“Once, not long ago, a group of musicians came to Israel from Egypt; you probably didn’t hear about it, it wasn’t very important.”

So begins The Band’s Visit, the unusually quiet, intimate Broadway musical that’s made an outsized impact on audiences and critics.

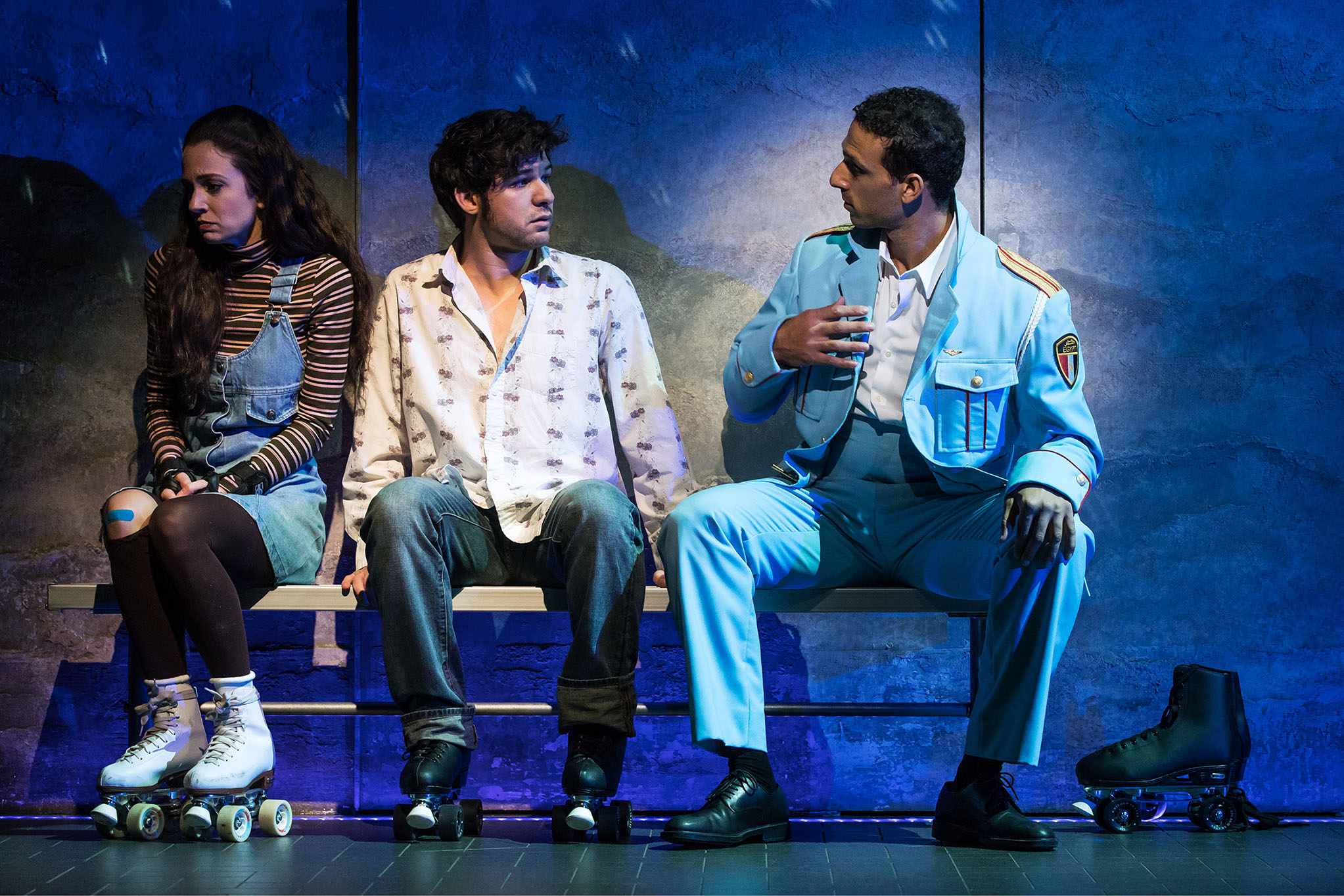

When the Alexandria Ceremonial Police Orchestra is scheduled to play at an Arab cultural center in Israel, they land a day early in the wrong town. They’re stuck in a dull desert outpost until morning, with no hotels and barely a place to eat.

The eight musicians dutifully carry their instruments while dressed in stiff military—yet, oddly, powder-blue—uniforms. They stand out like strange, artsy martinets among the bored Israelis and drab surroundings.

The lonely owner of a tiny cafe, Dina (Katrina Lenk), offers them modest food, bare-bones lodging and, later, a private tour of the desolate town for their older, taciturn leader, Tewfiq (Tony Shalhoub, the star of Monk).

Her real intention is to have a date, and more, with this interesting stranger.

Loneliness and unfulfilled longing are the bittersweet themes of this show, which has critics gushing (“ravishing,” “shimmering”) and ticket buyers lodging it amid Broadway’s Top Ten (grossing around $1 million weekly).

For sound designer Kai Harada (Fun Home), the challenge was not primarily in the show’s uncommon intimacy and quiet nature, which he says he loves and is what drew him to the piece.

Related: Fun Home on Broadway: Intimacy in the Round, by Eric Rudolph, Mix, Sep. 25, 2015

Rather, there are several distinct sets of performers that had to be combined into a natural, yet compelling, soundstage so that the show’s “gentle spirit” could spring to life in a 1,100-seat theater.

Those performers include the 14 actors, one of whom actually plays violin onstage; the show’s unseen orchestra, which comprises five musicians in a room under the stage; and four onstage musicians in full costume, as members of the fictional band. As the show unfolds and the desert night falls, the four onstage musicians play onstage seductively. (These costumed musicians also sometimes recede, joining the orchestra under-stage.)

Harada melded these disparate sources into a cohesive whole using advanced equipment and processing, along with “lots of speakers in lots of places, to create a deceptively natural, coherent soundstage,” he says. “It was so important for me not to get in the way of composer David Yazbek’s beautiful music. It had to sound right.”

To do so, Harada’s system design provides general location placement (sourcing) for the sound of the under-stage orchestra, and much more precise placement for the onstage musicians.

“My first goal was an overall blend of the under-stage orchestra, using a slew of Meyer Sound loudspeakers hung in and around the stage. I didn’t want anyone close to the stage to be drawn to a specific speaker when hearing the orchestra. It just needed to sound like it was coming from the same [onstage] world.”

Contrasting with this generalized sourcing, precise sourcing was used for the onstage musicians who are actually playing.

Aiding in that localization is a newer piece of equipment, the SARA II Rendering Engine from Astro Spatial Audio. “This box helps image acoustic sources, so the listener perceives the cello sound as coming from the cello,” Harada notes. “And for key emotional moments, it can readily create a larger sonic environment, through subtle acoustic enhancement.”

Related: Meyer Sound Is System of Choice for 2015 Tony Awards’ Best Musical and Best Play, Mix, July 20, 2015

The physical locations of all the speakers are programmed into the SARA processor, and acoustic sources—the musicians—are placed in a virtual map of the theater. The system then performs all the delay and level calculations to route each sound source in the proper proportions to the loudspeaker close to that source, Harada explains.

The aim of all of this sophisticated tech is a natural, transparent soundstage, to meld the sound with the storytelling. Harada says that is always his goal.

“What degrades an audience’s experience is sound from a speaker that doesn’t correlate to what they see onstage,” he notes. (Broadway sound designers have long joked that the ideal place for a speaker is on an actor’s chest.)

There is indeed a deceptively naturalistic, almost un-amplified feel to the show, especially in the dialogue between the two leads. “It is about human connection, complete with the silences that come with it, and we kept it natural and intimate,” Harada says. “The creative team felt that the audience might connect better to that energy if they’re not force-fed all the words.”

Paradoxically, the SARA system also helps make the medium-sized Ethel Barrymore Theater seem larger at times. “The Barrymore is a play house, and its smaller size lends itself to the intimacy,” Harada explains. “But there were key moments where it was emotionally appropriate to expand the theater a bit.

“So we placed mics around the proscenium and fed them into SARA’s convolution reverb engine, which is specifically dedicated to room acoustic simulations,” he continues. “Feeding the output of that reverb to most of the speakers, we increased the reverberation time, changing the audience’s perception of the theater’s size. It’s a subtle effect, but I think it works well.”

Less subtle but just as effective are sound effects actually coming from: a boom box that’s carried across the stage, a jukebox, and a crying baby (a prop), all sourced via wireless speaker systems. “We just needed that impulse of sound coming from the right place onstage,” Harada explains. Shure PSM-900 in-ear monitor systems carry these effects to a variety of small speakers in the props and set items. This sourcing is also reinforced via the SARA system.

The nearly 200 house speakers include a mix of 135 Meyer Sound units for mains (UPQ-1Ps and UPJ-1Ps), fills, delays, subwoofers and foldback, with 28 d&b E5s for surround. Harada incorporated Meyer’s newer LINA line array for the balcony. “They’re so linear, perfectly sized and powerful,” he explains.

Only the actual onstage musicians have in-ear monitors, worn sparingly, to keep in time with a sound effect or the orchestra under the stage. Onstage foldback is through Meyer Sound UPM-2P and MM-4 units, concealed overhead and on the deck.

“The Band’s Visit is deftly mixed by Liz Coleman on a Studer Vista 5, one of my favorite control surfaces,” says Harada. “The Studer sounds great, my team and I know it well, and it fits into small Broadway FOH positions.”

Related: “On the Town” Sails with Help from StageTec, Mix, May 18, 2015

It’s configured with 210 inputs and 52 outputs, not including orchestra monitoring. “Such granular control is crucial in theater, and the Studer handles it with aplomb,” Harada adds.

Helping Harada manage the details are associate designer Josh Millican and production sound engineers Charlie Grieco and Phil Lojo. Backstage sound duties are handled by Reece Nunez and Greg Matteis.

“I can’t thank my team enough; this is a complex show with a lot of tiny but very important details, and they all helped make it work.”