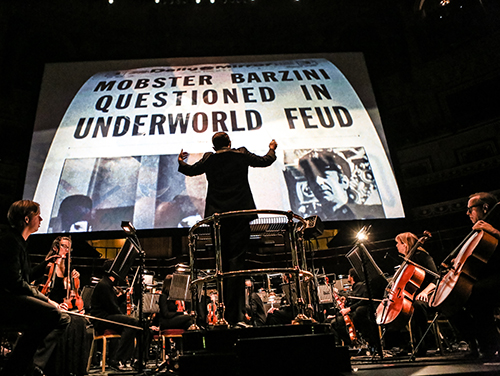

Seeing Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia classic, The Godfather, on a big screen is special. But seeing it with Nino Rota’s unforgettable score performed live by an orchestra is an offer one should never refuse.

Performing live to picture is not simply a matter of throwing the image up onscreen and hoping the musicians can stay in time and sound like they’re part of the movie. “The most common comment we get is, ‘I forgot there was a live orchestra there, I was having such a movie experience,’” says mixer David Hoffis, who handles sound engineering duties for CineConcerts, which produced a recent performance of the semi-touring show at L.A.’s Nokia Theatre.

“The problem is, that’s sometimes said as a compliment and sometimes not,” he continues. “About 80-percent of the audience is really there to see the orchestra, because they’re symphony-goers. They want to hear the music of The Godfather. And the moviegoers want to hear the dialog. So it’s a fine balance we have to strike, to find a middle of the road where everybody’s happy.”

Dialog, of course, is key to telling a story in film, so the dialog track in a concert hall environment has to be handled with care. CineConcerts was provided separate remixed stereo dialog and stereo effects tracks from Paramount, taken from the studio’s 2008 reissue, The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration. Still, there was work to be done to allow those elements to be used effectively with a live orchestra.

“Those tracks were mixed to be heard in a movie theater, which, in a sense, is like a great big recording studio, with proper acoustics and surround sound,” Hoffis explains. “That’s the exact opposite of the ideal symphony concert hall.”

As in any soundtrack mix, the dialog track had received appropriate reverb and other spatial effects to properly place it within the environment of each scene in the film. “But if you add that reverb to the acoustics of a concert hall, your dialog’s going to be floating up in the rafters someplace,” Hoffis explains. “That’s the big challenge for our CineConcert projects, to get the dialog under control—taking something that was meant for an acoustically designed movie theater and putting it in a super-live concert hall.”

To bring the tracks back to a more raw form, Hoffis collaborated with friend and dialog editor Robert Langley, using iZotope RX4 Pro to remove just enough reverb from the tracks to make them distinct in the acoustically live environment. He then applied bandwidth compression to spots where unwanted sounds appeared on the production track, in order to reduce their visibility within the dialog. “There are scenes in the dialog tracks when you can hear actors adjusting their clothing or moving props louder than you can hear them talk,” Hoffis says. “So I try to go in with bandwidth compression and pull down those specific frequencies a little bit.”

For synching, Hoffis and conductor/CineConcerts producer Justin Freer work with video director Ed Kalnins, using Figure 53’s Streamers and QLab live show control software, placing streamers and other indicators as directed by Freer for key points in the score—much as one might have used Auricle in the past during a score recording. “Every conductor is different and uses different color markers in different ways,” Hoffis explains.

For example, when an orchestra is playing at a wedding party outside Don Corleone’s mansion, the camera follows characters inside to continue a conversation that is taking place in his study. “If you’re outside, in the perspective of being near the orchestra, Justin will play the orchestra louder. And then he’ll use a streamer to tell him he’s about to go inside, and he will mute the orchestra to match what would be heard if you were inside the study. So, rather than me mixing that, he controls the dynamics of the orchestra. That way, the audience is hearing the scored music the very same way that they would hear that cue if they were watching the film in a theater.”

Vocal soloists, such as a singer at the party, come on the tracks provided by the studio, and are sent (as is all of Hoffis’s mix) to a powered monitor situated to Freer’s right onstage. “Justin has that cue in his monitor, as reference. He then conducts the orchestra in time with the singer. There’s no click track,” the engineer explains.

With only a two-and-a-half hour rehearsal period, there’s not a lot of time for Hoffis to nail down the mix to the liking of everyone in the audience—both the filmgoers and the symphony-goers. “It’s a challenge. It’s mixing on the fly,” he says. “It’s a live performance, so you can never have total control of the orchestra. Occasionally the orchestra will overpower the movie, and occasionally the movie will overpower the orchestra. But hopefully we provide something both segments of our audience can really enjoy. It’s quite unique.”