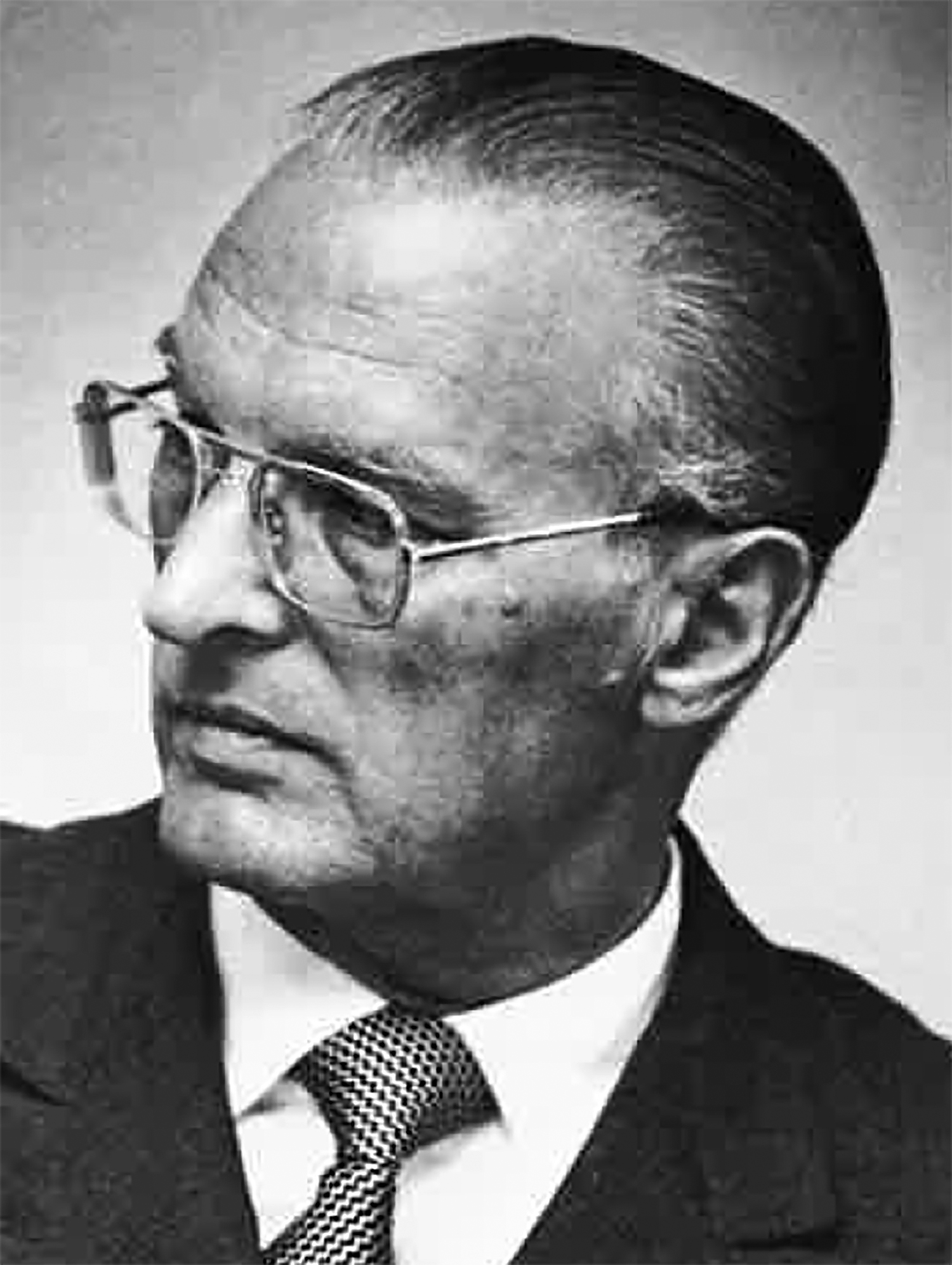

Studer’s story is a testament to time and technology. From its beginnings as a tape recorder manufacturer, the company built a reputation in consoles, and in the 1990s pivoted to digital technology. But back in 1931, Willi Studer was a Swiss teenager with an aptitude for engineering, an entrepreneurial spirit and some big ideas.

After graduating high school, Studer enrolled in an apprenticeship program, then abandoned it soon after to market his own radio receiver. He went on to design audio test equipment, including high-tension oscilloscopes, launching the Studer business in the basement of an old post office building near Zurich, with a staff of three. The company’s focus shifted to tape recorders in 1948 when Studer was contracted to convert 500 American-made products to European specifications. He quickly realized that he could produce a better machine, and two years later he launched the Dynavox T-26.

In 1951, the Studer company split into two brands. Studer recorders, initially marketed under the Dynavox name, found instant acceptance in professional circles, while the Revox line offered the same core circuitry but added consumer-friendly features such as IR remote control. (One of Revox’s most successful products, the A77 recorder, was introduced in 1967 and went on to sell more than 400,000 units.)

In 1952 Studer launched its first professional studio tape recorder, the A27, which was the first Studer machine to feature a three-motor drive design. The A37 followed, then the B37, and later the half-inch, 2-track C37 and its 1-inch, 4-track version, the J37, both of which went on to become recording studio standards.

Studer’s studio legacy was cemented when, in 1965, Abbey Road Studios purchased four J37 machines. At that time the Beatles were entering a deeply experimental period in the studio, layering and editing sounds to create groundbreaking new textures. The J37 is probably best known for its role in the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band sessions, when producer George Martin, engineer Geoff Emerick and the band spent four months recording, editing, track bouncing and mixing with two J37s manually synched in Abbey Road Studio Two. Soon the J37 would be found in nearly all of England’s major studios.

“Studer played a huge role in the rise of recording studios in Great Britain in the ’60s and ’70s,” says Howard Massey, author of The Great British Recording Studios. “From the J37 4-tracks in extensive use at Abbey Road in the mid-’60s—which enabled the development of ADT [Automatic Double Tracking], among other innovations—to the ubiquitous A80 multitracks in all their many configurations found in almost every English and American recording studio in the 1970s and 1980s, Studer represented the zenith of European craftsmanship when it came to tape machines.”

Studer recorders soon made it to the States. Recording and mastering engineer Bob Olhsson, who spent much of the 1960s at Motown Records’ Hitsville U.S.A., recalls that the facility owned four of the first C37 machines in the country, and they played a major role in the recording methods pioneered at the studio.

“The Studer C37s sounded incredible,” Olhsson says. “And their extended, very flat low-frequency response allowed us to accomplish extremely precise half-speed lacquer mastering at unprecedented cutting levels for the amount of low-frequency information present.”

Studer continued to develop tape recorders for the next quarter-century. In 1970, the company released the A80 professional studio tape recorder, which was based on a new modular design concept. It was followed by the A800, the first microprocessor-controlled recorder, in 1978, then the A820 in 1985. Studer’s first digital machines, the D820 and D820X, were released in 1989; the D827 DASH recorder followed in 1993.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, Studer was sharpening its focus on digital technology, forming Studer Editech after buying Integrated Media Systems, maker of the Dyaxis hard disk recording system. Other early Studer digital products included the SFC16 sampling frequency converter, DAD-16 disc cutting digital preview delay, the A725 CD player and the TLS4000 synchronizer.

In 1990 Willi Studer, set to retire, sold the company to the Swiss Motor Columbus Group, and in 1994, Studer was acquired by Harman. (The Revox group was sold to private investors.)

Following the sale, Studer began focusing more heavily on developments in digital mixing console technology. Throughout its history, Studer had been a leader in console development, starting with the Model 69 portable tube console in 1958, the 089 fully discrete 12×2 console in 1968, and the 289, thought to be the largest console at the time, in 1972.

By 1993, Studer had launched its first large-scale digital mixing console, the D940. In 1995 the Swiss National Broadcasting Company’s first all-digital broadcast system, based on the Studer D941 console and Studer MADI router, went on air.

Studer continued to develop both analog and digital desks for broadcast and live production, including the 928 analog console, the OnAir Series of digital broadcast consoles that pioneered the Touch ’n’ Action user interface, and the Vista Series, which features Vistonics “knobs in glass” technology.

Seventy years is a couple of lifetimes in the professional audio and entertainment technology industries. With its current focus on broadcast and live sound technologies, including networked audio and core processing, Studer seems well positioned for many decades to come.

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get it delivered right to your inbox.