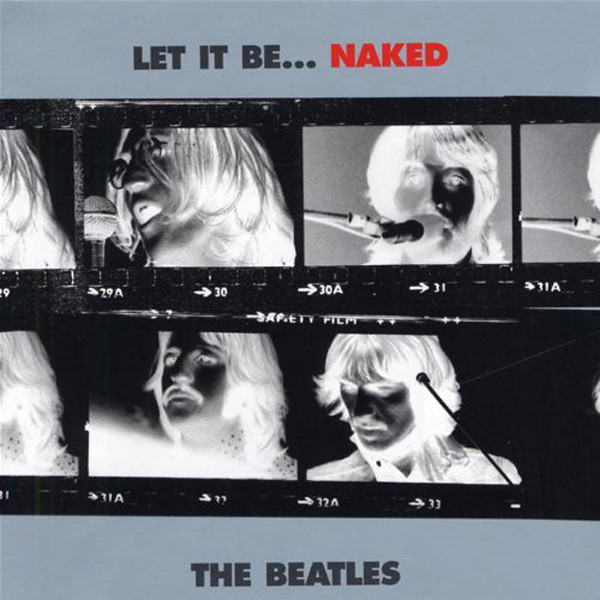

Ever wondered what The Beatles’ Let It Be album would have sounded like had it been properly completed instead of released as a companion disc to their 1970 fly-on-the-wall motion picture of the same name? Such was the charge given to EMI’s Abbey Road Studios by the group’s Apple Corps Ltd. The result is the recently released Let It Be…Naked (Apple/Capitol-EMI).

After the tumultuous sessions for the 1968 album The Beatles (aka, The White Album), the Fabs regrouped at Twickenham Film Studios in London in January 1969 to make a TV special showing the group rehearsing and recording an album. The concept was a “warts and all” view of the band with no overdubs; everything was as live as possible. After those sessions broke down, the production moved to the basement studio of The Beatles’ own Apple offices, where recording continued through the month. The sessions culminated in a historic live performance (The Beatles’ last) on the office’s rooftop on January 30 of the same year with their new temporary “fifth Beatle,” keyboardist Billy Preston (himself an Apple recording artist by the end of the sessions), who played on the studio recordings, as well.

Glyn Johns, who had recorded the sessions, was given the task of mixing and compiling the recordings into an LP (originally titled Get Back) in May of that year, though the group chose not to release it. Johns tried a second compilation in January 1970, though that version also failed to see the light of day. John Lennon, on new manager Allen Klein’s advice, brought in legendary producer Phil Spector to revamp the album in March 1970, which he did, adding orchestration to three tracks and editing others. The result — with studio chatter and quips intact — was the May 1970 Apple release Let It Be, The Beatles’ last original album (although , which came out in 1969, was actually recorded after Let It Be).

In February 2002, following a chance meeting of Paul McCartney and the film’s original director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Abbey Road veteran Allan Rouse received a call from Apple’s Neil Aspinall asking him to take a stab at remixing the album. Rouse had acted as project coordinator for a number of Beatles remix projects, among them The Beatles Anthology, Yellow Submarine Songtrack and Lennon’s Imagine. While the task for those projects had always been to re-create the original mixes known to millions of fans using current technology, the charge for the Let It Be project was different.

“This was not an attempt to remaster an existing album,” Rouse says. “We were asked to make it sound the way the band had believed the finished album was going to sound.” This meant, for the most part, producing mixes that reflected only what the four bandmembers (or five, including Preston) could play live: no overdubbed guitars or vocals, and certainly no orchestras.

In addition, all of the between-song chatter, breakdowns, jokes and ditties — including “Maggie Mae” and the “Dig It” jam — were dropped. Says Rouse, “They just didn’t really fit in with an album of 11 songs and neither did the dialog. Those little bits were fine for a soundtrack album, which Glyn’s was, but they didn’t fit comfortably with the concept of a straight album.”

Rouse tapped two young staff engineers, Paul Hicks and Guy Massey, for the job. Both had worked on prior Beatles projects (and had, coincidentally, started at the studio on the same day in 1994), including the 5.1 surround mixes for the recently released The Beatles Anthology DVD set.

The group took a team approach, making decisions democratically, each chipping in suggestions but deciding with one voice. During a two-week period, the three listened to all 30 reels of 1-inch 8-track session tapes, which had been recorded through a pair of borrowed 4-track consoles onto a 3M 8-track machine. As a reference, the producer/engineers also studied the released Spector album and both of Johns’ versions. “We mainly listened to identify the takes they used,” says Rouse. They also noted where Spector had made any edits, deciding if there was a good reason to either keep or discard those edits. “As it turns out, Glyn and Phil had done most of the legwork. We ended up using the vast majority of their takes.”

But because the group’s mission was to make the best possible album, they didn’t limit themselves to what had been done previously. “Once we started, we would A/B against the Spector disc to see if what we were doing was an improvement,” says Massey.

Upon listening to the tapes in Rouse’s room at the studio, they were transferred into Pro Tools 5.2 using a Prism Sound Dream ADA 8 A/D converter. And, as part of the improvement process, once the recordings were in the digital world, the engineers began researching which takes were the best performances, and, if more than one take of a song had strong attributes, trial edits were made to see what combination would make the best overall performance. “Once we had the building blocks in the digital domain,” says Massey, “we’d delve into a bit more detail. If there were fluffed lines or pops, etc., if there was another take without the errors, we’d try inserting that part from the other take.”

Adds Hicks, “Sometimes we did the tiniest little things. If something wasn’t quite right — if there was a bend in a note or something — we did actually replace it with a slightly better one. Again, our main theme was to make it as strong as possible.”

The live rooftop recordings offered their own special challenges, given that the band was playing on a blustery winter day. Because the group was being filmed, the film crew had chosen an unobtrusive vocal microphone during the sessions, the Neumann KM84i, which features a small capsule on the end of an extension tube, with the mic’s preamp located at the bottom near the floor. (The mic was commonly used for TV talk shows and awards programs.) The same mics were brought upstairs to the roof, where second engineer Alan Parsons simply tied clippings of pantyhose over the capsules to act as windscreens. “The wind noise was actually quite manageable,” says Hicks. “It was really only when they weren’t singing that you could hear it.” For the inevitable hard consonants and mic pops, “We mainly handled that with a combination of filtering and EQ,” notes Hicks. A small amount of de-noising was done using an analog Behringer dynamic filter.

The following is a breakdown of what was done to each Let It Be…Naked track (in running order, along with the mix engineer’s name in parentheses):

“Get Back” (Hicks): While Johns and Martin used a master recorded on January 28, 1969, for the aborted LP and released single, Spector had used a recording from the day before, and the same master is used on this album. Notably absent is the song’s coda, which appeared on the single. “It turns out that the coda had been recorded as an edit piece four or five reels later,” explains Hicks. “Since it wasn’t on the original session recording for the song, it wouldn’t have represented what actually took place in the studio during that take, so it was decided to leave it off.”

“Dig a Pony” (Massey): Those who’ve heard bootlegs of Johns’ mixes know the song originally featured an “All I Want Is You” intro and outro, which Spector removed for his LP. “The tuning is particularly bad in the beginning,” says Massey, prompting the decision to eliminate them in the new version, as well.

“For You Blue” (Hicks): Using the same master as Spector used, Hicks mainly focused on keeping the sounds bright and clear. What was interesting, he says, was learning about the unique sound McCartney got out of his piano. “It’s a fuzzy, metallic sound, which he did by putting a piece of paper in the piano strings, causing them to vibrate against the paper when struck. You can hear on the session tape Paul’s fiddling around, trying to get the right sound.” And because McCartney is playing piano, he does not play bass on the song. “The bass comes from the piano,” says Hicks, with McCartney playing a bass line on the keys. George Harrison’s vocal, it turns out, was one of the few overdubs used. “We took out his live vocal, which was basically a guide vocal. It wasn’t a complete take, really, and I don’t think it was ever intended to be used.”

“The Long and Winding Road” (Hicks): Perhaps the greatest achievement on the album is the improvement to this track, easily accomplished by removing Spector’s overblown orchestra. Actually, though, the master on Let It Be…Naked is not even the one used by Spector; it’s the only take on the album that was changed in its entirety. The group returned to the Apple basement the day after their rooftop show to record three more songs, this one among them. Says Rouse, “Spector had used one take recorded five days earlier.” “This version, recorded on January 31, we felt was a stronger basic performance,” says Hicks. “There’s also a slight lyric change,” adds Rouse, who suggests that, this being the later recording, it represents McCartney’s final lyric choice.

As a listening experience, it’s a first for Beatles fans to hear them play the song instead of an orchestra. The recording features McCartney on piano, Harrison playing lead guitar through a Leslie speaker, Lennon on a newly acquired Fender Bass VI and Ringo Starr keeping light time with his hi-hat.

“Two of Us” (Massey): The same master used by Spector, also from January 31, 1969, features Lennon and McCartney on acoustic guitars, Harrison on electric and Starr providing a simple bass drum/snare/tom beat. By the way, Starr’s drums were typically recorded onto a single track, precluding mixing them into stereo. Small amounts of de-essing and rumble filtering were also performed.

“I’ve Got a Feeling” (Massey/Hicks): A rooftop recording, this song was edited by Massey before being mixed by his colleague. Massey used the best of each of two rooftop takes of the song, creating a version, Hicks says, with the most energy. And while Johns had opted for a studio recording of the song for his version of the album, there was no beating the live performances. Notes Hicks, “I don’t know if it was just the fact that they were playing live and knew it or just because they were so cold, but there was just so much more energy in the live recordings.” Sonically, he notes, the live recordings — minus the wind and pops — are not much different from their studio counterparts, making a surprisingly good match when listening to the album.

“One After 909” (Hicks): Another rooftop performance, though, interestingly, the team did consider using a studio version. “We did research to see if there was another version,” says Hicks. “But it was just much slower, and it had a completely different feel. There was no contest, really. It’s one of the more up-tempo numbers, so we went with the live one.” Hicks is proudest of his drum sound, bringing Starr out to the fore. “We found so many details we wanted to bring out, which we tried our best to do. Everything is a lot more focused.”

“Don’t Let Me Down” (Hicks/Massey): Though not included on Spector’s album, this song was a product of those sessions. A studio version from January 28, 1969, was released as the B-side to the “Get Back” single. This version, however, is an edit of the two rooftop versions. The Beatles recorded a second take because Lennon forgot the lyrics during the first take.

“I Me Mine” (Massey): This song was not originally recorded at Apple in January 1969, though Harrison is seen in the film playing it briefly at Twickenham. In January 1970, Harrison, McCartney and Starr recorded a studio version of the song, with Harrison playing acoustic guitar and singing a guide vocal, McCartney on bass and Starr on drums for the master take. Electric piano, electric guitar, lead vocal, backing vocals, organ and a second acoustic guitar were added as overdubs. The recording was a brief 1:34 in length, so before adding his orchestra, Spector lengthened it by repeating one of the verses, resulting in a 2:25 final master. The Naked team decided to leave in the overdubs — which made the recording complete as The Beatles had envisioned it — and Spector’s edit. “We were originally going to do it unedited,” says Massey, “but if you listen to it at that length, it’s just far too short.” Jokes Rouse, “That was our one concession to Mr. Spector.” Massey also built up the mix as the song progressed by adding elements of the mix as the song enters the second verse.

“Across the Universe” (Massey): Again, while no studio recordings of this song were made at Apple, Lennon is seen playing the song at Twickenham in the film. “Across the Universe” was actually recorded a year earlier, in February 1968, at the same Abbey Road sessions that produced “Lady Madonna” and “Hey Bulldog.” The basic track featured Lennon on acoustic guitar, his vocal and a tom-tom (all recorded onto one track), with Harrison playing a tamboura. At the time, George Martin had added background vocals and animal sound effects. Spector’s version removed the latter two parts, as well as the tamboura, replacing them with an orchestra and a choir.

The new mix features Lennon’s guitar and vocal, Starr’s drums and the tamboura. “Again, because the concept was whatever the guys could play live onstage, we took everything else away,” says Rouse. The ending has been given a spiritual touch, with a building echo (via real Abbey Road tape delay) added.

“Let It Be” (Massey): another recording from January 31, 1969, the day after rooftop, with McCartney on piano, Lennon on Fender Bass VI, Harrison on lead guitar (through a Leslie), Starr on drums and Preston on organ. Three months later in April, Martin added a new electric guitar lead from Harrison, and in January 1970, added backing vocals from McCartney and Harrison, brass and cellos and yet another pass at a Harrison lead. Martin produced the single release of the song, issued in March 1970 (pre-Spector), featuring the April 1969 guitar solo. Upon Spector’s arrival, the song was lengthened by repeating a chorus and issued featuring the January 1970 guitar lead.

The new version features the same master and uses a few edits from other takes, most notably the Harrison guitar solo that came from the take of the song that appears in the film. “We’d always thought that the guitar lead in the version in the film was just really soaring,” says Massey. “We edited it in, just as a trial take, and we all thought it sounded great.”

The album comes with a 22-minute companion “fly-on-the-wall” dialog/music disc put together by the BBC’s Kevin Howlett and engineer Brian Thompson. Howlett listened to more than 80 hours of tapes, recorded in mono by the film crew during both the Twickenham and Apple sessions, discovering a number of previously unknown Lennon/McCartney tunes (which are included on the disc), as well as some other surprises. “I had expected to hear the kind of disagreements and arguing we’ve all heard about,” Howlett tells Mix. “Instead, I heard the bandmembers actually having a good time. By the end, they were, in fact, quite excited about what they were doing.”

Remixing an album by the greatest rock band of all time can be, well, daunting. “It’s hard to make it as up-to-date as stuff nowadays, because it wasn’t recorded these days,” says Massey. “From that point of view, it was a challenge to make it sound as punchy and as present as possible. But it’s a good representation of what they were like then.”

Adds Hicks, “We all collectively felt that we wanted it to stand along all the other Beatles albums, and hopefully, we’ve achieved that.”