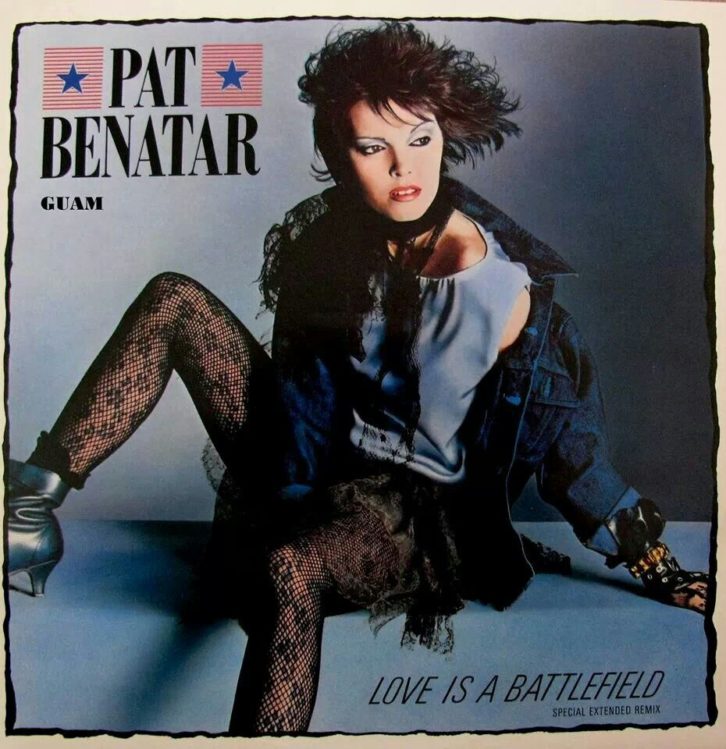

It’s fortunate that most creative people are extremely confident in their visions and fight for their beliefs. Many hits would not see the light of day if not for the insistence of the musicians, as too many times, a record company has vetoed a track that went on to become a monster song. And so it was with Pat Benatar’s “Love Is a Battlefield,” one of the two new studio tracks that Benatar and her cohorts recorded for the Live From Earth album in 1983.

The song, about the angst of teen love, was the perfect follow-up for Benatar, who had become one of the strongest female voices of the late ’70s and early ’80s, behind such mega-hits as “Heartbreaker,” “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” “You Better Run,” “Treat Me Right,” “Promises in the Dark” and “Shadows of the Night.” “Love Is a Battlefield,” which features some quirky production elements, became one of her most successful releases, going to Number 5 on the Billboard singles charts and becoming a Number One rock album hit.

The song, about the angst of teen love, was the perfect follow-up for Benatar, who had become one of the strongest female voices of the late ’70s and early ’80s, behind such mega-hits as “Heartbreaker,” “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” “You Better Run,” “Treat Me Right,” “Promises in the Dark” and “Shadows of the Night.” “Love Is a Battlefield,” which features some quirky production elements, became one of her most successful releases, going to Number 5 on the Billboard singles charts and becoming a Number One rock album hit.

Arranger, co-producer (along with Peter Coleman, who also engineered), guitarist, creative visionary and Benatar’s husband since 1982, Neil Giraldo recalls how, like with most songs sent to them (and even those he co-wrote), he always had a penchant for changing them around, sometimes quite radically. Written by Mike Chapman and Holly Knight, “Love Is a Battlefield” came to them via a very slow, acoustically performed demo.

“The demo was Mike singing with an acoustic guitar and it had a nice, minor-y feel to it,” Giraldo says. “Something about the song really intrigued me. I happen to love songs that have a minor feel. I always loved ‘Working Class Hero’ by John Lennon because of its dark nature. ‘Battlefield’ also had a dark thing going on that was really interesting, so I thought, ‘I think I should give this a shot because I think I can do something interesting with it.’ I felt the essence of the song was there; I just needed to figure out how to pull it out.

“The first thought I had was to speed it up,” he continues. “Because whether I write the song or the wife and I write it together, or the song is given to me, I try to completely shift it around 360 degrees just to see what comes out of it. I try to make it totally different from its original thing. That was even the case with ‘Promises in the Dark,’ which I wrote on the piano as a slow ballad. On the record, I ended up speeding that up and giving it a whole different texture, too.”

Giraldo began work on “Battlefield” the first day he owned a Linn drum machine, which, at the time, was quite revolutionary. Because he really didn’t know what he was doing with this new machine yet, his experimentation paved the way for a happy accident.

“Normally when we went into the studio, I would play live with Myron [Grombacher, drummer] and I would add bass afterward and the vocal would be going down with the guitar and drums,” Giraldo says. “This time, the Linn came first. I started programming a beat just for the hell of it, playing a boogaloo sort of thing, and I was just hitting the buttons, checking out the machine. I had no idea what I was doing, but then I started liking the groove and thought, ‘Maybe I should fix this up,’ and I hit the Edit button by accident and made the 8-bar phrase a 6-bar phrase. I was so mad because I thought I had a great groove. I didn’t necessarily think it was a great groove for ‘Battlefield,’ but it was a great groove. Then it hit me when I made the ‘mistake’ that it would be a great groove for ‘Battlefield.’ Then I was playing that 6-bar beat, letting it flip around all over the place, and I started adding the keyboards and guitars and building the song from there. I remember playing it for people who said, ‘You can’t use a 6-bar phrase. It’s not the same in every verse and chorus,’ and I said, ‘I don’t care.’”

Even Grombacher wasn’t sure about it. “I remember having him play a hi-hat and snare on top of the loop,” Giraldo recalls. “The loop had everything in it — hi-hat, kick and snare — but I had him play top kit: hi-hat and snare with fills to give it more of a live feel between the machine and the live player. He said, ‘You can’t do that. It’s six bars, it flips around. The kick drum is in the wrong spot here.’ I said, ‘I don’t care about any of that. I like the way it feels.’ Everybody was trying to count it out as even to where it was supposed to be, and I said, ‘Just imagine it as being a normal 8-bar phrase and play into it.’” Giraldo ended up close-miking the hi-hat and snare.

The song was cut in Studio B at MCA’s Whitney facility in Glendale, Calif., which was equipped with a Neve console. “We didn’t use that much outboard gear,” Giraldo recalls. “We basically went through the Neve, used the Neve EQ and a little bit of compression. We used an 1176 compressor on the voice, a little Pultec, but not a lot. We also used some EMT 250 reverb on the voice and possibly the guitar.” For the guitar, Giraldo used a Fender Strat and a Roland JCM-120 amp with AKG 414 mics on the speakers. “A lot of those vibrato fills was me bending the neck back, not so much a vibrato part,” he notes.

After the vocals were recorded using Neumann U67s, Giraldo decided to have a little fun. He asked Benatar to open the song with some talking. “I was doing it as a joke, like a lot of those speaking bits The Supremes had on their records from the ’60s. So for fun, I thought we should do it. I told Pat, ‘Just talk. Have some fun with it.’”

And the whistling outro? More fun. “I knew she could whistle, so I said, ‘Why don’t you whistle at the end?’ She said, ‘Are you nuts?’ I thought, ‘It worked for Otis Redding on “Dock of the Bay,” so just try it.’ She said, ‘Whatever.’ She always thought I was nuts anyway,” Giraldo says with a laugh.

Engineer Coleman also thought Giraldo was nuts and didn’t much care for this particular track. “He is such a classy guy that it wasn’t until the record came out and it was a hit that he told me, ‘When I was doing the record, I hated absolutely everything about it. I thought it was the totally wrong direction,’” Giraldo recalls. “He told me that he went home while working on the song, and said to his wife, ‘I have to open the Scotch. I don’t know how to tell Neil tomorrow that I think he’s totally going in the wrong direction.’ He drank the Scotch and listened to the rough tape we had made and said, ‘Wait a minute, I’m beginning to understand it. I think he might be onto something.’ But he never said a thing to me until the end of the tracking session, when I tried to put vibes on the song. I tried every instrument I could, and when I said that, he said, ‘I think we might already have it.’”

The mixing was done by hand in the same room by Coleman and Giraldo. “I took part of the console and he took the other and we rehearsed our moves and just did it,” Giraldo recalls with a chuckle. “Pete was really great at that. He was really fun to work with.”

Looking back, Giraldo laughs at how primitive recording seemed back then, but it had its advantages. “If we would have been making that record today, I would have fixed that 6-bar phrase to feel just like an 8-bar phrase and I maybe would have screwed that all up. It would never have been the same record.”