Onstage at the Hollywood Palladium last winter, Dave Grohl and his Sound City Players performed with a handful of the artists who appear on the soundtrack to Grohl’s Sound City documentary. Rick Springfield had barely started his last number when the crowd began to roar and Grohl interrupted the proceedings to make a point: “Three f—king chords, and you already know! Congratulations, Rick Springfield for writing a song that they only need to hear one f—king second of to know what it is! How do the other four minutes go?” Cue the sing-along: “Jessie is a friend…”

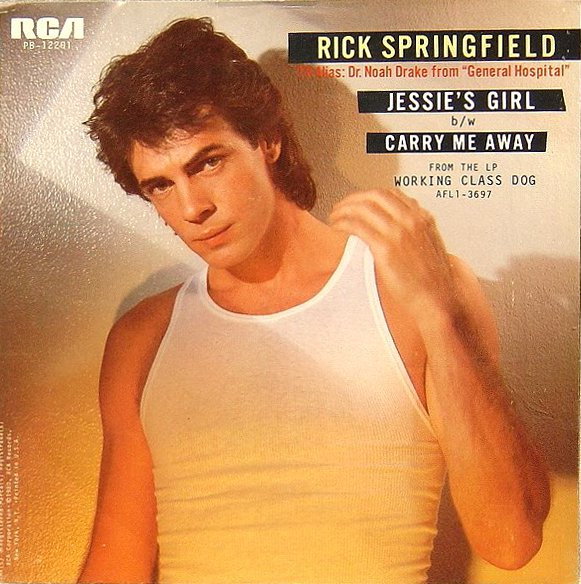

Rick Springfield — an Australian-born musician/songwriter/actor whose given name is Richard Springthorpe—has been singing “Jessie’s Girl” to adoring fans since he recorded the hit at Sound City Studios in 1981. His signature song exploded at the height of his music and acting career, making it seem like the performer was an overnight success—a by-product of effective marketing and the fact that the then-new MTV format rewarded beauty at least as much as talent.

Rick Springfield — an Australian-born musician/songwriter/actor whose given name is Richard Springthorpe—has been singing “Jessie’s Girl” to adoring fans since he recorded the hit at Sound City Studios in 1981. His signature song exploded at the height of his music and acting career, making it seem like the performer was an overnight success—a by-product of effective marketing and the fact that the then-new MTV format rewarded beauty at least as much as talent.

But Springfield had been playing in struggling bands in Australia since the ’60s. Between 1969 and 1971, he put out a few singles on Australian labels with a band called Zoot and as a solo artist. His debut album, Beginnings, was released in Australia just before he moved to the U.S. in 1972. A single off of Beginnings, “Speak to the Sky,” was picked up by Capitol Records and became a Number 14 hit for Springfield, who sang lead and played guitar, keyboards and banjo on the bouncy, folky arrangement. Beginnings then cracked the U.S. Top 40 as well.

Springfield is a strong writer and a multi-instrumentalist—not just a pretty face. But he definitely had that really pretty face. Beginning with his second album, Comic Book Heroes (Columbia, 1973), he was promoted as a teen heartthrob, which proved to be a blessing and a curse to him. On the downside, few critics took his recordings very seriously, and many in the industry believed it when rumors circulated that his label paid fans to buy up his records to jack up his sales numbers.

On the upside? Springfield became massively popular, playing to hordes of screaming girls and garnering him an acting role as the 1980s version of “Dr. McDreamy:” Dr. Noah Drake on the ABC daytime soap opera General Hospital.

By the time Rick Springfield joined the cast of GH, he had signed with manager/promoter Joe Gottfried, a partner in Sound City Studios. Springfield began his third album, Working Class Dog, in Sound City with staff engineer/producer Bill Drescher. Sessions were productive and going well, but Gottfried also asked Keith Olsen—a frequent presence at Sound City whose credits include massive hits with Fleetwood Mac, Pat Benatar, Santana, Foreigner and others—to produce a couple of tracks for the album.

“Rick and I got together and I picked a couple of songs,” Olsen recalls. “I said I would pick one of his and I’d like to bring one in. I probably didn’t need to do it, but there was this song that I had in my back pocket that I wanted to cut with somebody really soon, and that was Sammy Hagar’s ‘I’ve Done Everything for You (You’ve Done Nothing for Me).’ And then I said I really want to do ‘Jessie’s Girl.’ The story just nailed me. Because being a guy, we’ve all been through this: Every guy everywhere has a friend, and he meets his friend’s girlfriend, and we fall, for a moment, in love with that girlfriend. If you ever run into a guy who says, ‘Nope, that never happened to me,’ he’s lying.”

In a 2008 interview on the Oprah show, Springfield said that “Jessie’s Girl” was written about a girl he barely knew. He said he was taking a stained glass-making class with a friend (named Gary, not Jessie) and the friend’s girlfriend, and found himself attracted to the girlfriend. They didn’t interact much, but the experience suggested the scenario in the song. Springfield said that he doesn’t even remember the girlfriend’s name. He changed “Gary” to “Jessie” after seeing that name on the back of another girl’s softball jersey; the name just sounded right to him.

Olsen and Springfield fit the sessions for “Jessie’s Girl” and “I’ve Done Everything for You” into gaps in Springfield’s GH shooting schedule. Manning the famed Neve 8028 console at Sound City was engineer Chris Minto (Kiss, Santana, Pat Benatar, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Quiet Riot, and more), an independent engineer who came up in San Francisco, working for Wally Heider and then at The Automatt, where he originally met Olsen.

“Keith asked me to join him in L.A. to work on his projects,” Minto says. “As a fan of his work, I jumped at the opportunity and moved to L.A. in 1980. When Keith got the call to work with Rick Springfield [in 1981], we had been doing Pat Benatar’s Crimes of Passion together, and Keith pulled Neil Giraldo [Benatar’s guitarist and husband] in to play guitars and bass on Springfield’s session.”

In the Sound City documentary, Springfield feigns having been miffed that Olsen hired a lead guitarist, but Minto says, “I never got the impression that Rick was egotistical at all. He was always very easy to work with. He just wanted whatever would benefit the record.”

Also on the session was drummer Mike Baird. “Because of Rick’s shooting schedule, we had to work quickly; that’s why I brought in Mike,” Olsen says. “His time was like a metronome. If you never want the time to drift, and you don’t want to play to a click like everyone does now, you hire a good drummer. I hired a great drummer.”

Classic Tracks: REO Speedwagon’s “Roll With the Changes”

Minto says rhythm tracks were laid down first: “Every piece was done in the ‘A’ room,” he says. “Drums were typically on a riser, three-quarters of the way toward the back wall, away from the glass, with the drummer looking into the control room. And there were large gobos behind the drums to control leakage. Those gobos at Sound City were really huge, because the ceiling was very high—18 or 20 feet.

Guitars and vocals were then recorded and layered on: “For Neil’s guitars, we typically used AKG 451s with the 10dB pad and an SM57,” Minto recalls. “Neil had custom 100-watt Marshalls and Countrymans, and we recorded his guitars in stereo. He had a rack of digital effects; one amp would be just a clean sound from his guitar, and the other had the effects. We typically used his sound the way he recorded it because it was extraordinary. We recorded his guitars to two tracks, and punch-ins were never a problem because his timing was exquisite.”

After Baird’s count-off, Giraldo sets the tempo of the first bars from that first, unmistakable riff that blew Grohl away—those few moments just before Springfield sings, “Jessie is a friend…”

“Rick’s vocal was to an AKG 414 that I still own,” Olsen says. “And of course, that went into a Neve mic pre, in the console. From there, it was split and I used 75 percent of that and 25 percent of my vocal expander made by Dolby Labs. Then it went to one channel of a 33609 [Neve compressor], and then to the Studer tape machine, which would have been either an A80 16-track or an early A800 24-track. But I know we mixed it down to an A80 2-track half-inch machine at 30 ips. That was my go-to [vocal chain], and that’s what I’ve used on every single artist before and since.”

Minto says, “I think that vocal chain—bringing the return from the Dolby back on the second fader and busing the two of those through a compressor to tape—was a trick that Keith learned from George Martin and Ray Dolby. It added a very nice emphasis to the vocal, especially if the vocalist was soft and might have had the danger of getting lost in the track. It created a nice texture.

“One of the main things on the sound overall, though, was that fabulous-sounding console,” Minto continues. “It had all those fabulous Neve mic pre’s in there that people have been cannibalizing consoles for, for years. To have a console full of those things is magic. It had that wonderful, clear, warm Neve sound.”

Both Olsen and Minto joke that the secret ingredient on “Jessie’s Girl” was actually the “Hit Train”: “Sound City had a railroad track 100 yards away,” Olsen says. “When I first cut the Fleetwood Mac album, you hear some rumbling every once in a while. I went on to do Grateful Dead there, and the train went by. And on Foreigner—that sold, what, 8 or 10 million copies?—I was doing the vocals on ‘Hot Blooded’ and the train went by. So, I started saying, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it. It’s on all my records.’ I started calling it the Hit Train.”

It probably wasn’t the Hit Train that drove “Jessie’s Girl” to Number One, and earned Rick Springfield a Grammy for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance, and made the song an enduring favorite for three decades. So what was it? “It was the story,” Olsen says. “Making pop records, or rock records, is always about nailing the story to the point where the listeners claim it. They hear ‘You’re a real tough cookie with a long history of breaking every heart like the one in me,’ and they think, ‘Oh God, that happened to me!’

“The things that make a hit are always: It’s about the song first, the melody and the lyrics,” he continues. “Second, the performance and how that song is put together. Rick had that part down. He has stage presence to end all stage presence. And thirdly, and definitely last on the list, is the sound. Song, performance, sound—in that order.”

Rick Springfield’s Platinum Working Class Dog album has sold more than 3 million copies worldwide, mostly on the strength of “Jessie’s Girl.” After 30-plus years and dozens of other Top 40 hits, it’s still the song that Springfield is always asked to perform, and he doesn’t seem to mind.

Engineer Minto left full-time engineering several years ago to work on the technology side; he serves as vice president of Miller and Kreisel Sound USA.

Meanwhile, Olsen, whose resume reads like a who’s who of classic rock, continues to engineer and produce in his personal studio/production company, Pogoloco Corporation. Just before the interview for this story, he had finished tracking another Australian act, the young band the Monks of Mellonwah.

“They have this song called ‘Escaping Alcatraz’ that’s full of symbolism about how we all have our own Alcatraz, our own prison that we’re trying to get out of,” he concludes. “I love that they’re writing these unique stories. So, you see? There it is again. The story is most important.”