For most of his career up until 1975, Al Stewart considered himself a folk singer, playing in the English folk scene. Most of his songs were historical in nature, the telling of tales a la a modern bard or minstrel. But upon meeting producer/engineer Alan Parsons at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios, he shifted to folk rock.

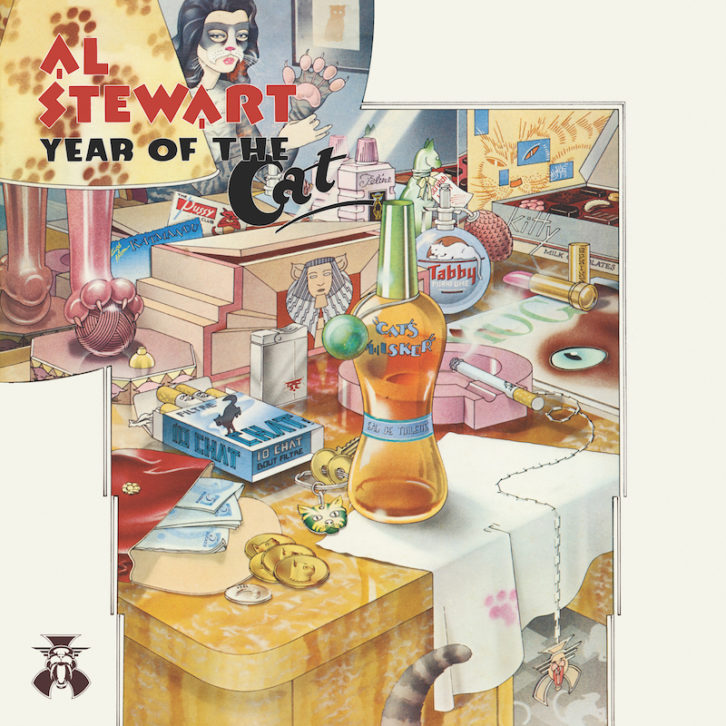

Their second project together generated what became one of Stewart’s signature hits, “Year of the Cat,” the title track of his seventh album, reissued in a glorious 45th anniversary boxed set last year by Esoteric Recordings.

Parsons had joined EMI in 1965 at age 16, working in various departments at the company’s Hayes tape duplication and pressing plants. In the fall of 1968, at age 19, he applied to work at EMI’s studio at Abbey Road, and was hired by studio chief Allen Stagg that October. “Two weeks after that, I was walking up those steps, as I did for many years, from that point on,” he says.

Parsons began, like all freshman engineers at the studio, in the tape library, and then as a tape operator (“second engineer,” officially). He famously was sent, just three months later, to The Beatles’ Apple Studio to op for Glyn Johns for the Get Back sessions. He then moved to “balance engineer”—recording engineer—in 1970 on The Hollies’ “Gasoline Alley Bred” (he later helped craft their first big hit together in 1973, “The Air That I Breathe”), and he continued working with some of the label’s biggest acts, including Paul McCartney & Wings (Wild Life, Red Rose Speedway) and, of course, Pink Floyd (The Dark Side of the Moon), quickly becoming renowned in the recording world for his creativity and skill.

He became a producer in early 1974, co-producing Cockney Rebel’s The Psychomodo with Steve Harley. His base remained EMI’s Abbey Road Studios. “I didn’t work anywhere else,” he says. “It was home to me.” He remained on staff well into the 1990s, even during his mammoth success with his own Alan Parsons Project, which he began during his Stewart projects and continues to this day.

“No one on the folk scene knew anything about production, and I don’t think they even cared,” Stewart notes. “Eventually, though, bands like Steeleye Span and Fairport Convention began paying attention to production, and their records sounded noticeably better.”

NEW PRODUCER, NEW SOUND

So by 1974, Stewart began thinking of a new producer for what would become Modern Times. “The introduction came from a tech guy at Abbey Road, Seumas Ewens, who did tape copying— but was also very into folk-rock music,” Parsons explains. “I jumped at the chance.”

Modern Times was recorded in October 1974, followed by sessions in mid-September 1975 for what would become “Year of the Cat.” The musicians for both included the rhythm section of Cockney Rebel—George Ford on bass and Stewart Elliot on drums. Versatile session guitarist Tim Renwick had played on Stewart’s previous two records with producer John Anthony, 1972’s Orange and 1973’s Past, Present and Future. Piano was played by Peter Wood (with some tracks by Don Lobster). Peter White was also hired as a keyboardist, but ended up playing guitar, as well, most notably the Spanish guitar solo on one of the album’s hit singles, “On the Border.” He continues to play gigs with Stewart and Parsons to this day.

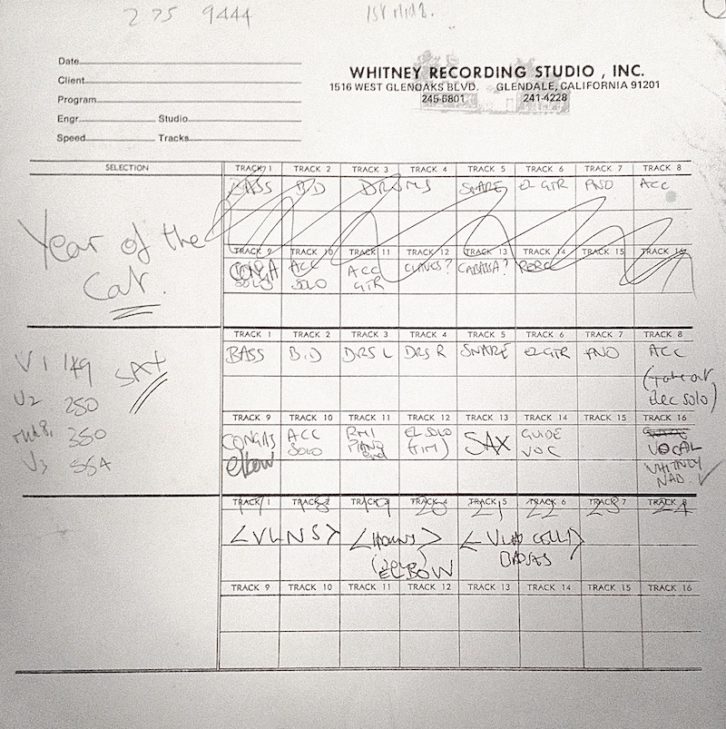

The team recorded in Studio 3, where the control room had been upgraded from one of EMI’s own “TG” desks to an EMI Neve, a 1086 console. The tape machine was a 16-track Studer running EMITAPE, though by the time the group returned to the studio in June 1976 to record string overdubs, as well as a new track, “On the Border,” the studio had upgraded to 24-track Studers.

Stewart would play an Epiphone Texan acoustic guitar, set up in Room 43, the former/original control room for Studio 3, miked with a Neumann KM84. On occasion, White would join him. “Al just really strummed chords, which is still how he plays today,” Parsons recalls. Elliot’s Ludwig kit was set up against the center of the left-hand wall, facing into the room.

Parsons’s drum miking in those days consisted of an AKG D20 on the kick and a Neumann U87 on the snare, top only. Track sheets show two other tracks, which he used either for toms or overheads. “I probably would have had close mics on the toms, either AKG D19 or D190Es,” he says. “But if I was happy with the overhead mics, then it would just be the overheads on those two tracks,” for which he would use STC 4038s.

Renwick played his Strat through a vintage cream-colored, single-speaker Fender amp, set up in front of Elliot’s kit and isolated with a U-shaped pair of gobos. Ford’s bass was recorded through a DI box.

Classic Tracks: “Summertime Blues”

Stewart didn’t prepare any kind of demo recordings. “The band would be booked, and he would just play the song on his guitar, shouting out the chords if they were in question,” Parsons explains. “Everybody got to hear it for the first time, there.”

Stewart would then work directly with Renwick on the guitar solos, which were key to the recordings. “When it’s time for a guitar solo, I like to have it over a completely different set of chords than the verse or chorus,” Stewart explains. “I would just sit down with Tim, and if the song was in C, I would just play B flat, to see what happened. Then we’d have this completely random set of chords. And Tim would make a solo out of it, and we’d put it into the song.”

And the lyrics? Uh…what lyrics? There weren’t any. “That was my process,” the artist states. “I did everything backwards. I would go in, record all the backing tracks, without really knowing what the song was going to be about. We recorded all the music for ‘Year of the Cat,’ and then they let me loose for a couple of months, and I just wrote bags of lyrics. Maybe three or four different sets of lyrics. I would just prune it and keep the best bits.” While tracking, he would simply give a good “La la la,” or improvise a rhyme in real time, based on nonsense.

MUSIC, MEET LYRICS

The music for “Year of the Cat” came about from a riff Peter Wood would play during soundcheck while the band was on tour with Linda Ronstadt in 1975, supporting Modern Times. “After I’d heard the riff a dozen times, I said, ‘You know, that’s very catchy. I like that riff. Maybe I could write some lyrics to it,’” Stewart recalls, “and he said, ‘No. It’s an instrumental.’ But, of course, I ignored him. But I also told him, ‘You can play a minute on solo piano before the song comes in.’ So that’s exactly what we did.”

Stewart’s lyrics actually began as “Foot of the Stage,” a song about the late English comedian Tony Hancock, who had taken his own life. The label had no interest, as American fans had no idea who Hancock was.

Meanwhile, Stewart’s girlfriend at the time had a book on Vietnamese astrology. “It had a chapter in it called ‘The Year of the Cat.’ And I thought, ‘Well, that really sounds like a song title.’” Stewart says. “But, of course, I can’t write it about Vietnamese astrology. So I just turned it into a North African love song.”

The backing track, which had been recorded with the others in September 1975, likely features Stewart on acoustic, according to Parsons, though he thinks it was Renwick due to the presence of a difficult chord.

The song originally would have had four solos—strings plus two acoustics and one electric—but “it had too many solos in it,” the producer explains. “I said, ‘How about a saxophone?’” Stewart objected, noting, “I’m doing folk rock. There are no saxophones in folk rock,” suggesting bagpipes instead.

Eventually, Parsons talked him into letting him give it a try and suggested a player, Phil Kenzie, who lived 10 minutes away. “Alan called him, but he was watching a movie and said he wanted to see the end of it,” Stewart recalls. Parsons persuaded him that he could perform the part quickly on alto sax, in Studio 2, in time to get back to see the end of his movie, which he did.

VOCALS AND MIXING

Between Parsons’ own projects (including the first Alan Parsons Project sessions) and Stewart’s lyric writing, it wasn’t until April 1976 that work resumed on the album, this time in Los Angeles. The original 16-track masters were transferred to 24-track at Kendun Recorders in Glendale, and then Stewart recorded his vocals at Whitney Recording Studio, also in Glendale, typically getting in two songs per day.

Stewart sang in his unique soft tone, something that he came upon in his first band when he was 17. “My voice was just really soft,” he explains, “and it was kind of fey, and I didn’t like it at all. What most people don’t know is that I’m not really singing. I don’t linger on any of the notes, because I really can’t sing. If I try to hold on a note for a couple of seconds, it would waver in pitch and go off key.”

String overdubs—arranged by Andrew Powell, whom Parsons had met via Steve Harley of Cockney Rebel—were added on a return trip to England in June, in Abbey Road Studio 2. “After the end of 1974, I really didn’t work with any other arranger other than Andrew,” Parsons notes.

His miking setup for strings at the time provided for a mic for every player. “Most people would just mike a whole section—first violin, second violins, violas, cellos and basses,” he notes, “but I preferred to have one mic at every music stand. It improved separation.”

Final mixing—as well as additional lead vocal recording—took place on a return trip to L.A. in August, at Davlen Sound Studios in Universal City. For reverbs, he used an EMT 140 plate, with a tape delay ahead of the plate in the signal chain. “Pre-delay is a piece of cake now, which you can simply set,” he says, “but it was likely an Ampex or a Studer machine, just constantly running.”

Final side assemblies were made by Parsons at Davlen on August 16. The album was issued two months later on Janus Records, in early October, with the single coming at the end of November. The combination of Stewart’s thoughtful lyrics and melody, his smooth vocal delivery style, and, of course, Phil Kenzie’s saxophone solo, all but guaranteed its success.

Regarding the latter and its presence on this folk rock track, Stewart notes, “Of course, I was completely wrong about it. Just listen to Paul Simon’s ‘Still Crazy’ or Gerry Rafferty’s ‘Baker Street.’ So the answer is, yes, there can be saxophones on folk rock. If I’d had my own way, there probably would have been bagpipes on it! Of course, the record comes out and the only thing anyone talked about was the sax solo. If I’d been adamant, refused to have it, it probably wouldn’t have been a hit.”