There are two lessons to be learned from this month’s “Classic Track”: First, persistence pays off; and second, sometimes the master is the demo and the demo is the master.

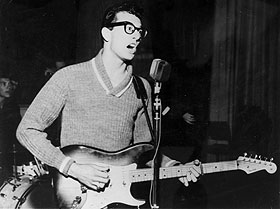

In the winter of 1956/57, Buddy Holly was an artist in transition. After being discovered by talent scout Eddie Crandall in the fall of 1955 and signed to Decca Records in Nashville, by late 1956 Holly found himself without a hit and without a contract. Prior to this, Holly had had three separate recording sessions for Decca between January and November 1956 with legendary country music producer Owen Bradley at his Quonset Hut studio on 16th Avenue in Nashville.

For Holly’s first Decca session, he was told to put down his guitar and concentrate on his vocal, and his band was filled out with Nashville session men. His first single, “Blue Days, Black Nights,” garnered some positive reviews, but it didn’t sell. On his second visit to Nashville in July 1956, Holly insisted on playing guitar and singing. He also insisted on having members of his band back him and on recording original material. It was during this session that a master take of “That’ll Be the Day” was recorded. When the Decca executives heard the fruits of this session, they were unimpressed—so much so that, according to drummer Jerry Allison, one of the execs proclaimed that “That’ll Be the Day” was the worst song he’d ever heard. “The people in Nashville didn’t like it at all, which hurt my feelings, of course,” says Allison more than 50 years later.

When Holly returned for what would be his final Decca session in November 1956, Nashville session musicians once again backed him, and Holly was again told to set down his guitar. After the failure of Holly’s first single and the disastrous “That’ll Be the Day” session, Decca was not taking any more chances. At this session, the Holly single “Modern Don Juan” was recorded—it flopped.

While Holly was going through his trials and tribulations with Decca, another development was under way: Musician/composer Norman Petty had set up a recording studio in Clovis, New Mexico, a small town just west of Holly’s hometown of Lubbock, Texas. Petty financed his studio with royalties he had earned from his trio’s hit recording of the Duke Ellington song “Mood Indigo.” At first, the studio was intended to be for private use, but word quickly spread and it became a hot spot for recording local talent.

While still signed to Decca, Holly decided to record some demos in Clovis with Petty. Holly was in search of his sound and perhaps a more comfortable place to record. His first attempts were a seven-song session of mostly original songs in the spring of 1956, followed by a session of two cover songs that winter. At this point, Petty shied away from further developing Holly’s music—possibly because of Holly’s recording contract with Decca or because Petty didn’t feel that the material that Holly brought to the sessions was strong enough. Either way, by the time Holly showed up for a third demo session on February 24, 1957, both of those circumstances had changed.

Petty had suggested that Holly get some more original songs and a band together. When they were well-rehearsed, he should come back and cut a demo that they could pitch to record companies. After being released from his contract with Decca in December ’56, Holly was determined not to fail; he had developed strong ties to many musicians in Lubbock, and by the time of the “That’ll Be the Day” session with Petty, he had put together a cohesive group. On the session were longtime friend and bass player, Larry Welborn, and guitarist Niki Sullivan, who also sang backing vocals for Holly with husband-and-wife team Gary and Ramona Tollett. Holding it all together on drums was Allison, Holly’s best friend and co-writer of “That’ll Be the Day.”

Some of the gear used to record “That’ll Be the Day,” from top: Norman Petty’s Ampex 350 tape machine, and RCA 44 and RCA 77 ribbon microphones

Photos: Joe Beine

“That’ll Be the Day” had been written in the spring of 1956 in Allison’s bedroom after Holly and Allison had seen the John Wayne film The Searchers. In the film, Wayne’s character repeats the phrase “That’ll be the day” several times. “We started writing the song one day when we were practicing,” Allison recalls. “I had a big bedroom at my folks’ house where I kept my drum set, and Buddy had his guitar, and we were just practicing and fooling around with the guitar. Buddy said we ought to write a song, and I said, ‘That’ll be the day,’ and Buddy said, ‘That’s a good idea,’ and in about 30 minutes we wrote us a song.”

At the time of the session at Petty’s studio in February of 1957, “That’ll Be the Day” seemed quite old to Holly. He had unsuccessfully recorded it for Decca eight months earlier, and while the band had rehearsed the song and had it ready, Holly’s focus was on a newer song called “I’m Looking for Someone to Love,” which he thought would make a better A-side.

Sessions at Petty’s studio usually started in the evening. The studio, at 1313 7th St., was in a building that had once housed a family-run grocery store. Its proximity to 7th Street, the main thoroughfare in and out of Clovis, meant a lot of traffic noise during the day, so recording at night was the only practical way to use the studio. This, coupled with the fact that electricity was more reliable at night, made all-night recording sessions the norm.

The recording space was hand-built by Petty in the early 1950s. It measures a cozy 20×24 feet and features individually tuned polycylindrical walls that run vertically on one wall and horizontally on the opposite, with no two surfaces in the room running parallel. Plush curtains cover the cement outer wall, while fabric and carpet are used to diffuse reflections throughout the room. Tall sound baffles, referred to as “drum walls” by Gary and Ramona Tollett, were used to isolate singers and instruments. Double-paned windows provide views between the tracking room and the small control room, between the tracking room and an additional iso booth/waiting room, and between the control room and iso booth. Down a narrow hall that runs behind the studio floor are three more rooms: a kitchen, bathroom and sleeping/living quarters. Petty’s studio was a fully equipped residential retreat recording studio—a concept that was decades ahead of its time.

Recording “I’m Looking for Someone to Love”/“That’ll Be the Day” began around 9 p.m. on that cold Sunday evening in February. “I’m Looking for Someone to Love” was new, and the band needed several hours of rehearsal and a number of takes to record the song; they got the final take somewhere around 2 a.m. With Monday-morning responsibilities looming back in Lubbock, the group began recording what was to be the demo’s B-side: “That’ll Be the Day.” Luckily, that song was well-rehearsed; the song had become a standard for Holly and his group, and Allison says it was a hit with the kids of Lubbock long before it was a hit record: “We had played it in between [sessions]; we played it at dances. They liked to dance to it, and we got a good feeling and reaction from it.” Because the song was so familiar, the B-side only took two takes to record.

For the recording of “That’ll Be the Day,” all of the musicians and singers were on the main studio floor: drums, acoustic bass, electric guitar, Holly singing the lead and the trio of backing singers. Knowing this while listening to the recording is evidence that a great deal of work and thought went into the building of this acoustic space.

A 5-channel Altec broadcast mixer was the heart of the small control room. The mixer had been modified to allow signals to be sent to an echo chamber in the attic of the service station next door. The echo chamber featured no parallel surfaces and a concave plaster ceiling with tiled floor and walls. It had been built by Petty with Holly’s father and brother, who owned a tile business. The studio’s main tape machine was a mono Ampex 350 purchased in 1955. A secondary portable Ampex 350 was used for playback when sound-on-sound overdubbing was required, and monitoring took place via Altec 604 speakers. On the studio floor, classic ribbon and tube microphones were used to capture the instruments and vocals. RCA 44 and 77 models, Bang and Olufsen Fen-tone, Altec M-11 and Telefunken U47 mics were all used by Petty at this time.

With the demos recorded, the next step was to take them to record companies in hopes of landing a contract. When attempts to interest Roulette and Columbia in the songs failed, Petty brought the recordings to Murray Deutch, who worked for Southern Music, Petty’s publisher. Deutch gave the demo to Brunswick Records’ Bob Thiele, who saw potential in “That’ll Be the Day.” In May 1957, Thiele convinced Brunswick to release the demo as a single by The Crickets. The terms of his previous deal with Decca prohibited Holly from re-recording the song for another label, so Petty and Deutch hatched the plan to release it under a group name in place of Holly’s name alone.

The record took a little while to catch on, but thanks to Thiele’s support, “That’ll Be the Day” became a Number One hit and a million-seller in the fall of 1957, and Holly became a rock ’n’ roll star of the highest order. Today, more than 50 years after Holly’s tragic death in the plane crash that also took the lives of the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens in 1959, you can find the original Decca master of “That’ll Be the Day” on YouTube. On it, Holly sang high above his customary vocal range, and the reverb-y sound seems like an attempt to turn the singer into a Gene Vincent type. It took the faith and perseverance of Holly, Petty, and then Deutch and Thiele to deliver Holly’s authentic, unique sound to the public.

Ron Skinner is a producer/recording engineer for CBC Radio. This article is part of a planned book about the career of composer/producer/studio owner Norman Petty.

The Difference in the Details

After the success of “That’ll Be the Day,” Buddy Holly began releasing material under his own name on Brunswick’s sister label Coral in tandem with releases by The Crickets on Brunswick—although all the recordings were performed by essentially the same group of musicians, with Buddy Holly, Jerry Allison and the new addition of Joe B Mauldin on bass as the core group. This decision was made in order to maximize the potential of the material that Buddy Holly and The Crickets would record with Norman Petty in Clovis over the following 18 months.

In the early days of rock ’n’ roll, singles were king in the marketplace, and Brunswick and Coral would release the material at a break-neck pace when compared to how music is released and promoted today. As the music was recorded, a decision was made either to release the song as a Buddy Holly record or as a one by The Crickets. The general distinction between the two types releases concerned the addition of backing vocals to the Crickets’ recordings. The Buddy Holly material was usually more sparsely arranged. “That’ll Be The Day,” the first single by The Crickets included backing vocals, and because of that, it most likely set the standard for the sound of future releases by The Crickets. “When the record came out, it said Vocal Group with Orchestra and we weren’t a vocal group at all,” explains Jerry Allison. “Joe B and I, we still can’t sing.”

In fact, most of the musicians on “That’ll Be The Day,” as well as the other Crickets and Buddy Holly releases, did not get credit until years later. Larry Welborn, who played bass on “That’ll Be The Day” but was not a member of The Crickets, wasn’t even aware at the time that he had played bass on the released version of the song. “I didn’t know it was me on the bass for quite a while, maybe a couple years later when Joe B told me about it.” In all, there were three vocal groups who sang the backing vocals on the Buddy Holly and The Crickets recordings: the husband and wife team of Gary and Ramona Tollett on “That’ll Be The Day,” a vocal group called The Picks, and later, a vocal group called The Roses, who also sang with Roy Orbison. None of these performers would be given credit for their work until the advent of the CD and the re-issue boom of the 1980s.