Jazz Gaudet, an assistant to veteran engineer Shelly Yakus at Aftermaster Audio Lab Studios, cues up “Trains,” a track produced by longtime colleague Jack Douglas for a new project, SILVERPLANES. The cueing is taking place on a 1/4-inch tape machine on which Yakus has just completed his mix, producing the familiar “whirring” all engineers who started in his and his producer’s era know and love. “Ahh, the sound of tape,” Douglas smiles.

The playback is also distinctly analog-sounding, which was the goal of Douglas and artist Aaron Smart. Smart is a fan not only of Douglas’ work—along with that of engineers Yakus, the late Geoff Emerick and Jay Messina, who would mix the album—but also of genuine analog equipment and the sound it produces. “Aaron is a real gear freak,” the producer says. “He’s totally into it.”

Smart was already close to the Douglas circle, having befriended the producer’s son, Blake, ten or so years ago. He was fronting Hayes, a band featuring drummer Jesse Kramer, son of Aerosmith’s Joey Kramer. “Jack came to see us once, but that was the extent of it,” the artist recalls.

Having become fascinated by the recording process, Smart acquired a studio (known as “Baby-O” at the time, which Smart renamed “Regime”) in the old Hollywood Athletic Club that was built in the 1970s and formerly owned by M.C. Hammer. The live room, which measures about 25 by 20 feet, with a high ceiling, is accompanied by a small but comfortable control room populated by a 24-channel Quad Eight Pacifica console and loads of analog gear, which Smart has taken to collecting.

There are also plenty of left-handed guitars—Smart being a left-handed player—which came in handy when Paul McCartney was working with producer Greg Kurstin at Henson. “He asked someone, ‘Do you know where I can get some really good left-handed guitars?’” Douglas remembers. “Aaron got the call.”

At some point, Douglas was looking for a small room to work in with a female artist he was producing, and his son suggested Smart’s place. Douglas booked it.

Related: A Discussion with Geoff Emerick, by Maureen Droney, Oct. 1, 2002

A few years ago, Smart had a new band and was ready to do some recording, telling his friend Blake, “‘I’m looking for a producer like Butch Vig, somebody who’s an idol of mine.’ Blake said, ‘Why don’t you send it to my dad?’” Smart recalls.

Says Douglas, “Blake told me, ‘You remember Aaron? He’s got a new band, and he’s looking for someone to produce him. I think you guys should get together.’”

The two met at Douglas’ house in L.A. and listened to the demos Smart had put together. Douglas, instantly intrigued, asked who it was, and where he’d done it. Smart said it was him. Douglas said, “We should have done this 10 years ago!”

“He told me what he was doing,” Douglas states, “that he wanted to do things as analog as possible—not just on tape, but with an analog desk and analog gear.”

Says Smart, “It feels to me like the golden age of recording was the late ’60s through the ’70s. When I started recording, it was to blackface ADATs, which were kind of crunchy and harsh, and eventually to Pro Tools. But I would occasionally record to tape. Whenever I’d record to those other digital media, you’d have to have some really nice chain in front of them to make them sound anything close to tape. But with tape, you can even have a lower-quality chain in front and it would sound better. If you listen to records Geoff, Shelly and Jay mixed, even when playing them on CD, they still resonate. Analog is rounder, the bass has no limits, and the highs don’t have a crunch limit. Everything’s smooth, and that’s what I’ve been striving for.”

Tracking with Jack

The two got together with Smart’s band at his studio (which Douglas had dubbed “L.A. Confidential,” also the name of a label he and Smart recently introduced) and tracked 15 songs, which were then mixed by engineer Warren Huart, one track of which, “Falling Asleep,” was released as a single in summer 2017. Mixed at Huart’s L.A. studio, and using some of Douglas’ own analog gear, the mixes featured “a very contemporary style of mixing,” the producer notes.

Related: Classic Tracks: Aerosmith “Walk This Way,” by Robyn Flans, March 21, 2017

Even before those tracks were released, Smart and Douglas began taking the next step. “We said, ‘Let’s record some more tunes, but let’s look at it a little differently,’” Douglas recalls. “‘Let’s go for a really big, open sound. And let’s think about different guys to mix it, who would think about it in a more spacious, open way.’ I said, ‘I know just the three guys who would be perfect for this.’”

The songs were again recorded at L.A. Confidential, Douglas engineering the recordings, assisted by Ari Judah, and tracking to Pro Tools. The project was spread over a long time period, allowing the producer to work other projects, including Joe Perry’s recent solo album and film projects.

Douglas’ process typically begins with the recording of an acoustic guitar and drums, the former strictly for reference for tracking a vocal later, giving the song its base feel. He then wipes the acoustic and begins working on the basic rhythms.

“I get a really good reference vocal down so I can build around it.” The idea, he notes, is to approach the recordings as he was taught by his mentor, Roy Cicala: “Try to capture the sound you want while recording it, with reverb, compression, or whatever it needs. I try to give Shelly and the others the biggest, fullest sound I can give them, as many elements as they need.”

Smart himself would play all of the songs’ rhythm guitar tracks, also adding some melody and arpeggio parts. For lead, Douglas used several different players, including Seattle guitarist Sean Woolsten-Hulme. “He’s the kind of guitar player who probably doesn’t even know how to play a scale. But he has all these pedals—I tell him, ‘Just play what you feel. Don’t worry about the chords. Just listen and play over the top of it, and just go crazy.” Later, Douglas would build comps from five or six passes with the musician.

Veteran session player Randy Mitchell would show up and, as Smart explains, “Jack or I would hum him a part, and he would play it for me a second later, exactly how I was singing it, and then make it better.” Jason Johnson, formerly with Pete Yorn, also played on several tracks. Bass was tracked by Billy Mohler, a member of Smart’s band.

Smart’s lead vocals were typically recorded with a U47 or M49, with an Altec 633A “salt shaker” even put to use on one track. Douglas would record with compression on occasion, depending on if he was going for a particular effect. Background vocals were sung by a pair of Australian brothers, The Kin. “They’re my secret weapon,” Douglas says. “I’ll sometimes use a ribbon mic on BVs, just so they stand in a different place.”

Douglas took full advantage of Smart’s gear collection—and his own. “There are racks old Neve mic pre’s,” he says, as well as Spectra Sonics M-502 PRO and Telefunkens. “One of them alone, a mono Telefunken, is worth like $15,000!” Douglas laughs. “We’re careful with that one.”

He had lots of great mics to choose from as well, including Neumann U47s (short and long), a FET 47, which Douglas would use on the outside of Smart’s kick drum, a rare stereo 67 (SM69, featuring two capsules that swivel), U48s and M49s, old RCA ribbons mics, and Neumann Telefunken M49s.

In addition to the FET47 on the kick, U67s on overheads and U87s on the toms, Douglas miked Smart’s snare drum with four mics, thinking ahead so he could provide options for his three mixers, who might want to exercise different approaches using different combinations.

One, a favorite, is Douglas’ rare classic Altec 633A “salt shaker,” whose sound Smart found so appealing that he bought one himself on eBay, both pieces getting put to work on the recordings. On the snare, it is accompanied by an RCA BK5 omni ribbon mic, which, Douglas notes, “was created for Warner Bros. when they needed something to record gunshots. It can take that kind of sound pressure level. And it’s warm.” It was also sometimes the only mic his and Yakus’ mentor, Roy Cicala, would use, Douglas notes. A Shure 57 and a Telefunken rounded out the set.

Related: Geoff Emerick Shares His Beatles Memories, by Matt Hurwitz, Aug. 1, 2006

The four are kept in phase, he notes, “which Pro Tools is great for because you can align the phase of anything you put into it.”

Another trick: Douglas would place the stereo Neumann SM69 in the studio’s bathroom shower. “I open the doors to the bathroom, and even though it’s a good distance from the drums, it gives me a nice, natural reverb.”

The producer would also sometimes place an Altec mic mixer between the mic and mic pre to add another kind of color. “It kind of lo-fi’s it, in a way. But it adds a distinctive personality.”

Once tracking on the 15 songs was completed, Douglas decided which five would be mixed by whom—Messina, Yakus or Emerick. All would mix through an analog desk, using as much analog outboard gear as possible. “With the younger school of mixing,” says Emerick, “they’re looking at a screen. They’re not hearing it. You need to be painting with tonalities, thinking of the sounds and instruments as colors.”

“I chose which songs for which mixer by how I felt they would relate to the tracks,” Douglas explains. “Jay and I have a lot of history; we did all of those Aerosmith records together. I’m just super comfortable. I don’t have to say very much, and he totally gets it.”

Douglas and Smart especially wanted to take advantage of Messina’s ability to create a strong sense of depth, assigning him the tracks that were more spatial. “He’s the king of space,” notes Smart. “When you listen to his mixes, it’s as if you’re sitting 10 feet back from the band and just looking at it. And it feels as if the drums are two feet in front of you. His are really dimensional.” Adds Douglas, “His are like you’re watching a movie unfold.”

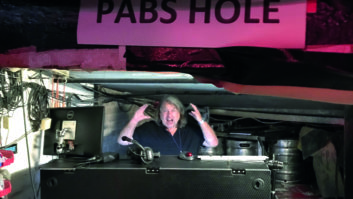

Mix Master: Shelly Yakus

For Yakus, he notes, “I would listen and think, ‘Does this have a Tom Petty or a U2 feel?’ With Shelly, it sounds like there’s a rock band in the room.”

Emerick’s tracks, he says, “are anything in there that resembles The Beatles,” the mixes having the engineer’s distinctive Apple sound. Notes Smart, “They’re totally different—they’re English. The toms are way up and the highs are sparkling, just floating around.”

Both Messina and Yakus were able to take advantage of a rack of gear Douglas takes wherever it’s needed. “There are Pultecs, 1176s, Pye compressors—which are very rare and difficult to find; I found four of them—Fairchilds, a Neve compressor and Neve line amps,” he says proudly. “There are four Neve EQs, from the ’50s and ’60s, which are on a lot of great records.”

Notes Yakus, “So many young guys I’ve encountered think ‘newer is always better,’ and it’s not. They used transformers in a lot of the older equipment, which isn’t used much now. The transformerless stuff tends to sound thinner, brighter; it’s devoid of that organic feel. Transformers help you capture the band.”

Also available was a vintage 2-channel Fairchild 670 tube compressor/limiter, likely from the late ’50s or early ’60s, which Douglas acquired from producer David Kahne during his time working with Messina on the songs in July 2017.

“It’s an incredible piece of gear,” Yakus notes. “It gives you not only a warmth, but a depth, front to back. It’s like when you’re standing in a club, there’s a depth there. This helps you retain that, and you need it, because when the mix is flat, everything in the mix is fighting for the same space. So you need to have some depth. People call it ‘layers’ sometimes, but it’s depth. Some instruments are further back, yet you can hear them clearly through the other instruments. The Fairchild allows you to do that.”

Such equipment only bolsters the SSL SL-4000 G+ mixing console at Aftermaster Audio Labs studio. Yakus and Douglas have a long history dating back to Yakus’ arrival at The Record Plant in New York in 1970, following his tutelage under Roy Cicala and Phil Ramone at A&R.

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get it delivered right to your inbox.

“I came in as a janitor there in 1969—literally—and worked my way up to being Shelly’s assistant,” Douglas says. “Both Shelly and Jay came from A&R before going to Record Plant. We were all working in the same rooms, with the same equipment. So we had a pretty good idea of what we were gonna do.”

Notes Yakus, “I just listen and try to bring out what Jack was reaching for, without discussing it. I can hear it.”

Yakus starts building his mixes “from the voice down instead of the from the bass up. If I get a voice sound that works for me and Jack, then the other instruments have a guide, to get the other instruments to support that voice instead of fighting the rhythm of his voice. It’s the framework for everything in the song. If you get those to sound good, then it helps me to get everything else sound better. If I put the vocal in last, I’m forced to change the sound of his voice to fit.

“I’m trying to get the voice to have as much personality as possible, so that it evokes an image from the listener,” he adds. “No one really knows what the artist looks like, unless you’re a top artist. Even if it invokes an image that isn’t the person, you’ve got them thinking about it.”

He will sometimes use small amounts of limiting (Tube Tech Limiter, a Pultec or Bricasti reverb), and even a little bit of digital delay from an AMS unit “to enhance his movement, with his words and expression. Don’t forget, he’s competing with the band. If it goes to the chorus, you can’t suddenly lose the singer because he’s drowned in effects. We’re really emotion salesmen, so to speak. You want the feel to take over. Those things are just there to enhance the strength of the feeling that’s already there.”

Mix Master: Jay Messina

Messina takes the opposite approach, instead starting with developing the drum sound and adding the vocal last. “I’ll start with the drums, then add the bass to get the foundation of the rhythm section, and then sneak the guitars in,” he explains.

The engineer used all of the mic options Douglas provided for the snare, and, on occasion, would take a sample of a drum track, “just to toughen up the snare, when I felt I needed it,” sent by Douglas from the multitracks, to Messina at Avatar in New York. The room features the same desk Yakus was using, an SSL G+.

While his rack remained in L.A., Douglas would bring along a favorite goody, as did Messina. “Jay brought in his Korg Kaoss Pad [sampler and effects processor], and I brought in a piece of gear nobody has, called a Ramsa Phantom Speaker Synthesizer,” Douglas says. “If you’re sitting in the middle of your speakers, you’ll hear an instrument sound as if it’s going from the left speaker to behind your head and circle around. It’s incredible.”

To achieve the depth Douglas wanted, seeking to avoid “anything overcompressed and flattened out, where the snare’s in your face, the vocal’s in your face, and the bass drum and guitars are in your face,” the producer notes, he turned to Messina and his ability to mix spatially. Though the engineer notes that it all starts in Douglas’ recording. “Jack will commit to having some processing on tracks during recording, which I like—that’s part of how you get some of that depth. If the guitar track has some processing already, with delays, it gives it its own special place to appear in the picture.”

“I’ll use a particular echo and have the repeats work in time with the track,” Douglas notes. “Then I hand it off to Jay, and he’ll add his EQ to the whole picture. Then it comes to life. It’s a lot like turning a picture over to the editor. The cameraman has done his best, then it’s up to the film editor to put it together in the proper way.”

Messina agrees: “You can liken the sounds to different colors. And sometimes those colors are just perfect the way they are, others maybe you change the tint and maybe a little EQ. You manipulate them to make them create this one image, as they sit together.”

Mix Master: Geoff Emerick

Emerick, assisted by Spencer Guerra, mixed his five tracks at North Hollywood’s LAFX Recording Studio, a facility he’d been using since tracking Nellie McKay’s My Weekly Reader in 2015, on recommendation of friend/colleague Bill Smith. Its main attraction to the veteran engineer was the studio’s vintage API 2416 custom 40-input, 48-return, 16-bus console, with 550a EQs custom built by Brent Averill and modified by Steve Firlotte.

“I fell in love with API boards when I was doing the America albums at Record Plant,” Emerick states. “It has this beautiful depth on the bass and a clean high end the Neve consoles sort of had, but was hard to get. And Spencer and I have been working here now for so long that, once I heard the tracks from Jack, I knew what we could get here.”

As was the case with all three engineers, the mix was made to 1/4-inch tape, something the younger Guerra has become quite adept at using, for everything from printing mixes to tape slap and multitrack recording. “We did it at 30 ips,” Emerick says, “because it’s got a slightly higher end on the top, more hi-fi, whereas I’d use 15 ips for Elvis Costello, where you get this extra depth on the bottom. It’s something Pro Tools can’t reproduce.”

Emerick and Guerra would use a combination of both classic analog tools and a few favorite digital ones to, as he puts it, “paint with sound.” “Geoff’s directing an orchestra here,” as Douglas puts it.

Though Emerick built the mixes starting with the drum track, he was keen to study Smart’s vocals, which were central to all of his mixes. “The first thing I noticed when I lifted the tracks up was that the drums don’t sit like a drum kit, even before the vocal came in. Jack told me, ‘You know, he sings.’ He doesn’t sing a guide vocal, but because he wrote the songs, he’s singing them while he’s playing and working his part around them. You can feel it in the drum pattern. It flows. It’s got light and shade, it flows along the lyric.” The vocal, to Emerick, is not simply a singer, “It’s an instrument within the track, and the drums flow with the vocal.”

The first user of tape-based automatic double-tracking (ADT) on a Beatles record, Emerick had Guerra figure out a way to reproduce the effect using both mechanical and digital equipment. “It’s a combination of both worlds,” Guerra states, though Emerick refused to allow him to give away the secret!

The duo would introduce carefully timed delays to the guitars, in concert with plate reverb, to give them a unique sound. “We have an EMT plate here,” says Guerra, “and we’d give it a large pre-delay through the Lexicon PCM 42 delay processor, depending on the timing of the song, like 120 to 170 milliseconds, before going to the plate reverb. So there’s a long pre-delay and then a heavy tail on the reverb.”

In addition, a Little Labs Voice of God 500 series bass resonance subharmonic synthesizer plug-in from UAD helped “for low-end detail,” he notes. Also, a vintage “square-faced” Neve 2254 (and 33609J) compressor, a favorite of Emerick’s helped shape the guitars.

Related: Classic Tracks: John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s “Watching the Wheels,” by Matt Hurwitz, Dec. 8, 2010

For the drums, Emerick and Guerra would apply a vintage dbx 160a compressor/limiter, on the kick and snare. But Guerra has also gotten a thorough education via his mentor’s use of the UA 1176. “Geoff’s definitely opened my eyes to the versatility of the 1176,” he states. “I’ve always loved compressors, but this man can make that compressor work on almost any instrument. He has a really interesting way of setting them. He’s not afraid to heavily compress if he needs to, or he’ll go light if that’s what the sound’s calling for.”

Emerick would indeed use the 1176 for stereo bus compression—actually a pair of them rather than a stereo unit. “That’s something I cannot wrap my head around at all,” Douglas confesses. “I’ve listened to that on headphones, and there’s no center shift.” Explains Emerick, “The stereo pair shares a power supply, which means the power into the attack is not there. The Fairchild 660s have their own power supply. That’s why the stereo pair doesn’t sound like a 660.”

The tracks were mastered by Ryan Smith at Sterling Sound in New York, and released on Smart and Douglas’ Mohler’s Volume Unit Records, an imprint of their Make Records label (itself owned by Smart and Mohler). The songs were issued as three downloadable EPs—one for each mixer, with an additional four tracks remixed by Yakus at LAFX, to be issued as B-sides—available for download and likely a vinyl LP set.

Smart and Douglas have also been busy building a new studio, dubbed Make Records Studio, near downtown L.A., designed by George Augspurger, to continue the legacy of analog. “We’re trying to set the bar higher,” Douglas states, “to avoid working with just a mouse, because it’s gonna sound like a mouse. We would prefer you sound like an elephant.” His mentor, Roy Cicala, would indeed approve. “He would come in and say, ‘It sounds like a record.’ What more can you ask for?”