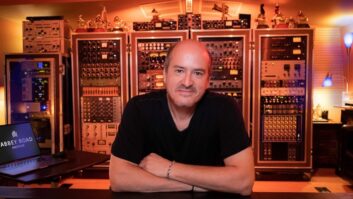

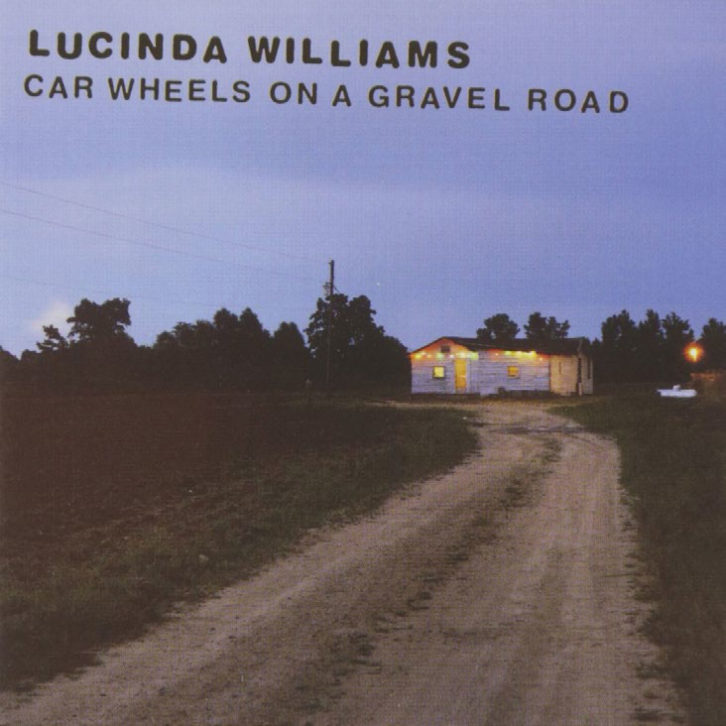

Mixing Lucinda Williams’ Grammy Award–winning Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was much like putting together a big jigsaw puzzle, admits engineer Jim Scott, who was in charge of that process in 1997.

That’s because of the record’s complicated production history, which began in 1995 and included a falling out with her guitarist/co-producer Gurf Morlix, resulting in a re-start of the project with Steve Earle and Ray Kennedy at the helm and a final recording schedule with Ray Bittan in charge.

According to engineer Kennedy, after the initial completed recording was rejected by American Recordings label head Rick Rubin, Williams’ experience singing a duet with Earle at their Nashville Room and Board Studio led to the decision to re-do the album there. Those recordings were finished in a week. (Note that Morlix still recorded guitar on the re-tracked album in Nashville.)

Kennedy says they cut the tracks live, including Williams’ vocals, which was a first for her. The project was recorded on a 1962 Telefunken V76s German tube broadcast desk to an MCI JH16 24-track 2-inch tape machine, then mixed to ½-inch tape.

RE-TRACKING—LIVE IN STUDIO

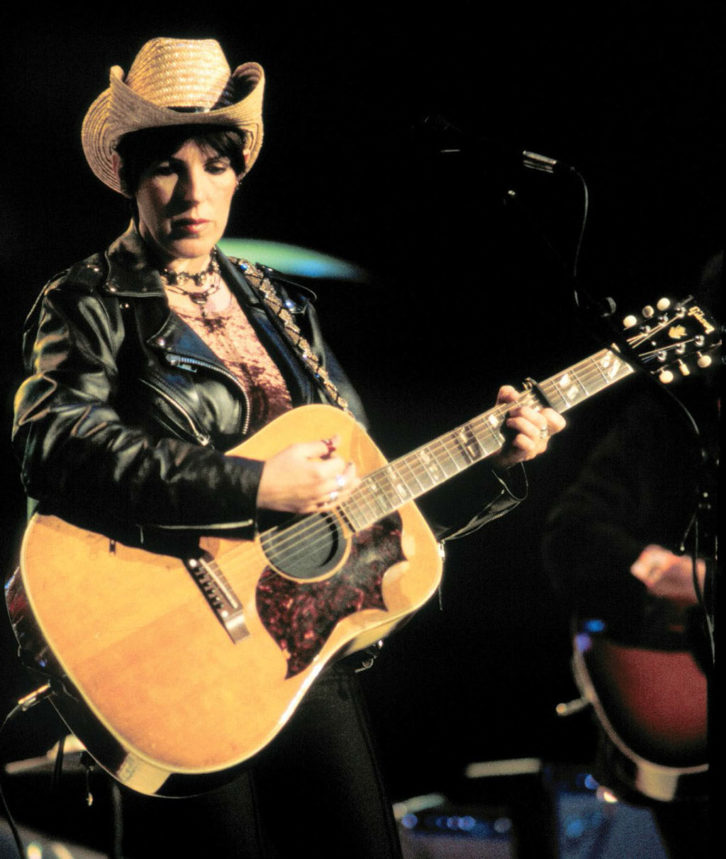

During the first setup day, as he was positioning the Neumann U67, Williams told him he need not spend too much time tweaking it because she’d only be doing scratch vocals. He explained to her if she went full tilt with her vocal, she might inspire the band to perform in a different way.

“I told her, ‘All your favorite records from the past were done that way,’” Kennedy recalls. “Not that they didn’t fix a few things, but the intent was always to perform live. So she said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it. I’ve never been able to do it before, but I’ll do it.’”

And she did. The whole album.

“That’s why it became such a great record—because it was so super-charged with her great vocal, which she had never really tried before,” Kennedy says.

It also had a slightly different drum sound that what was in the air at the time. Kennedy says he attributes some of that sound to the studio’s vintage Leedy drum kit, which drummer Donald Lindley said made him feel more creative.

“I think it gave the record a personality and sound that other records didn’t have because no one else was using a jazz kit from the ‘30s in the ‘90s,” Kennedy says, noting that there were “probably six mics on the 28-inch kick drum,” along with some RCA Varacoustic ribbon mics.

Image By: Tim Mosenfelder/ImageDirect

The record has no reverb whatsoever. Kennedy’s not a fan. In fact, he started a program called Digital Reverbs Anonymous.

“It’s more real [without reverb],” Kennedy asserts. “So Car Wheels on a Gravel Road has no reverb, but it has the natural ambience of rooms. Nobody has ever said, ‘Where’s the reverb?’ Nobody has ever questioned Tom Petty not having reverb on his records.”

Almost everything he recorded, however, did go through UREI 1176 Blackface compressors. “The amount of compression I used was mainly as a tone box,” Kennedy says. “It wasn’t to limit the signal going to tape; it was more about making the sound a little tougher. Anything out in the room, you put a little compression on it and it hears more of the room.”

They also recorded a fair amount of overdubs, Kennedy recalls—acoustic and electric guitars and electric slide, background vocals, keyboards (mainly B-3), and some tambourine.

And then, after a week, Kennedy turned over the tapes to Jim Scott, and he remembers being pleased and grateful with the choice, as he says they are “sonically aligned.”

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

Scott recalls mix sessions taking place at Andora Studios in L.A.’s Cahuenga Pass on “a Neve onsole with two 24-track Studer tape recorders,” and the record arrived with multiple reels of overdubs. All of the live basic tracks ended up on the first tape recorder.

While Rick Rubin left Scott with the choices of which performances or even instruments to use on the tracks, Scott says most of the record “got its bones” from Steve Earle and Ray Kennedy.

“[In those days] you would quickly fill up those 24 tracks with information,” Scott says. “In the analog world, you choose carefully because you don’t have a lot of real estate. I can’t give you ten tracks [to do a vocal]. If you want to try it again, you have to erase something that you just did, and maybe part of it was good, so now what do you do? That’s where the second machine comes in. There was a timecode where you could lock the machines together so they ran at the exact timing and you had more real estate and you could have 24 more tracks to add more overdubs. I think, from my memory, on some songs there was a third reel.”

He describes Williams’ vocal on the title track as a “poetic voice that’s fragile, but she’s like Nancy Pelosi, who with one word can cut your head off.

“It was all done on analog tape,” Scott says. “Pro Tools hadn’t matured yet. No hard drives, no files being sent all over the world, no 100 tracks, no autotune, no tweaking—everything was on tape, so if you liked it, you kept it. If you didn’t like it, you erased it. And if you erased it, it was gone forever and that track went away.

Photo by Zac Caesar

“What did happen, was there was some honor amongst all the thieves,” Scott continues, with a laugh. “On many of the tracks, there was more than one set of overdubs—more than one set of guitars, more than one set of pianos and organs, more than one set of this and that over the same bed track, over the same vocal, Lucinda guitar, bass and drums, the things that went down at the moment when it was birthed and recorded.

“Then different guys got their hands on it. Gurf did some overdubs. Ah, Lucinda hated Gurf; take those off. Well, they didn’t take them off, they just replaced them with something else, so Steve Earle said, ‘Yeah I’ll put guitars on there,’ so Steve Earle played guitar and Ray Kennedy played guitar. And then Roy Bittan is doing it now, and then he’s like, ‘Those aren’t good guitars, I’m going to put some guitars, I’ll put an accordion and mandolin on there.’ So all these tracks existed and nobody had played their guitar to the other guy’s guitar because Lucinda hated that guitar now. I got these tracks, and there are track sheets all over the place and there are two guitar tracks from this guy and two guitars from that guy and piano and organ, and Rick’s no help because he doesn’t care [about the day to day]; he just wants it good.”

So Scott had to go through all the overdubs and put them up against the bass, drums and Williams’ vocal and make some executive decisions: “These sound the best to me. They sound like they’re in the pocket; they sound like they’re in the groove. I like them.”

Scott says he would mix a track and then bring it to Rubin for notes and return to tweak it to his request. He says the biggest challenge was getting the focus right.

“There are some tough, emotional lyrics on there; there are topics so raw and so exposed,” Scott says. “And I’ve been very lucky to work with really great artists where no one really cares whether the tambourine is on 2 and 4 or whether it’s there at all. The details don’t make the record, although they’re very important. The most important thing is the song and the singer.”

His mix approach to the record was minimalist in order to maintain the artist’s integrity. This is especially evident on the title track.

“If you were in a recording studio with a singer like Lucinda Williams and she is singing that song with that voice and playing her guitar, you know what she needs? Nothing. Because she’s Lucinda Williams,” he says.

“So if you’re going to play bass, guitar and drums along with her, you’re going to play like she sings,” he continues. “You’re not going to play like Keith Moon on the drums if Lucinda is singing that song. You’re going to play like she’s singing. That’s why the record was a success as soon as she finished her vocal, whether it was mixed or not. She wrote amazing songs, she had an amazing vocal, it felt good because she’s not listening to a drum machine, she’s not even listening to the drummer. She’s performing her song the way she feels it. Back in the good old days before everything was put on the grid and everything was edited to perfection. These tracks ebb and flow. They speed up and they slow down and they feel good; they hit hard and they relax back and it’s all just part of the vocal. Nothing gets in the way of her.”

One mix—on “Metal Firecracker”—is credited to Kennedy because, while in the mastering process at MasterMix in Nashville (as the 1998 tornedo touched down), Kennedy listened to Scott’s mix and realized Williams had removed Morlix’s vocal and had replaced it with some generic backgrounds.

“I had always thought the background vocal he sang really made the song. It’s kind of a cross-voicing like an Everly Brothers thing,” Kennedy explains. He took Williams out to his car, where he had the original board mix, and played it for her. She agreed. Kennedy furnished the original board mix for mastering.

In summary, Scott’s mix took a couple of weeks, and he says he approached it the way it deserved to be mixed: “Rough and raw, and it sounds honest and humble and rockin. There’s not a lot of tricks and kinda no place to hide, and it’s dry and in your face. It’s like, ‘All right baby, warts and all, Lu, here you go baby, here’s your record.’”