Bob Suffolk’s first day as a teaboy at Pye Studios in London might easily have been his last. It was 1966 and the Kinks were at their label’s studio working on the Shel Talmy-produced album Something Else by the Kinks, which included the hit singles “Waterloo Sunset” and “Death of a Clown.” When Suffolk pushed open the door with his first tray of teas, everyone in the control room looked up.

“I was in the tracking room—and Ray Davies was tracking a harpsichord,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘What have I done?’”

Not that Suffolk, then 19, was at all phased by being in the same room as a rock star. “I wanted to be in a professional band all my life,” says Suffolk, a keyboardist who grew up in the southeast London neighborhood of Beckenham, an area that spawned numerous musicians. His first band, a mod outfit named The Depth, rehearsed at a local school with Steve Marriott and The Moments, the band he left in 1965 to form the Small Faces. Marriott went on to found Humble Pie with local guitarist Peter Frampton and Suffolk later worked with younger brother Clive Frampton. Suffolk adds, “I was with David Bowie in the Beckenham Arts Lab,” a late-’60s creative arts scene that attracted local musicians such as Brian Auger, Julie Driscoll and Arthur Brown.

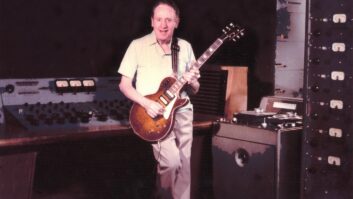

Suffolk’s ambitions never led to stardom, but his early years working as a tape op, apprentice mixdown engineer and recording artist provided a foundation for his studio design career of the past 34 years. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Before working at Pye, Suffolk had bombed around London on his scooter delivering sheet music for various publishers on Denmark Street, the city’s equivalent of Tin Pan Alley. A friend got him the Pye gig, and he also worked as a teaboy and tape op at other studios around town. Eventually he landed at Spot Productions’ studio in Mayfair.

“Spot Productions, which became Mayfair Sound, was a filthy hole at the time,” Suffolk laughs. “I helped out on sessions with people like Marc Bolan, the infamous Gary Glitter, who was then called Paul Raven, and Mike Leander.”

As 1975 rolled around Suffolk put together the Fabulous Poodles, a five-piece proto-new wave band combining elements of the Who and the Kinks with a keen sense of humor. Suffolk left in 1981, contributing piano to just a couple of tracks on the debut album. In the following years he formed the short-lived band Luxury with Squeeze bass player John Bentley, and he collaborated with musicians from Kate Bush’s band and others. But a new career beckoned.

“A friend of mine bought an abandoned rehearsal complex and asked me to help design and put it together,” he says. “My very first room designs were for Prime Time rehearsal studios, near London Bridge. After that I kept getting asked to design studios, but I didn’t really think of it as a job until I designed the control room at Elephant Recording Studios. The manager of Trident Studios was in there. She loved the vocal room that I had designed and built, a Tom Hidley-influenced room—dead ceiling, live floor.” She invited Suffolk to pitch his ideas for a Trident remodel.

Understandably nervous, Suffolk met with renowned engineer Barry Ainsworth at Trident. “He said, ‘Why should I pick you and not Tom Hidley to do this room?’ I said, ‘I’m younger, I think I’m better’—which was a lie—‘and I think I’m cheaper.’ He said, ‘I’m going to let you do it. But if you eff it up, you know you’re ruined.’”

Suffolk was mindful of Trident’s legacy, having stood outside hoping to see The Beatles when he was 15. “The day I got a key to get in there and work was a personal thrill,” he says. One day, while Suffolk was playing Trident’s legendary piano—the one you’ve heard on “Hey Jude,” “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” “Killer Queen”—Ainsworth asked him what he planned to change in the main tracking room. “I said, absolutely nothing, the acoustics are perfect. I redesigned the control room, didn’t make a cent and Mr. Ainsworth loved my respectful design style, which left the famous sound untouched.”

By the end of the project Suffolk had refurbished both Studio 1 and 2 control rooms and all the vocal rooms. In Studio 2’s tracking room he did something unheard of at the time: “I found a window behind a wall, opened it up and brought light in.”

He continued to work on London facilities such as Copy Masters and Animal House, a studio with a resident toucan. “There was no school of audio or acoustic design then,” says Suffolk. Instead, he learned through experience, study, working with numerous talented engineers, and speaking with Glyn Johns and other producers.

Plus, he says, his childhood had set him up for a life in music and sound. “My mom was a musician, and my father was an architect and an inventor for the Royal Air Force in the last war. He had an electronics shop and taught me about harmonics and frequencies. I was always playing with oscillators when I was a kid.”

But change was in the air again. Suffolk had visited the U.S. and liked what he saw, eventually relocating to Texas. The rooms that Suffolk encountered when he first visited the States typically had live ceilings and dead floors. “Tom Hidley was a genius; he turned rooms upside down. And it worked,” he says.

The rooms in which Suffolk had initially worked during his early years in London were relatively dead acoustically. “Until I went into some of Hidley’s rooms—his rooms were fantastic, so I studied some of his studios and plans. Tom Hidley has been a great influence in my life as I have worked both sides of the glass in many of his studios,” he says.

“In fact, there are many great designers I admire,” he continues, “but at Suffolk Studio Design we do custom design for the client’s taste and style, but always with correct acoustics to fit the style the client wants—modern, contemporary, vintage. I won’t do cookie-cutter rooms.”

Suffolk prefers 12-plus feet of ceiling height to accommodate HVAC, silencers, acoustic treatments and so on. “And I like the tracking room ceiling to be 14 or 15 feet,” he explains. “The higher the better, as long as the room also has the width and the length.”

Niles City Sound in Fort Worth, Texas, for instance, has an 18-foot ceiling. The raised control room sits on a 4×4-inch sand-filled steel framework with the window looking down into the tracking space, a design borrowed from Pye’s Studio A, he says, with a staircase inspired by Abbey Road. “I installed a 110-year-old wood floor in classic herringbone style,” he adds.

The facility is among his favorites, along with Pleasantry Lane in Dallas and Paul Middleton’s Palmyra Studios in Palmer, Texas. But if he had to pick one favorite, it would be Memphis Magnetic Recording, a facility in which Suffolk recently partnered with co-owner Scott McEwen, an engineer and producer, and his wife Claire.

“I’ve done everything I’ve always wanted to do in a studio there,” he says. “Very musician-friendly, down to the lighting and comfort. There’s a tracking room big enough for an orchestra, and a large vocal and control room.” Artist accommodation and a second studio are in the works.

“We put in a panoramic window. There’s a lot of engineering in our 18-foot panoramic window; you have to get a structural engineer involved,” says Suffolk. “It’s the focal point of the room. Everyone enjoys the view of the entire tracking arena.”

At Memphis Magnetic, as with any studio he has built, Suffolk says, “I adjusted the acoustics to the room as we completed it. I’ve always used my ears and senses I have acquired. I like to be a part of the room and feel the acoustics within the room. I use test tones, naturally, but I do like to put on Donald Fagen’s Nightfly, no EQ. If I can hear the Fender Rhodes in stereo, zero phasing, and hear that bass and kick coming down and hitting me in the chest, I know the room’s pure. I tell younger engineers and designers, ‘If you don’t understand harmonics, displacement of sound reflections and the mix focal point, then you’re going to screw mixes up.’”

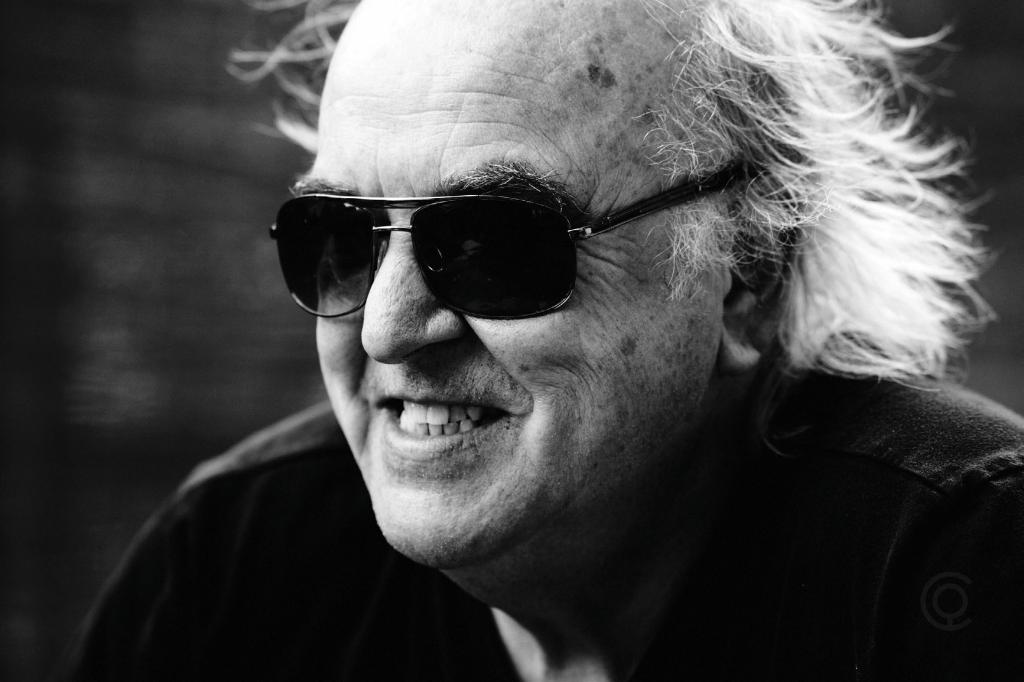

Now in his 54th year in the industry, with more than three decades as a studio designer, Suffolk shows no sign of slowing down. “I wanted to be a rock star, but I was getting tired of the music business,” he says. “But I feel closer to music now by having recordings coming out of my studios. I found I had a knack from an early age for sound, and I haven’t stopped. I’m on my 205th room now. That’s a lot of rooms!”