Texas Gold.” />

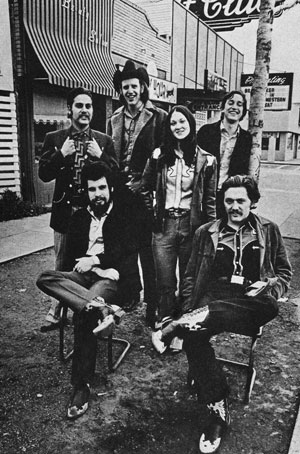

Asleep at the Wheel, 1973: (L to R, rear) Gene Dobkin, Ray Benson, Chris O’Connell, Floyd Domino. (L to R, front) Lucky Oceans, Leroy Preston. All but Dobkin appeared on 1975’s Texas Gold.

Asleep at the Wheel co-founder and leader Ray Benson estimates that around 100 musicians have cycled in and out of his group over the course of more than 40 years. He is the lone original member of the band that started up in West Virginia in late 1969, was talked into moving to Berkeley by George Frayne (aka Commander Cody) in 1970, wowed the Bay Area with its spirited and eclectic mix of Western swing, hardcore country and Big Band flavors, and then was lured down to Austin by Willie Nelson in late ’73, shortly after Willie himself had relocated there. Four decades later, Benson and his ever-shifting band are still going strong, a vital part of Austin’s musical landscape.

But when Asleep at the Wheel started making albums in 1973, there wasn’t much of a recording scene in Austin, so when the band signed its first record deal, they stipulated that they wanted to record in Nashville—just as Willie had been doing until 1973, when he recorded successive albums in New York/Memphis and Muscle Shoals. (His 1975 breakthrough, Red Headed Stranger, was the first record he made in Texas, at Autumn Studios in Garland, near Dallas.)

“Our first album [Comin’ Right At Ya, 1973] was 8-track at Mercury [Studios in Nashville],” Benson says. “We signed with United Artists when we were still living in the Bay Area, and we said we wanted to record in Nashville.” Performing at a DJ’s convention there, the group asked if they could borrow a fiddle player for a number, “because we didn’t have one at that time,” Benson recalls, “and it turned out to be Buddy Spicher, who was one of the top guys. He played with us on [Bob Wills’ Western swing classic] ‘Take Me Back to Tulsa,’ and afterwards he said, ‘Wow, you guys are great!’ We said, ‘Thanks, Buddy, but we need a producer. Any ideas?’ And he said, ‘The best guy would be Tommy Allsup—he played with Bob Wills and was with Buddy Holly, and he’d probably understand what you’re trying to do.’ And he did. He was great. He let us do what we wanted and helped us do it, which was pretty much to play everything live in the studio and then overdub anything we needed. We still like to work that way.”

That eclectic first album showed that Asleep at the Wheel was not going to be easily categorized. Besides their love of Western swing, which was hardly in fashion at the time (despite the popularity of Merle Haggard’s 1970 album, A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (Or, My Salute to Bob Wills), the group also covered old country and honky-tonk tunes by Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, Johnny Horton and Hank Snow, and had a handful of solid originals, most written by AATW’s Leroy Preston who, with Benson and Chris O’Connell, was one of the band’s three lead singers.

The group’s electrifying live sets had even greater scope, encompassing countrified blues, R&B and jazz elements. With their long hair and loose onstage demeanor, they appealed to hippies, but they could definitely sing and play, so they became a magnet for fans and musicians who were looking for engaging country music outside the Nashville mainstream. Having Allsup producing was a feather in their cap, as were the guest appearances of fiddlers Spicher and the great Bob Wills alumnus Johnny Gimble. AATW steel guitarist Lucky Oceans and pianist Floyd Domino could obviously hold their own against Nashville pros, too.

Despite good buzz, the first album was not a commercial success, and for their eponymous second album, released in 1974, their new label, Epic Records, steered them to producer Norro Wilson (best known as a writer of hits for Tammy Wynette, Charlie Rich, Loretta Lynn, et al) and sessions at Studio B at Columbia’s Quonset Hut, engineered by Lou Bradley. “Norro also let us do what we wanted,” Benson says, “so that was a good experience, too.” The album—which included Spicher and Gimble again, and introduced new AATW bassist Tony Garnier—produced the group’s first (minor) hit, “Choo Choo Ch-Boogie,” an old Louis Jordan number.

By the time the group was ready to make their third album, they were well-ensconced in Austin and decided to make demo recordings of three of their new tunes at a studio in town. “The place we found was called PSG—run by a guy named Pedro Gutierrez,” Benson says. “It was an 8-track room he had built himself, with mostly Sony gear, and he had also built the board, which had no marks on it—there were no numbers, no nothin’, and the recording room was a concrete floor and cinder block walls. So we recorded three songs there—‘The Letter That Johnny Walker Read,’ ‘Bump Bounce Boogie’ and one other tune, and we sent it to Epic, who said: ‘These songs are terrible. This is awful!’” Benson laughs. “And, of course, ‘Johnny Walker Read’ became our only Top Ten record ever.” But not for Epic. “We signed with Capitol, and they let us go back to working with Tommy Allsup for the Texas Gold album.”

“The Letter That Johnny Walker Read” started with the title. Benson says, “Chris Frayne, Commander Cody’s brother—who did all the artwork on Commander Cody’s albums and also painted the rope lettering on our bus—came to me and Leroy Preston and said, ‘I’ve got a great title for a country-western song: The Letter That Johnny Walker Read.’ It was a great title, and so we wrote a song around it and did the demo of it, and we actually sent it to Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton, thinking it would be perfect for them. Of course, we didn’t know them and just sent it to some address we got, so they probably never heard it. But it’s got that recitation that I wrote with Porter Wagoner in mind.”

It’s a honky-tonk number, with some Western swing flavors (the unison fiddle, steel and horn parts), that has lead singer Benson as a sodden character named Johnny Walker, in a barroom “drinking his namesake… too drunk to care.” Chris O’ Connell sings the wife’s pleading letter, which begs Johnny to come home to her and the kids, or she’ll leave. It’s a sly, borderline-parodic weeper, “but Chris is what made it work—what an incredible singer she was,” Benson says.

With the exception of two Bob Wills-associated songs—“Fat Boy Rag” and “Roll ’em Floyd”—which were recorded live-to-2-track, with no reverb or EQ, by British engineer Roger Harris at KAFM Studios in Dallas (12 musicians at once!), the rest of Texas Gold was cut at Jack Clement’s Studio in Nashville by engineer Billy D. Sherrill. In 1975, there was still somewhat of a divide between the old-school establishment Nashville types and folks who were more sympathetic to longhairs and the weed that invariably came with them.

That would certainly describe AATW. The album they made in Clement’s Studio B “got its name because we had brought some Acapulco Gold [pot] with us—it was gold-colored; just beautiful,” Benson says fondly. “So we’d say, ‘Here, have some Texas Gold!’ Of course, we didn’t tell anybody at the record company.” And Clement’s turned out to be a most hospitable environment. “It had a little ‘groove room’ upstairs that had a waterbed-like thing and was a great place to smoke pot and have fun,” Benson laughs.

“That was the ‘Fur Room,’” clarifies Billy Sherrill, still an active engineer in Nashville. “The floor and the bed and an S-shaped couch that was part of the bed were all covered with fur up to about waist-high, and from there up it was mirrors. Then, on the ceiling it had parachute material, and Cowboy [Jack Clement] put twinkling Christmas lights behind it. There were a lot of nasty things that went on up there,” he laughs.

The studios, which years later became Sound Emporium, were downstairs in the converted house. The space in Studio B’s L-shaped tracking room was nearly maxed-out by AATW, which had grown to nine members by the time they made Texas Gold, even adding some outside musicians, such as Gimble and some horn players. The room had an alcove for drums—actually a small hallway where Clement constructed a gazebo that could be baffled off with Plexiglas to keep leakage down. “It didn’t help a lot,” Sherrill says, “but the leakage in that room kind of worked for you and added to what was already a cool-sounding room.”

The control room was equipped with a Quad 8 console (“which had fabulous-sounding mic pre’s and 3-band EQs,” Sherrill says), an Ampex MM1000 16-track and JBL 4320 monitors. “We had LA-2A compressors, but they also had a bank of LA-3As and 1176 transistor fare. In Nashville at that time, people were moving away from tubes to solid-state.”

Sherrill notes that, “the [Neumann] 87 was the standard vocal mic at that time in Nashville. I usually used [Shure] 57s on guitar amps; sometimes a [Sennheiser] 421, depending on the guitar player. The piano would have gotten two [AKG] 414s, which I still use on piano.” Horns were often captured with RCA 77s, occasionally with an RE-20 or an RCA 44. “Drums ended up being on three tracks. I’d usually have a 421 on the toms, a 57 on the snare and an RE20 on the kick. We’d use 87s overhead and a [Neumann] KM 84 on the hi-hat. Since we were so limited in tracks, you sort of had to mix as you go.” Sherrill mixed the album on the same console, using some EMT plate and chamber for enhancement.

Sherrill says that producer Allsup was “a great guy, fun to work with, and also a fabulous player”—he plays six-string “tic-tac” bass on “Johnny Walker.” Of that song, he says, “That was one where we all went, ‘That’s got to be a hit!’ The story is so cool, and that was a big story-song era. The band was great, of course. They were rehearsed and ready-to-go, which always makes life easier for everyone.”

“The Letter That Johnny Walker Read” shot to Number 10 on the Billboard country singles chart in the summer of 1975, and Texas Gold hit Number 7 on the country album chart. A second single, “Bump Bounce Boogie,” sung by O’Connell, made it to Number 31. The band’s paydays immediately got bigger, and they found themselves on prestigious tours for a period “where we’d have 25 to 35 minutes in the opening slot,” Benson says. “We had three vocalists, and we’re playing Count Basie, Bob Wills and Louie Jordan, and all people really wanted to hear was ‘Johnny Walker’ and ‘Rocky Top,’ so it was a little frustrating.”

Asleep at the Wheel never abandoned their eclecticism and never tried to repeat the formula of their lone hit single. “It was always a battle,” Benson says. “The record companies were always saying, ‘How are we gonna make these guys commercial?’ So we would walk that fine line between trying not to record anything too stupid and still keep the vision of what we wanted to do.”

Time has proven that philosophy to have been the right one.