The first time producer Jim Rooney heard Iris Dement sing one of her own songs was around 1991. He was in the office of MCA Nashville music exec Renee Bell, and she shared a live recording of DeMent singing “Our Town.” As the singer/songwriter’s sweet, lilting voice filled the room—telling the song’s nostalgic story of small-town life—Rooney thought, I missed that boat.

Some weeks earlier, the producer had been invited to see DeMent perform on a night of Kansas City writers at the Bluebird Café. “So, I went down there but the place was packed,” Rooney recalls. “I was squeezed in almost all the way to the bathroom, and I could barely see the stage in a mirror that they’d put up behind the bar so you could look around the corner. Two or three other people played, and it wasn’t inspiring. I just didn’t hang around.”

Soon after his visit with Bell, Rooney met DeMent at Jack’s Tracks, the studio where Rooney was based at the time. DeMent had come in to sing harmony on an Emmylou Harris track, and Rooney learned that Harris’ steel guitar player, Steve Fishell, was set to produce DeMent’s debut album. Hearing her sing in the studio, Rooney again said to himself, “Boy, I really missed a big boat.”

Soon after his visit with Bell, Rooney met DeMent at Jack’s Tracks, the studio where Rooney was based at the time. DeMent had come in to sing harmony on an Emmylou Harris track, and Rooney learned that Harris’ steel guitar player, Steve Fishell, was set to produce DeMent’s debut album. Hearing her sing in the studio, Rooney again said to himself, “Boy, I really missed a big boat.”

“A month or two passed, and I got a call from Ken Irwin at Rounder Records, and he said, ‘Would you be interested in working with Iris DeMent?’ I said, ‘Well, yes I would! But I heard that Steve Fishell was going to do that.’ Apparently, it hadn’t worked out with Steve Fishell, so I was glad to get another chance. But I’d still only heard that one song.”

To get things rolling, Rooney and DeMent set up a one-on-one meeting. “We got together at my apartment and sat at my dining room table,” he recalls. “I said, ‘So, play me some songs.’ She said, ‘Do I have to?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know how else we’re supposed to do this.’ She was very shy, and she really hadn’t performed a whole lot. She’d done coffee houses in Kansas City where she was from. She’d had very little experience playing with other musicians.”

One of the songs that DeMent played for Rooney, and one of his favorites from the start, was “Let the Mystery Be,” DeMent’s gentle, tongue-in-cheek observation on the origins of life, and afterlife.

Some say once you’re gone you’re gone forever and some say you’re gonna come back

Some say you rest in the arms of the Savior if in sinful ways you lack

Some say that they’re comin’ back in a garden

Bunch of carrots and little sweet peas

I think I’ll just let the mystery be

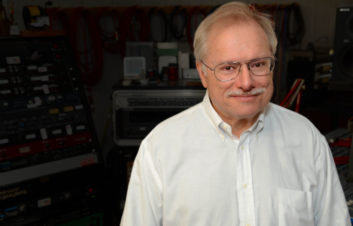

Dement and Rooney both came away from their meeting with a list of songs for her to record, and Rooney took a little time to consider the best way to capture all the freshness of DeMent’s ideas without belaboring them. He realized that a smooth-running session would hinge on seasoned support, so he enlisted a band of A-list musicians, and engineer Rich Adler, whose credits included Johnny Cash, John Hartford, Dolly Parton, and more.

“Jim put together a band that was very sensitive to what she was trying to do, in terms of the tempo and the dynamics of the performances, and it made the process as natural as possible,” Adler says.

DeMent’s core band on the album sessions included Stuart Duncan (fiddle, mandolin), Pete Wasner (piano), Mark Howard (acoustic guitar), Al Perkins (dobro), and Roy Husky, Jr. (upright bass). Both Rooney and Adler recall Husky’s talents with great admiration. Husky, who died of lung cancer i 1997, was revered not only for the musical foundation he gave every session, but also for his leadership and rock-solid chart-writing skills.

“Roy made charts for every song he would play on in the studio,” Adler says. “Even in the rare cases when somebody would come in with charts already made, Roy made his own chart anyway. He made these charts on three-by-five index cards that he carried around in his shirt pocket.

“Sometimes when the other guys were making their own charts, if they got to a spot in a song where they either couldn’t make their charts fast enough, or there was a little bit of ambiguity about what the chord changes were after a run-through, people would go over to Roy and check his chart because he always had it right. It was no wonder everybody wanted him on their sessions.”

“Before we went in to record the album, Iris and I got together with Mark and Roy at Jack’s Tracks, just to get her comfortable working with them,” Rooney explains. “Then, the day before we were going to record, Iris and I were comparing our song lists, and hers had changed. I said, ‘Well, wait a minute, Iris. What happened to ‘Let the Mystery Be?’ She said, ‘Oh, I don’t know. I don’t know.’

“I said ‘Well, I know! That’s why I’m working with you. I think that this life is a mystery. And anybody who thinks they’ve got it figured out is either a liar or a fool. I want that song.’”

DeMent conceded, and the following day, Rooney, Adler and the musicians settled into Cowboy Jack Clement’s Cowboy Arms Hotel and Recording Spa. “I had recorded Nanci Griffith there, and John Prine,” says Rooney. “That’s a nice big room—a wonderful room for acoustic music—where everyone could sit in a circle, and you get a wonderful blend.”

“Jack had one of the earliest versions of what we would now call a pretty established, sophisticated home studio,” Adler says. “He bought a large home, a couple of miles from Music Row, and he converted the entire attic of the house into a studio. It was unusual in the respect that there was no window—no visual connection—between the control room and the main studio space. Whatever communication took place between the studio floor and the control room was all over the microphones and the talkback system.”

The Cowboy Arms was equipped with a Sound Workshop console and a recently acquired Studer 24-track tape machine. Adler recalls that the studio had a limited inventory of outboard gear, but he carried a rack of his own, including several Pultec EQP-1As and an EQP-5, and an ADR Compex compressor/limiter that he especially liked.

Adler also brought along the Neumann U87 mic they used for DeMent’s voice. He says he learned from earlier years in his career, working on staff at Universal Recording in Chicago, how to take care of his microphones, and how no two U87s necessarily sound the same.

“I had a U87 that I’d had rebuilt here in Nashville by Fred Cameron, and it was in really good condition, with the capsule replaced,” Adler says. “On the originals, the diaphragms were made out of material that was seven microns thick. The capsule in my U87, the material was three microns, and it sounded unique. I really liked that on vocals.”

On acoustic guitars, Adler says, “At that time, I frequently used guitar mics with a tight cardioid pattern, such as the AKG 451, but on this session I think I used Neumann KM84s. I had several of those that were really good guitar mics. I would place them four or five inches up the neck from the sound hole to avoid getting a boomy sound, especially in a live situation.”

On Husky’s upright bass, Adler used a mic-DI combination. “I still have that mic—a Sony C38B, one of their first solid-state mics,” he says. “The direct feed was either from the pickup that he had in his bass or sometimes I had a clip-on pickup that I would use, in case there was a note that wasn’t speaking distinctly. That was just to slightly augment the microphone track. The mic was the main sound, and I used a Pultec equalizer as well as some kind of compression that I can’t remember—those pieces were part of getting a really good bass tone.”

“The sessions were all live and they happened very quickly,” Rooney says. “Mark [Howard] and Al [Perkins] split the solo. Mark does the first part and Al does the second part. The only overdubbing we did later was for harmony singing. Iris has this quality of emotion in her voice where you know you’re capturing something special, and I must give Rich great compliments here for doing that. You have to be ready to go when an artist like Iris is recording and not be messing around with technical details like microphones or earphones that don’t work.”

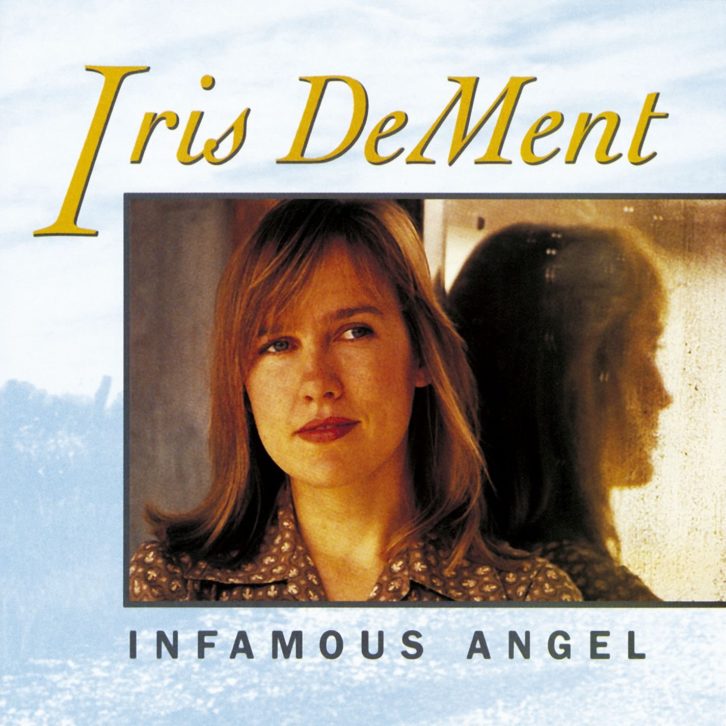

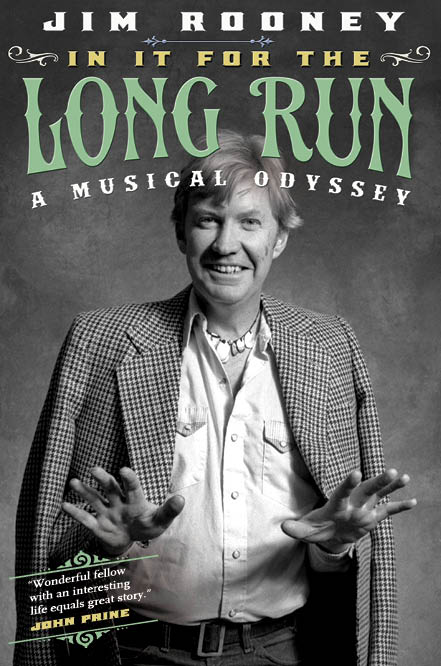

DeMent’s first album, Infamous Angel, was released in January 1992 to critical acclaim. The liner notes featured a short appreciation by the late John Prine, with whom DeMent later recorded several duets.

“One night after receiving a copy of ‘Let the Mystery Be,’ I was listening to the tape while frying a dozen or so pork chops in a skillet,” wrote the ever humorous and brilliant Prine. “Well Iris DeMent starts singing about ‘Mama’s Opry,’ [Track 10 on the album], and being the sentimental fellow I am, I got a lump in my throat and a tear fell from my eyes into the hot oil. Well, the oil popped out and burnt my arm as if the pork chops were trying to say, ‘Shut up, or I’ll really give you something to cry about.’ Of course, pork chops can’t talk. But Iris DeMent’s songs can. They talk about isolated memories of life, love and living. And Iris has a voice I like a whole lot, like one you’ve heard before—but not really.”

The songs on Infamous Angel are still great fan favorites, and the production team of Rooney and Adler carried on working with Dement to make her second record, My Life. Rooney also produced DeMent’s fourth, Lifeline, and continues to work as a folk musician and producer. Adler now operates his own studio, Sound Wave Recording in Nashville.

The song “Let the Mystery Be” recently got a second wind when it was chosen as the theme song to season 2 of HBO series The Leftovers. “That’s not something she pushes for,” Rooney says. “It just happens because her songs are so compelling.”