Nearly every month, while discussing a certain problem or issue, a technical concern pops up that I don’t feel comfortable about glossing over. Often, this detour ends up being the column’s focus rather than a footnote.

Audio interconnectedness between myself and my readers is this month’s topic. I only wish that my column fully realized the potential of its title. This isn’t quite the audio version of the play that begat a movie before becoming a party game (centered on Kevin Bacon). However, just as I would finish up a column and it went to print, I received numerous e-mails from my readers questioning and probing for more about the column that they just read. So here is my printed “blog” — from turntable optimization to MP3 compression.

THE TURNTABLE CONNECTION

Cave dweller that I am, it’s rewarding to get feedback from other cave dwellers. Of two seemingly unrelated recent columns — “Not a Mic Preamp Shootout” (January 2006) and “Gettin’ Into the Grooves” (March 2006) — one got me out of the country and both turned me on to a new circle of friends and experts. Of course, it’s always best to start at the beginning.

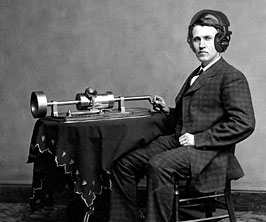

Our industry has always moved quickly to embrace new technology, with all of its faults, for the benefits and new sounds it has to offer. Had Edison or Berliner given up after those first attempts, we might not be where we are today.

In the earliest days of recorded sound, the primary obstacle — between the original performance and its reproduction — was the material from which records were made. Shellac was smooth-ish on the surface, but crude playback equipment (acoustic phonographs and the early crystal cartridges of the electrical era) quickly wore into the porous underlayer, the equivalent of sandpaper compared to vinyl. Needle pressure in those days was a fraction of a pound!

Note: Edison’s cylinder was the Betamax of its day. The playback mechanism design minimized wear to the cylinder. Edison’s team was constantly experimenting with materials, starting with a tan wax (easy to record), then an improved black wax and ending with “Blue Amberol” — a plastic similar to celluloid. The recordings are remarkable for their time. The library of the University of California, Santa Barbara, is posting its collection at www.cylinders.library.ucsb.edu — listen for yourself!

Everything changed in the late ’40s. Analog tape, the “45” and the long-playing 33⅛ rpm LP ushered in the era of high fidelity, aided by vinyl’s superior signal-to-noise ratio, microgroove technology and lightweight pickups. Ten years later, stereo added dimension and depth, but on record, it also exaggerated a low-frequency mechanical idiosyncrasy. At the other end of the spectrum, another noise problem developed as more tracks were squeezed onto analog tape.

A mono groove only has lateral (back and forth) motion, and that stereo information also adds vertical (up and down) modulation. Turntable mechanics combined with disc rumble (from the replication process) can also vertically modulate the disc surface. This is ignored by mono pickups (or when listening in mono) but is fairly obvious in stereo, especially on quiet material. Cartridges with poor vertical compliance would either do damage to, or be bounced out of, a stereo groove.

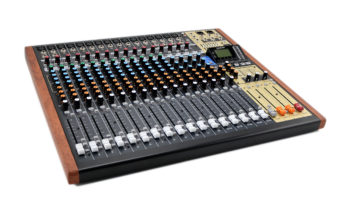

The mechanical aspects of recording technology are not only the most tangible, but they are also the most easily remedied. For example, as seen in “Gettin’ Into the Grooves,” the type of mat under the record combined with a weight placed on top (over the label) can dampen disc resonance. Microphones are another example of how the electro-mechanical process works (and doesn’t). Likewise, in “Not a Mic Preamp Shootout,” a shock-mount is the most obvious solution and well worth the investment. Non-resonant designs and materials are worth paying extra for, but it’s not rocket science: Just about anyone can tweak a little resonance out of a mic body, mic stand or turntable base.

ARE YOU EXPERIENCED?

Long before I ever stepped foot in a studio, I listened as close as was possible to records — crudely peering into the grooves with a magnifying glass and rabidly tearing apart quite a few tape recorders. I wanted to make my stuff work better.

I remember the first time I heard a 2-track safety copy of The Beatles’ Abbey Road in Bearsville’s B control room. During my formative years, I had played that record many times on many speakers. But to then listen on a full-range system without the scratches, mistracking, turntable rumble, wow or cassette tape flutter made it seem as if I had time-traveled to Abbey Road studios and stumbled into a session in progress. Now, everyone has access to the same playback quality we have in the control room. So maybe we should take advantage of it?

THE RAW AND THE COOKED

That early desire to get closer to the performance was, at the time, all I had. My turntable maintenance piece borrowed heavily from those early experiences. It also attracted the attention of Michael Fremer, the senior contributing editor for Stereophile, editor of musicangle.com and a hardcore vinyl enthusiast. It’s one thing to be able to play records “just for fun,” but if the grooves are treated as if they are the only master, the quest is on to minimize, if not subtract, as many of the idiosyncrasies as possible.

There aren’t many people who are seriously knowledgeable about analog data-retrieval devices (record players). Fremer has made a profession out of getting the most from the grooves: whether he’s tweaking the mechanics and auditioning cartridges or minimizing jitter and auditioning converters. The next step is finding “good” recordings — you know, the handful that everyone plays at tradeshows to show off their gear.

LES BITS

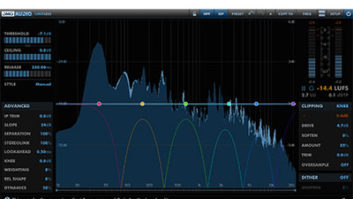

Many a professional career in this industry started with tinkering; some tinkerers became after-market specialists, while others became manufacturers outright. Bob Katz falls into more categories than that; he is, after all, the master of his digital domain. I ran into him in Montreal. We were both there at the request of The Association for Professionals In Audio (www.aspraudio.org) — me to expand upon and provide sonic examples of my “Not a Mic Preamp Shootout” column.

Katz’s presentation centered on the obvious benefits of relaxing mastering levels. He suggested that our industry adopt a calibrated monitoring approach similar to that used by film mixing engineers. By establishing a reference level to which monitoring and metering are calibrated (and to which reference recordings can be fairly assessed), it will be easier to prove to a customer that louder is not better. For a CD honor roll that lists examples above and below a handful of reference discs, visit www.digido.com.

Adopting a common language would improve communication and awareness among both professionals and our clients. For example, we should use the term “coding” to describe all data reduction (MP3, m4a, etc.) and reserve the term “compression” strictly for dynamics processing.

The examples Katz provided were spot-on and remarkably diverse, ranging from Black Sabbath to Marc Anthony, rap to salsa. He also did a simple subtraction — CD minus its coded offspring — to show just how frightening some MP3s can be when the source for the MP3 has been aggressively processed. I have a feeling that there will be a whole new type of hearing loss when the iPod generation rides that soft-knee into mid-life so that it qualifies for AARP membership.

SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE

We had volume wars in the ’60s, just like now. A.T. Michael MacDonald (not the singer, but the recording and mastering engineer at www.algorhythms1.com) recently asked whether jukeboxes had automatic gain control (AGC) to even out the discrepancies between disc levels. Indeed they did. But that didn’t stop Epic Records from making some of the most awfully loud 45 rpm records, one of the most egregious offenders being Lulu’s “To Sir With Love,” with the Dave Clark Five’s “Catch Us If You Can” also in that clubhouse.

Albums had much more conservative levels and were always pressed on vinyl. But 45s were pressed on both vinyl (soft and flexible) and polystyrene (hard and brittle). These days, excessive dynamics processing makes the worst MP3s. Back then, employing distortion to make louder records backfired when that record was pressed on polystyrene and played with a non-compliant (stiff) cartridge. The resulting additional distortion — of a stylus unable to negotiate the obstacle course — became permanent.

My point to this historical potpourri is simply to point out that poorly maintained, cheap consumer playback equipment — turntables, albums and bad cassettes — were the major obstacles in the reproduction equation. With those variables gone, we really should be taking advantage of current sound system capabilities.

Eddie would like to especially thank Chantal and Francois of

www.aspraudio.org

for hooking him up with Bob Katz.