

Of course, in the age of the freelancer, job security isn’t at the level it once was in our industry; that merely reflects the insecurities felt in nearly every other career in the U.S. But for the audio pro hungry for work and hustling for gigs, there are so many different job opportunities and such a variety of media that, with persistence and a broad skill set, he or she can keep busy and in a positive cash flow.

Of the utmost importance is the ability to find creative satisfaction in problem solving, because that is where much of the inspiration is needed day to day. Especially mid-production when the routine sets in and the end is nowhere in sight. Consequently, much of the homework in this course is meant to introduce the students to this glamorous level of tedium. Moreover, they learn that, to be successful, they must be speedy, detail oriented and accurate with their work, as many clients will expect them to be fast and good from the get-go, not to mention affordable. Tell a prospective client to pick only two of those three, and they’ll likely pick someone else for the gig. (Although, sometimes that’s okay!)

More than simply teaching a particular set of production skills, however, my intention in this class is to point students toward the potential of their craft while retaining the humility required in the field: They should look for unexplored territory within the media they are working rather than rely on clichés (though they should know the clichés in case they are asked for); humility, because their work should be felt rather than noticed—that’s the sweet spot to aim for.

Of course, the work must conform to the whims of the director, producer, studio exec or whoever else signs off on things. That means that either the audio folks have to be good at selling their innovative ideas or the decision makers have to be open minded, interested in stretching the boundaries, and willing to take risks—a lot to ask, but it does happen.

We begin by analyzing musical scores to see how they influence (or are influenced by) other elements in the production. Like the major-motion-picture business itself, modern soundtracks seem to be in a recursive spiral: Just as we see more and more remakes and sequels, we hear a distillation of iconic film scores, often because of how directors and producers fall in love with temp tracks built from previous works.

In fact, I’m always amazed at how much power the person assembling the temp score (often the picture editor) has but how little recognition he or she gets: Their adept choice of tracks, which defines the mood of each scene during the early stages of production, can influence the decision makers more then the latter will admit, and force the hand of composers more than they wish. For example, wouldn’t it be nice if someone would compose a new motif for spy-related scenes so we can stop referencing the original James Bond or Mission Impossible themes?

While feature film scoring is far out of reach for the nascent sound artist at this point, it’s important for them to begin forming a personal aesthetic about the impact of sound and music. The big eye opener, of course, is experiencing Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. What I’ve found is that simply dropping in on a scene or two and explaining how the tension is created solely by diegetic sounds—bird sounds both natural and electrically generated by the Mixtur-Trautonium—doesn’t really get the point across. Rather, it’s more effective to watch the entire film, with the instruction to focus on the overall sound, and then ask the viewers what they noticed. This is where the lack of traditional mood-setting music cues and the importance of sound design really hits home.

The Birds provides a classic a case where the innovative aspects of the sound track are remarkably subtle for the average viewer, which, again, is what makes it successful. Unfortunately, the chance to work on a production where such innovations are encouraged is still remarkably rare, especially considering the huge variety of media being produced now compared to half a century ago.

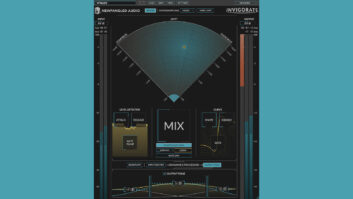

What will define a successful career in the future for those interested in creating sound for media is not only having something to say with their work, but, as usual, providing something that no one else offers. If you think your competition is tough now (e.g., directors who think they are film composers because they have a copy of Propellerhead Reason or Ableton Live on their laptop), wait until you hear the next generation of algorithmically based media-scoring tools. It’s likely they’ll do for composers and sound designers what drum machines have done for drummers.