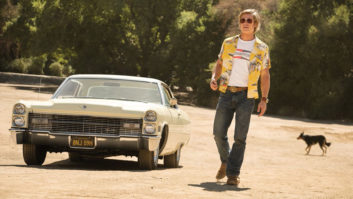

Photo: Mark Selger

“Lenny Kravitz has taken up 80 percent of my adult life,” says engineer Henry Hirsch without so much as a trace of cynicism in his voice. “When I met him, he was exactly as he is now; there’s not much different about what he is.”

Hirsch met the singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist/producer almost 20 years ago when Kravitz walked into Hirsch’s Waterfront Studio, then in Hoboken, N.J., to cut a demo with his band. As it turned out, the teenaged Kravitz was the only one qualified for session work and he ended up playing most of the instruments — the beginning of a recording method that would come to define his career. Although the two men connected, for Hirsch it was just another session. But when Kravitz signed his record deal several years later and was ready to cut his debut album, Let Love Rule, he remembered the engineer that he calls “the best in the world.” They’ve been partners ever since, and their collaborative efforts are most recently heard on Kravitz’s latest release, Baptism.

Like his previous recordings, Baptism showcases Kravitz’s myriad influences, ranging from classic soul to contemporary rock. One moment he’s unleashing wild guitar solos and the next he’s singing the blues. His fondness for what Hirsch calls “real instruments,” however, has earned him a retro tag, which the engineer finds offensive. “Lenny’s style and sound don’t fit current trends,” says Hirsch. “Listen to his first two records compared to other records made in the late 1980s, like MÖtley Crüe, and see which sounds more dated. The retro tag stuck and has not been helped by the vintage gear I have. We’ve done what we wanted to do, and, unfortunately, he’s been hit hard and I take exception to it.

“My role is completely in recording and interpretation,” Hirsch continues on a lighter note. “Lenny comes forward with a song and I make it into something we both want to hear. I take his raw ideas and we build it up. We don’t have a band. We take it from the bottom up, drums or whatever instrument, and I envision what it should sound like when it’s finished. If the drums are wrong, it shows when we do guitars. He gives me a basic idea and trusts me to make the right decisions. Vocals are cut at the end of the recording process and all that we’ve done before that has got to make musical sense. Sometimes it does and sometimes it’s a struggle.”

Henry Hirsch and Lenny Kravitz in the studio

Photo: Philip Andelman

“Henry helps me come up with the sounds I’m looking for,” says Kravitz. “He understands when I say I want the drums ‘carpet-y’ or ‘boxy,’ or I want the guitar to be like this or like that. He understands the references. He also gives me his opinion.”

“I can overstep,” Hirsch admits. “Sometimes he completely wants to throw me around the room, and sometimes it gets volatile, but it would be a disservice not to give him my true opinion, whether it’s good or bad. We fight. It’s what it is, and usually he’ll say, ‘You don’t get it,’ but I’m persistent, and if I don’t like it, I don’t play it. He’ll say, ‘Put the guitar in.’ ‘What guitar?’ ‘The damn guitar!’ ‘Oh, that thing? We have to listen to this?’ ‘It sounds great!’ So I get about 10 percent and he gets 90 percent.

“We’ve had, from the beginning, a communication and musical point of view that doesn’t even have to be spoken,” Hirsch continues. “When he starts a song, he leaves me to do the audio and I leave him to do his thing. The partnership stands up because of a mutual love for each other. We communicate easily without saying much.”

Kravitz wrote, produced, arranged and performed all of the material on Baptism. Hirsch played bass and piano on two tracks; their partner, David Baron, played sax on one track and arranged strings with Kravitz on another. Bandmember Craig Ross added guitars, drums and piano. The album was recorded in Miami at Kravitz’s Roxie Studios, and in New York at Edison Studios. Engineer Cyrille Taillandier handled the Pro Tools rig.

“My Pro Tools skills are as low as they can get,” says Hirsch. “Cyrille is very conscientious, and any person manning a Pro Tools station needs to be. This brings up the subject of recording with multitrack tape machines and Pro Tools. It’s an interesting situation because I try to use both. Pro Tools has given Lenny a lot of advantages because it happens so fast and it can fix everything. But I don’t always like everything to be perfect. I like the way multitrack sounds. I like it as a recording machine and Pro Tools as an editing machine, but Lenny often works very fast and Pro Tools does that better than multitrack.”

“I still love tape and the sound of tape and the stereo image of tape, but the new Pro Tools is close,” says Kravitz. “Put something from Let Love Rule on the monitor and something from Lenny on the monitor — the stereo imagery is much different, the new system is wider. So we use it, it makes things go quicker than 16-track 3Ms — it goes cha-clink, and you go crazy punching and editing all day. So I’m kind of stuck on Pro Tools right now as a tape machine and editing machine. Every now and again, we use a compressor or EQ or reverb on it, but not too much.”

Perhaps the most surprising element of Baptism is its lack of effects while sounding as if Kravitz and Hirsch utilized every trick in the book. “The effects are pretty organic,” says Kravitz. “The flange is tape flange; it’s Henry with three tape machines. The slap is tape. Reverbs, 99 percent of the time, are plates. I love when everything is dry and it’s me and a [Neumann] 47 into a Fairchild on the vocals. People aren’t used to hearing nothing, so nothing becomes an effect — dry and compressed.”

“Lenny has a great ear, and the two of us get to a balancing point,” Hirsch adds. “We mix as we make the record. It’s a fundamentally different approach that happens to work for us.

“I do different combinations of things with the drums, and if they’re deadened down, I have no problem doing a traditional miking situation. I make sure it’s all phase- coherent.

“For the bass, I use a custom DI that Dave Amels, a brilliant electrical engineer, built for my specific needs. It’s an amazing design.”

Hirsch continues, “I don’t believe in surrounding myself with a lot of equipment. I don’t record 48 or 64 tracks. I use a Helios console, an English console built by the people who built Olympic Studios in the 1960s. It has 26 inputs, eight groups and 24 monitors. The beauty is the simplicity — very little electronics. I believe the less electronics, the cleaner the sound. This being at odds with most console manufacturers who cater to people who like things that look big.

“I use ATC SCM200s for monitors. They’re English speakers. I knew immediately that they were what I was looking for because I’m always struggling with midrange in loudspeakers. These SCM200s were set up by Ross Alexander, an engineer from Miami who retuned the entire studio, as well. They’re beautiful-sounding monitor speakers, the frontline of sound here.

“Dave [Amels] built me custom mic pre’s. My criteria was a mic pre with very little distortion. “I also have a Fairchild 660 compressor. It’s the first piece a vocal will hit; it’s very nondestructive. To limit the vocal, I use a Focusrite 230. We also use a Motown EQ. It’s a hard-to-find gentle EQ.”

Regarding mics, Hirsch’s first choice is the Neumann U47. “I’ve been recording Lenny with those for at least 10 years. It’s his frontline mic. I also use the 269, a version of the [Neumann] 67. I have four RCA 10001s — very rare mics that I learned about from Keith Grant, who built Olympic Studios. I have a BBC [Coles] 4038 [ribbon mic] and a Sanken CU-31 to give extended high end. I have two AKG C28s [tube mics] on my piano and a Neumann U57 that’s not well known, but it’s a good mic orchestrally. I use a Sony C38 for guitars, amps and anything loud because it simply will not distort.”

It’s not always easy working with, or being, a one-man band in the studio. Kravitz — an obvious perfectionist — admits to being his own worst critic, noting, “If I’m not feeling something, I’m not like, ‘Oh, that’s wonderful, I did it.’ Not at all. I’ll work on something and work on it and work on it until I get it right or it doesn’t happen. [I’ll] work on the same piece, changing the drums, doing things one at a time. I don’t have the luxury of a band getting things worked out. You have snare, you put guitar on top, now the snare’s not so big, the kick gets lost from meshing with the frequency of the bass, or maybe some of the low mids on the guitar are crossing it and that’s when we run into nightmares. Not often, but it happens. Then it’s, ‘Let’s recut the drums.’ ‘Oh, it’s not quite as good.’ ‘Oh, I love the drums now, but the guitars don’t work; let’s do it again.’ This can go back and forth for two weeks. It’s a frequency dance you’re doing, and with a band, I’d be able to work it all out, but that’s not the way it happens with me.”

“It has its upsides and downsides,” says Hirsch of the process. “The downside is you don’t know in advance what the finished record will be. With a band, you have a dummy vocal and a clearer framing of the song. The advantage is that Lenny plays all the instruments so well that he assists in my work, sound-wise. I have a better chance to get a good sound from the drum kit, for example, because he’s sympathetic to how it should sound.”

The creative process for Kravitz is different for every song. “Sometimes, I take the track home and write lyrics,” he says. “Most of the time, I cut drums, guitar or piano, bass, more guitar and then vocals. Lyrically, it just comes out. A lot of times, I cut a track, hear the melody and write lyrics. That’s what this record is about — I don’t have a concept or direction. I stay out of the way and just let it happen.”

“Lenny is a musical genius,” says Hirsch. “People don’t give him the credit because they think it’s his group, but 90 percent is him playing stuff from the bottom up. His style, which is just what he does, is a combination no one really has today of older R&B and a sense of rhythm and rock ‘n’ roll, which is why he’s so unique. As a singer, he’s gotten better and better and better.”

Kravitz is equally quick to praise Hirsch and credits him with successfully translating ideas and sounds to disc. “Henry is brilliant,” he says. “He writes, plays and understands music. He’s extreme with his engineering. He chains things together, goes in and out of channels and has such an amazing ear. When we mix, we share such a similar sense of balance and placement. He’s technical as well, and understands signal flow, how to get stereo image at its best, understands EQ like no one I’ve ever seen. I can’t say enough good things about him. It’s a blessing to have him in my art.”