There’s a reason that backstage crews around the world wear black, or at least dark colors, and it has everything to do with not being seen. The stage hands, guitar techs, monitor engineers, P.A. riggers, LDs and lighting assistants, video operators, wireless wranglers, pyrotechnics specialists, cable runners, drum tuners, A2s, systems engineers, FOH mixers, even the guy with a camera crawling along the catwalk a few feet below the roof of the arena—once the lights go down, they disappear.

They may have spent the last six months on the road, in town after town, working 14-hour days on the floor with the lights on and a small army of techs hustling to build that stage, hang the P.A. or set up the lights, but after the dinner break, it’s back to the shadows, as the job requires and, I’m sure, as most of them prefer.

There is a fundamental difference in the human psyche between those who have a burning desire to be up on stage in front of 20,000 people, screaming into a microphone and wailing on guitar, and those who would much rather work behind the scenes to make that happen. On a good night, when everything is clicking and the show has a hint of magic, both artist and crew feel the joy. The team played a great game and they won!

On January 30 at the Kia Forum and Intuit Dome in Los Angeles, at FireAid, the team played a spectacular game.

More than 30 artists showed up to perform, adding an extra date to their Grammy Week schedule. None of them worried about their slot in the sixhour show, and many of them went raw acoustic, with no glitzy backdrops, backup singers or playback tracks. Egos were put aside. They were all there to raise money—a lot of money it turns out—to benefit those affected by the fires that had raged through Los Angeles less than three weeks prior. It is a good story, one that represents the music community at its finest. It turns out that there’s an equally good story behind the scenes, with the crews that made it all happen.

As my Mix colleagues Clive Young and Steve Harvey detail in this month’s cover story, it’s not a simple thing to put together a six-hour, 30-artist, two-venue live and streaming music extravaganza. Typically, the producers would have months to prepare, with extensive dress rehearsals to fine-tune the mix, choreograph camera moves, practice set changes and work out timing down to the second. For FireAid, they had less than two weeks to build the whole thing from scratch, and with much of the L.A. production community already booked for Grammy Week, they had to pull in more than half the crew from across the country. Everybody responded.

The Feat Of FireAid, Part 1: Rocking The House

The Feat Of FireAid, Part 2: Streaming To The World

Scott Pederson, president of Remote Production Group, brought in his two-studio Gemini truck, where Bob Clearmountain mixed music live to streaming from the Forum, and then arranged support from the TNDV truck out of Nashville, with Biff Dawes mixing from the Intuit Dome.

Firehouse Productions out of Red Hook, N.Y., led the audio effort inside the venues, with support from Clair Global’s ATK Audiotek and Eighth Day Sound; d&b audiotechnik donated a KSL P.A. for the Forum. As Firehouse VP Mark Dittmar says in the story: “Every aspect of a show that you would normally spend two to three months working on, you had to spin up in under a week. Everyone dove in. It was impressive to watch a bunch of pros come together and cut loose, doing what they do best—not working with a lot of paperwork, just with, ‘Hey, let’s get this done.’”

The show must go on. Downbeat at 7. That’s what drives a crew.

I’ll leave you with a small anecdote that illustrates my feelings about the importance of a good crew, and my respect for them every time I see a show.

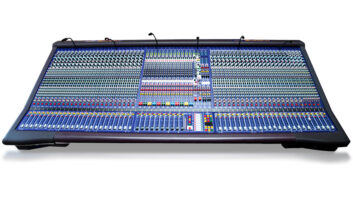

When my daughter Jesse was in the 5th grade at Thornhill Elementary in Oakland, one of the mothers, who had a background in theater, wrote a short musical play based on Aesop’s Fables. She was the director, and another mom played piano, but other than that, it was all put on by the kids. I was elected to be the “tech parent.” Jesse was at the lighting board, with another two kids on spotlights, A 10-year-old boy was at an 8-channel Mackie, and we had a young girl as stage manager.

I thought, “What can I do to make these kids feel special?” So I had my art director make All Access laminates with the show’s title and artwork, I went down the street to Clear-Com and they kindly loaned me six headsets, and at the final dress rehearsal, I told them all to wear black on opening night.

At the premiere, at least three young actors missed their cues because they were backstage playing with the Push-to-Talk so they could say hi to Jesse or to their friend on the spot. Kids in the audience were huddled around the audio board, asking if they could put on the headset and flip up the microphone. Suddenly they were the stars.

At the end of the night, I gathered them all together in a circle. We put our hands in the middle and chanted, “Crew is cool! Crew is cool! Crew is cool!” True story, and I’ve felt that way ever since.

—Tom Kenny.