Time to gear up for the Academy Awards on February 9, not to mention the MPSE Golden Reels and CAS Awards in late January. With so many fantastic films in 2019, narrowing down a list of sonic favorites was no easy task. But the worst decision is indecision, so here you go—our top picks for sound mixing, sound editing and composing an original score. With a nod to the creators and a bit of commentary thrown in.

Note: This post has been updated to include Production Mixers for each film. Mix apologizes for originally omitting this important first step in the film sound process.

SOUND MIXING

Joker

Rooting for the bad guy may send the moral compass spinning, but it’s hard not to feel compassion for sad-clown Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) in Joker—even though you know he’s a complete psycho. It leaves one with a conflicted, uncomfortable feeling that’s bolstered by the oppressive, intrusive sound of Gotham City, crafted by supervising sound editor Alan Murray and re-recording mixers Tom Ozanich and Dean Zupancic at Warner Bros. Sound.

City sounds infiltrate the intimate moments of Arthur’s life. Car horns disrupt the strained session between Arthur and his social worker as she reviews the questionable contents of his journal. An angry neighbor yells through the wall into Arthur’s apartment as he’s having an emotional breakdown. He can’t escape the city, his situation or himself.

The world of Joker feels alive, made tangible by distinct sonic details—like individual pedestrian voices passing by on the street, the contents rattling in the overhead luggage rack on the city bus, and the rhythmic buzzing of a broken light in the public restroom—which are discretely placed around the Dolby Atmos surround field.

Ozanich, who mixed dialog/music, even used the Atmos setup to create multifaceted reverbs that simultaneously define the space on-screen and pull it out into the theater by combining multiple reverbs and EQs to create the processing on a single sound event, so you feel like you’re in the room with the characters. So, for instance, when Arthur is waiting in the green room before his appearance on the Murray Franklin Show, you hear voices slapping off the hallway walls and filtering through the door (played through the front speakers) and then reflecting off the walls around him (played in the surrounds).

“I think a lot about the geography of what is happening and then the physics of what is happening, and try to factor all of those things together to decide how a thing would sound if I were standing right there,” explains Ozanich. This results in incredibly real and alive spaces that completely immerse the audience.

Director: Todd Phillips. Movie Studios: Warner Bros. Pictures. Re-Recording Mixers: Tom Ozanich, Dean A. Zupancic. Supervising Sound Editor: Alan Robert Murray. Foley: Dan O’Connell, artist, John T. Cucci, artist, Richard Duarte, Foley mixer. Composer: Hildur Guðnadóttir. Supervising Music Editor: Jason Ruder. Production Mixer: Tod A. Maitland CAS.

The Aeronauts

In 1862, traveling to 36,000 feet above the ground might as well have been traveling to the moon. It was an unthinkable height with unknowable dangers. The Aeronauts protagonists—balloon pilot Amelia Wren (Felicity Jones) and meteorologist James Glaisher (Eddie Redmayne)—are caught unprepared for the conditions at that altitude, lacking warm clothing and an oxygen supply.

If ever there were a film made for Dolby Atmos, it’s The Aeronauts. Above the characters is a gigantic gas balloon surrounded by a network of ropes, the sound for which lives in the overhead speakers. Scientific instruments clatter and flags flap at various pinpointed positions in the surrounds. The creak of the balloon’s wicker basket emanates from the front wall. And individual gusts of wind (whistling, wispy or buffeting quietly), constructed in multiple layers, are constantly moving along their own complex paths through the Atmos soundfield as the balloon rises through various wind currents.

“The complexity of these layers creates a subliminal sense of movement and tells the story of their continuous ascent,” says re-recording mixer/supervising sound editor Lee Walpole at Boom Post.

Before the storm, the balloon emerges from a thick fog in which all sound felt swallowed and dull. As the weather begins to change, thunder sounds in the distance and the wind picks up. What was once oppressively quiet begins to grow steadily noisier. “When we have the first big gust of wind wafting across the room, you hear the cause and effect that wind has on the other sounds—the balloon, the ropes and the scientific instruments,” says Walpole. “I spent a considerable amount of time on sound placement in this section, trying to locate the viewer into the balloon basket and give them a sense of the storm coming at them from all sides.”

Director: Tom Harper. Movie Studios: Amazon Studios. Re-Recording Mixers: Lee Walpole, Stuart Hilliker. Supervising Sound Editor: Lee Walpole. Sound Designer: Andy Kennedy. Foley: Anna Wright, artist/editor, Catherine Thomas, artist, Sarah Elisa, Foley editor, Philip Clements, Foley mixer. Composer: Steven Price. Music Editor: Bradley Farmer. Production Mixer: Tom Williams.

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

The Star Wars saga that George Lucas originally envisioned is wrapping up this holiday season with the ninth installment, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The generation-spanning epic space adventure has brought cinematic joy to three generations—my parents had their trilogy back in the late ’70s/early ’80s. My generation had ours in the late ’90s/early 2000s. And my kids are experiencing their trilogy now. The first musical theme my youngest daughter ever hummed was that of Darth Vader from John Williams’ “The Imperial March.” She even dressed as a stormtrooper for Halloween one year. And all I could think was, “Aren’t you a little short for a stormtrooper?”

Star Wars was the progenitor of Skywalker Sound; when director Lucas teamed up with sound designer Ben Burtt, they forever changed the course of film sound, both creatively and technologically. Star Wars isn’t just a great story; it’s an industry-altering force that propels progress at every level of the filmmaking process.

As with any Star Wars film, The Rise of Skywalker will be a feast for the ears, with the promise of a massive space battle with complicated aerial maneuvers, an action-packed chase sequence or two (or three), and a light saber duel played out in a dramatic setting.

Skywalker Sound re-recording mixer Christopher Scarabosio (effects/Foley/backgrounds) and re-recording mixer Andy Nelson (dialog/music) are back on board for The Rise of Skywalker. Their mix on The Force Awakens earned them a 2016 Oscar nomination, and Scarabosio earned another nom for the mix on Rogue One in 2017 (shared with Oscar-winning re-recording mixer David Parker). Regarding their mix on The Rise of Skywalker, Scarabosio says, “We wanted to make a track that was as epic as the saga itself.”

Director: J.J. Abrams. Movie Studios: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. Re-Recording Mixers: Christopher Scarabosio, Andy Nelson. Supervising Sound Editor: David Acord, Matthew Wood. Sound Designer: David Acord, Ben Burtt. Sound Effects Editors: Justin Doyle, Addison Teague. Composer: John Williams. Supervising Music Editor: Ramiro Belgardt. Production Mixer: Stuart Wilson.

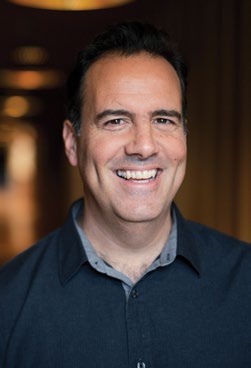

The Irishman

Director Martin Scorsese just made the mob film we’ve been waiting for: The Irishman. The cast is a master list of crime film favorites: Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Harvey Keitel, Bobby Cannavale, Stephen Graham, Ray Romano, Jesse Plemons and Paul Herman, among many others.

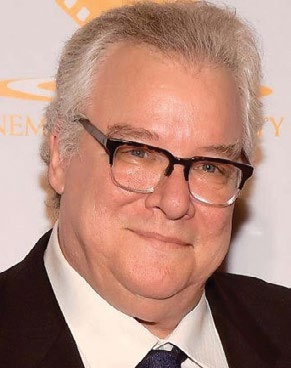

And the soundtrack is as understated as a mob boss nod. It’s not showy or overt; it doesn’t have to shout. Instead, it quietly demands respect and definitely deserves Oscar recognition. “Marty and Thelma [Schoonmaker, picture editor] were very clear about keeping the track as quiet and restrained as possible, particularly in the key interior scenes,” says Oscar-winning re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman from Soundtrack New York; Fleischman will receive a CAS Career Achievement Award at the Cinema Audio Society’s 56th annual ceremony on January 25.

Fleischman handled dialog/music while re-recording mixer/supervising sound editor Eugene Gearty mixed effects. Fleischman and Gearty both won Oscars for their work on Scorsese’s Hugo in 2012.

Fleischman’s focus on The Irishman was to “keep the dialog clear and the voices natural, with no off-screen distractions,” he explains.

The measured conversations between two or three characters in quiet environments proved the most challenging for Fleischman, like the prison scene in which Hoffa (Pacino) and Tony Pro (Graham) discuss union pensions, a later meeting between Hoffa and Tony Pro in Florida, and a breakfast scene in a Howard Johnson’s hotel where Frank (De Niro) and Russell (Pesci) talk about Frank’s trip to Detroit to take out Hoffa. Fleischman contends that these “are the most difficult kinds of scenes to mix because there is nothing to hide the manipulation of the track and the changes in tone from shot to shot. This was especially true here because we were adding so little background effects.”

Even though The Irishman was mixed in Dolby Atmos, Fleischman notes they used the format sparingly, with the Jerry Vale performance at Frank’s union appreciation dinner being the biggest Atmos moment. “Marty was very concerned about making the Jerry Vale songs seem natural to the room. Jennifer Dunnington, our wonderful music editor, worked very hard on the lip sync, and I used some interesting reverb and Atmos effects to fit it into the scene so that it played naturally,” says Fleischman.

He admits, “The Irishman is perhaps the most sparse and restrained mix that I’ve done, and it’s a very long film, so it was like mixing two movies in one. I loved that it is not a big, loud, flashy mix; its restrained quality serves the story so well that it has drawn a great deal of attention. I am very proud of my work on this film.”

Director: Martin Scorsese. Movie Studios: Netflix. Re-Recording Mixers: Tom Fleischman, CAS, Eugene Gearty. Supervising Sound Editor: Philip Stockton, Eugene Gearty. Foley: Marko Costanzo, artist, George A. Lara, CAS, Foley Mixer. Composer: Robbie Robertson. Music Editor: Jennifer Dunnington. Production Mixer: Tod A. Maitland CAS.

Rocketman

Rocketman isn’t a cut-and-dry musical biography. It’s an interpretation of Elton John’s rise to fame, told through flashbacks and memories recounted by Elton (Taron Egerton) as he wrestles with sobriety in a support group meeting. It turns out to be the perfect storytelling device, allowing director Dexter Fletcher to freely mix fantasy, reality, music and emotion in a way that would best represent a man who isn’t afraid to walk around in platform shoes wearing sparkly star-shaped eyeglasses.

Actor Egerton sang every song in the movie, both in the studio as prerecorded material for playback and on-set as part of his performance. Rerecording mixer Mike Prestwood Smith, who handled dialog/music, had the goal of making all the songs feel as though Egerton were singing in that moment. This would have been impossible for Egerton to do physically, of course, particularly for the “Rocketman” song in which Elton is sinking to the bottom of a pool.

Nevertheless, Smith manages quite well to make the singing seem believable. There is a scene in which Elton is sitting backstage at Madison Square Garden wearing a feathered and sequined devil costume. He stares at his reflection in the mirror and quietly starts to sing “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.” The performance is more like dialog, in that it’s intimate and unpolished, like he’s singing to himself. This onset performance continues as the music slowly builds underneath. Elton gets up and takes off down the corridor and his voice reverberates off the walls. You don’t know if it’s still on-set performance or studio performance. It feels real, in that space and in that moment. By the time Elton jumps into the backseat of a taxi, the music is a full-on studio recorded song.

“Once you’re into the track, you have the audience there,” says Prestwood Smith. “But getting in and out is hard. The filmmakers want the audience to believe what they’re seeing, that Taron was actually in these situations surrounded by a certain level of reality at any given point, even though it’s a fantasy.”

Prestewood Smith (who earned an Oscar nom in 2014 for his mix on Captain Phillips) worked alongside supervising sound editor Matthew Collinge, who was also the re-recording mixer on effects.

Director: Dexter Fletcher. Movie Studios: Paramount Pictures. Re-Recording Mixers: Mike Prestwood Smith, Matthew Collinge. Supervising Sound Editor: Matthew Collinge. Foley: Peter Burgis, artist, Zoe Freed, artist, Glen Gathard, Foley Mixer. Composer: Matthew Margeson. Music Supervisor: Ian Neil. Production Mixer: John Hayes.

EDITING

Avengers: Endgame

Never in my movie-going experience has an audience had such a vociferous reaction to a film as they did on Avengers: Endgame. When Captain Marvel (Brie Larson) showed up to do battle, people were literally yelling encouragements at the screen.

At this point in the Avengers franchise, each superhero has established signature sounds that need to be carried forward and expanded to fit the requirements of a particular film. And Avengers: Endgame is a glorious parade of Marvel superheroes. The massive battle in Endgame is a culmination of 22 films worth of signature sounds. Also, Endgame jumps back in time to scenes from other Marvel films.

Those sounds and scenes needed to be faithfully reproduced, and if anyone is equipped for that mind-blowing task, it is Skywalker Sound supervising sound editor Shannon Mills. He’s worked on many (nearly all) of the Marvel films and has been “keeping a log and a live version of all 22 films because you never know when someone is going to show up in a Marvel film you’re working on,” he states.

Lucky for Mills he wasn’t working alone: “I have an excellent team and we had done a lot of the sounds together. We had Samson Neslund, Nia Hansen, Josh Gold and Steve Orlando on the sound effects side. They were instrumental in helping to find those moments that we needed.”

Another thing to note about the sound design on Endgame is the massive scale of destruction that happens during the final showdown. Thanos (Josh Brolin) is raining down thousands of missiles that are blowing up everything. Then Captain Marvel flies in and destroys the attack ship. It’s truly epic, and getting the sound to match something of that scale is challenging.

“A lot of credit goes to re-recording mixer Juan Peralta,” says Mills. “He’s really great at getting scale and size to match what’s on-screen. Working with Juan, working with the subwoofer, and also trying to get quiet right before a big event gets us a lot of mileage.”

Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo. Movie Studios: Disney/Marvel. Re-Recording Mixers: Juan Peralta, Tom Johnson. Supervising Sound Editor: Shannon Mills, Daniel Laurie. Sound Designer: Shannon Mills, David Farmer, Nia Hansen. Sound Effects Editors: Samson Neslund, Nia Hansen, Josh Gold, Steve Orlando. Foley Supervisor: Christopher Flick. Composer: Alan Silvestri. Score supervisor/supervising music editor: Steve Durkee. Production Mixer: John Pritchett.

Apollo 11

The first Academy Award for Best Sound Editing (or similarly named categories like Best Sound Effects or Sound Effects Editing) was presented in 1963. Since that time, many films dramatizing historical events have earned Best Sound Editing Oscar noms. But there has never been a documentary film nominated in the Best Sound Editing category. Could Neon/CNN Films’ Apollo 11 be the first?

Apollo 11 is a marvel of documentary filmmaking. Director/editor Todd Douglas Miller’s request for Apollo 11 mission audio/visual material resulted in the discovery of never-before-seen footage of the launch, inside of Mission Control, the capsule recovery and post-mission activities. Plus, more than 11,000 hours of Mission Control audio was found.

All of the footage was MOS (without sound), and the Mission Control voices were just recordings, not synced to anything. The challenge was to clean up the audio and then figure out how it fit together with the footage. Additionally, sound designer/re-recording mixer Eric Milano at The Love Loft in NYC needed to locate and/or re-create sound for whatever was missing, like the Saturn V rocket ignition and liftoff.

Milano found actual ignition and liftoff sounds recorded by people who were at the 1969 launch and used those to re-create the event for the documentary. He consulted with Neil Armstrong’s son to make sure the sound was just right. “Neil’s son remembered this crackling, popcorn sound that was happening after the initial blast off. It almost sounds like distortion. But it’s not. That’s actually how it sounded. That popcorn sound was in some of the recordings, and so we tried to emphasize that,” Milano says.

Additionally, Milano needed to add in all the other details, large and small—ambient sounds, crowds, P.A. systems, helicopters, wind, heavy machinery like the crawler that transports the rocket to the launch pad, computers, cars, planes, oceans, aircraft carriers, footsteps, applause…you name it! And everything had to be as accurate as possible.

For instance, using info from NASA spacecraft manuals, Milano was able to re-create the sound of the 1201 and 1202 alarms that occur during the lunar landing. And he designed the sound of the astronauts’ cassette player spinning and floating around the space capsule, playing John Stewart’s “Mother Country” on their trip home. “There was literally no sound with any of the visuals. Every single thing that we wanted to hear to bring the film to life had to be re-created,” attests Milano.

Director: Todd Douglas Miller. Movie Studios: Neon/CNN Films. Re-Recording Mixers: Eric Milano. Sound Designer: Eric Milano. Composer: Matt Morton. Production Mixer: None.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood

Apollo 11 re-created the ’60s in a historically accurate way, but in director Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, supervising sound editor/sound designer Wylie Stateman at Twenty Four Seven Sound was tasked with re-creating the past in a nostalgic way.

Tarantino’s reverence for late ’60s culture is evident in many of his films, but those were mere references. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood embodies the era with re-created WKHJ radio broadcasts and advertising jingles for products like suntan lotion. Stateman notes that the radio stations and jingles of that era are as iconic as the hit songs of the day. They meant so much to Tarantino that he “personally scoured archives and found the kinds of radio elements that he thought would piece together the period.

“Ninety-nine percent of the radio broadcasts were original. Quentin prides himself on taking the time and making the effort to get that right,” says Stateman, who has been Tarantino’s go-to for sound since Kill Bill: Vol 1. Of Stateman’s eight Oscar nominations, two were earned on Tarantino films—Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood also features classic cars of the day. Stateman and his sound crew recorded eight of the film’s cars, including Rick’s Cadillac Coup De Ville, Cliff’s Volkswagen Karmann Ghia, Jay Sebring’s Porsche 911, Roman Polanski’s MG TD, Charlie’s “Twinkie” delivery truck, and the Ford Galaxy “creepy crawler” car driven by members of the Manson family. With these recordings, Stateman could precisely match the perspective of Tarantino’s shots.

These two elements come together beautifully in one scene, giving the audience the feeling of riding in a car down the streets of Hollywood while listening to the radio in 1969.

Other highlights of sound editing were: replacing the announcer voice saying “Burt Reynolds” with “Rick Dalton” for the recreated TV episode of F.B.I., the montage of neon light buzzes, the Manson family murder scene, and all the period films (like The Great Escape) or invented films (like The 14 Fists of McCluskey and Operazione Dyn-o-mite!) starring Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio).

Director: Quentin Tarantino. Movie Studios: Sony Pictures. Re-Recording Mixers: Michael Minkler, Christian Minkler. Supervising Sound Editor: Wylie Stateman. Sound Designer: Harry Cohen, Leo Marcil, Sylvain Lasseur. Foley: Gary A. Hecker, supervising Foley Artist, Rick Owens, artist, Kyle Rochlin, Foley mixer. Music Supervisor: Mary Ramos. Music Editor: Jim Schultz. Production Mixer: Mark Ulano, CAS.

Ford v Ferrari

The engine sounds in Ford v Ferrari are as handcrafted as the actual Ford GT40 Mk II that won Le Mans in 1966. Sound recordists John Fasal and Eric Potter and sound designer Jay Wilkinson captured all the engine sounds for the film—including a GT40 427 V8 engine used to build Ken Miles’ car in the film’s final race—then Wilkinson and supervising sound editor Donald Sylvester at 20th Century Fox Studios pieced together the engine recordings to match the action on-screen.

They cut multiple tracks of different interior and exterior perspectives, like the exhaust, transmission housing, engine compartment and tires. “Then Dave [Giammarco, re-recording mixer] put it all together on the dub stage to make it sound individualistic, so we could tell the individual engines apart,” says Sylvester. “When there were multiple cars in the scene, Dave would feature one car over the other. This was cut frame by frame by frame.”

One challenge in editing was to make the Ford GT40 Mk II and the Ferrari 330 P3 sound like they were reaching 7000 RPMs or higher because the cars were never recorded at those top speeds. Also, the timing of the picture cuts had to work from a sound standpoint. For instance, the shot would cut to a tachometer peaking at 7000 RPMs, so the engine sound would have to hold the rev up to a point before they could create a gear change.

“Sometimes the [picture] edit would have to change for dramatic purposes, but sound-wise we might not have enough to sustain that sound,” says Giammarco, who’s earned Oscar nominations for sound mixing on Moneyball and 3:10 to Yuma. “So there was communication about how those scenes developed.”

Director: James Mangold. Movie Studios: 20th Century Fox. Re-Recording Mixers: David Giammarco, Paul Massey. Supervising Sound Editor: Don Sylvester . Sound Designer: Jay Wilkinson, David Giammarco . Foley: Anna McKenzie, supervisor, Dan O’Connell, artist, John Cucci, artist, Kevin Schultz, Foley mixer, Andy Malcolm, artist, Goro Koyama, artist, Richard Duarte, Foley mixer, Davi Aquino, Foley recordist, Don White, Foley mixer. Composer: Marco Beltrami, Buck Sanders. Music Editor: Ted Caplan. Production Mixer: Steven Morrow.

ORIGINAL SCORE

1917

There’s so much talk about director Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins’ continuous-shot approach to filming 1917, and rightfully so. That was a daring decision that required full commitment from cast and crew. But it paid off big time, delivering a feeling of immediacy like no other war film has.

In terms of score, composer Thomas Newman was presented with a unique challenge on 1917—to write music that supported each moment without ever reflecting on what just happened, nor leading the audience into what happens next.

“It became evident that the more music tried to interpret dramatic events, the less exciting they were likely to be,” says Newman. “If the music got ahead of itself, it ran the risk of making the landscapes less menacing and the action, in turn, less involving. This was often counter-intuitive, as film music typically reinforces action and character.”

His 1917 score mainly stays in lockstep with the action, but in rare instances it runs counterpoint to it. For instance, there’s a night scene in which Schofield (George MacKay) moves through the ruins of Écoust. There, the “music is allowed to step forward into a kind of dystopic wonderland—a cold and beautiful landscape despite the desperate circumstances. Ironically, the dream music I wrote is entirely orchestral, a rare example for me of an inverted psychology. I very much enjoyed that surprise,” shares Newman.

You’d think a score for a WWI film would be wholly orchestral, but Newman takes a different route, combining traditional orchestral instruments with more esoteric elements, like “carom ambiences, rubbed quartz bowls, flutes resonating more breath than tone, processed field cadences, struck and bowed dulcimers,” he reveals.

Director: Sam Mendes. Movie Studios: Universal Pictures. Re-Recording Mixers: Scott Milan, Mark Taylor. Supervising Sound Editor: Oliver Tarney. Sound Designer: Oliver Tarney, Michael Fentum. Sound Effects Designer: James Harrison. Foley: Hugo Adams, supervisor, Sue Harding, artist, Andrea King, artist, Adam Mendez, Foley mixer. Composer: Thomas Newman. Music Editor: Peter Clarke. Production Mixer: Stuart Wilson.

Harriet

Composer Terence Blanchard’s score on Harriet is both heavy and hopeful, capturing the rebellious courage and determination of Harriet Tubman (Cynthia Erivo).

Instrumentally, Blanchard chose to work with a full orchestra because “the breadth and scope of an orchestra allows a composer to create drama and intimacy and suspense,” he explains. Blanchard’s score uses broad harmonic passages with brass and low strings to enhance the drama. “I also used the genius of pianist Fabian Almazan’s creativity to create very unique piano tones, which gave birth to a unique sense of Harriet’s spirituality.”

That can be felt in the sparse piano notes that linger over beds of celli and violas in “Broken Contract,” “I’ll Be With You” and “Freeing Rachel.” Much of the score was recorded at Ocean Way Nashville.

Instead of orchestral percussion, Blanchard chose ethnic percussion. It drives the action on “We Go Left,” for example, reinforcing the peril of Harriet and those she rescued. Blanchard says, “I thought it best to use ethnic percussion to give us the sense of how her ancestors helped guide Harriet on her journey.”

The essence of Harriet’s score is best represented by the piano-and-strings-based track “Flash,” which plays as Harriet runs to board the ship after the death of Marie (Janelle Monáe). “The music for that scene and the scene itself portrays so many aspects of Harriet’s character—compassion for human life; a strong conviction for freedom; and her reflective spiritual nature.”

Blanchard earned his first Oscar nom last year, for his score on BlacKkKlansman.

Director: Kasi Lemmons. Movie Studios: Focus Features. Re-Recording Mixers: Skip Lievsay, Blake Leyh. Supervising Sound Editor: Blake Leyh. Supervising Foley Editor: Dave Flynch. Composer: Terence Blanchard. Music Editor: Marvin R. Morris, Jamieson Shaw. Production Mixer: William Britt.

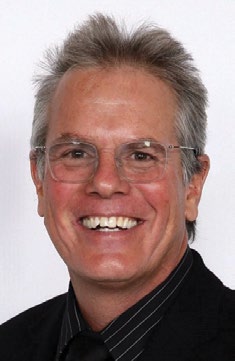

How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World

Composer John Powell captures the colorful adventure of How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World in an orchestral score featuring bold horns, big drums, and tinkling bell tree glisses and harp plucks that add a sense of wonder and joy.

Powell, who has worked on all three How to Train Your Dragon films, notes that much of the adventure comes from flying, and so he had to compose “flying music,” which is unique to his work on the Dragon movies. “I don’t know why, but it came very naturally to me. I must have listened to a lot of music in my life that always told me, somehow, I could fly,” he says. “You use your own backstory in these moments. The Dragon scores are all about finding tension and release, conveying a sense of flying, and having a tone that is joyful and fun.”

When Hiccup and Astrid first ride Stormfly into the hidden world of the dragons, director DeBlois asked Powell to do something extra special with the score. Powell turned to vocalist Jonsi (of Sigur Rós), who created layers and layers of vocals that float over Powell’s bed of music in “The Hidden World” track. He says: “It gave us the feeling of entering a new and spiritual place which we haven’t been to in any of these films. There is no instrument on Earth that could be as pure and spiritual, emotional and exotic, as the voice, especially Jonsi’s voice, which is really unusual and beautiful.”

Powell earned a 2011 Oscar nom for his score on the first How to Train Your Dragon.

Director: Dean DeBlois. Movie Studios: DreamWorks Animation/Universal Pictures. Re- Recording Mixers: Scott R. Lewis, Shawn Murphy, Gary A. Rizzo. Supervising Sound Editor: Leff Lefferts, Brian Chumney. Supervising Sound Designer: Randy Thom. Sound Designer: Al Nelson. Composer: John Powell. Music Editor: Jack Dolman. Production Mixer: Tigue Sheldon.

A Hidden Life

Composer James Newton Howard teamed up with director Terrence Malick for the first time on A Hidden Life. His score captures the emotional turmoil of Austrian farmer-turned-war-resister Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl), who refuses to fight for the Nazis during WWII.

The standout component of Howard’s score is the solo violin, played by internationally acclaimed Canadian violinist James Ehnes. His performance oozes sentiment like sap from a cut maple tree.

The score is reflective and meditative, with repetitive themes—like those heard in the title track “A Hidden Life,” “Hope” and “Knotted”—that epitomize the stalled existence of Jägerstätter and his family. The somber, brooding tone of “Morality in Darkness” and “Descent” conveys their trepidation as Franz endures months of imprisonment awaiting a trial that they know will ultimately conclude with a death sentence.

Howard has earned eight Oscar nominations thus far, most notably for his scores on The Village, Defiance (another film involving resistance against the Nazis) and The Fugitive. He’s composed more than 160 scores, including those on all four The Hunger Games, both Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them films plus the one slated for 2021, The Bourne Legacy, The Dark Knight, King Kong, Signs, Falling Down and the original 1990s Flatliners, to name just a few.

Director: Terrence Malick. Movie Studios: Fox Searchlight. Re-Recording Mixers: Brad Engleking, Stephen Urata. Supervising Sound Editor: Brad Engleking. Foley: Bastien Benkhelil, artist, Carlos Flood, Foley mixer. Composer: James Newton Howard. Music Supervisor: Lauren Mikus. Production Mixer: William Franck.