In early 1979, Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead was camped out at Different Fur Recording in San Francisco, working with director Francis Ford Coppola and studio owner/synth pioneer Patrick Gleeson on the Deleung Bridge cue for Apocalypse Now. Hart was playing The Beam, a legendary 8-foot, 13-string, guitar-like sound generator that could reproduce low frequencies and loudness like nothing else on the planet. But there was an audible buzz in the pickup.

In January 2019, Sound Research, working as an audio partner with HP, received a CES Innovator Award for the technology behind its OMEN HDR, a “you have to hear it to believe it” eight-transducer, consumer soundbar optimized for gamers, built for music and introduced as a package with HP’s new Emperium X OMEN 65-inch, 4k display.

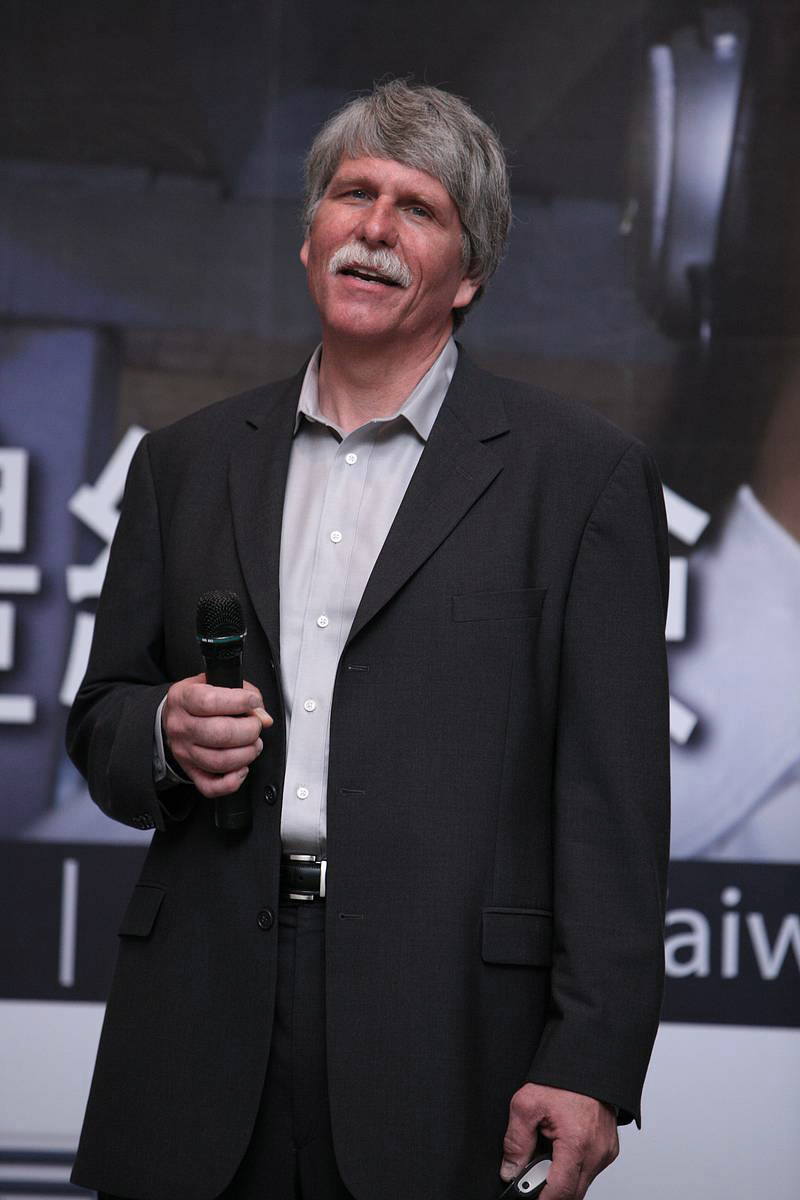

The connection between the two is Tom Paddock, founder of Sound Research. As a young engineer fresh out of San Jose State, he employed DSP and resynthesis—primitive and low-bitrate at the time—in developing a pickup that went down to 14 Hz and matched The Beam to the capabilities of the Dead’s Meyer Sound system, both in-studio and onstage.

Forty years later, he employed DSP, matched to current materials science and transducer technologies, in creating wide dynamic range, 105 dB stereo playback with minimum distortion and vibration, to make audio sound better at home, whether for games, movies or music.

In between Paddock designed and built studios, with an emphasis on artist’s personal spaces long before there was a “home studio revolution.” He rebuilt and rewired Stanford University’s world-renowned CCRMA facilities, with an emphasis on acoustic and electronic research. He modified Ampex tape machines, developed his own version of systems integration, designed motherboard chip sets for Intel, Analog Devices and others, and eventually turned everything he’d learned in electronics and transducer design into an expert consultancy that focuses on optimizing audio from the playback source—the content—regardless of the speaker at the output.

Quite simply, in the age of compressed, squeezed, bandwidth-dependent consumer audio, Paddock and his colleagues at Sound Research—based out of Lake Tahoe but as far afield as Russia and Austria—try to make everything sound better.

Electronics Meets Silicon

In one sense, the OMEN HDR soundbar can be viewed as a natural outgrowth of both Paddock’s career and the rise of Silicon Valley’s influence in the evolution of pro and consumer audio. Each is dependent on materials, electronics and digital signal processing, all of which have evolved dramatically and been integrated cohesively to create the modern recording/music industry. Paddock, you could say, with his rare left-brain/right brain symbiosis, was at the right place at the right time.

“I have been a musician my whole life, playing guitar in garage bands and all that,” he says. “I built my own amplifiers using tubes and transformers from Haltec Electronics. But I was also interested in aeronautics and materials—designing aircraft. My father was an FAA medical examiner, so the idea of planes was always around. I didn’t want to fly the planes; I wanted to design them. So at San Jose State, my concentration was in materials science/management and business.”

In 1976, while still in college, he founded Sound Research with the intent to “design best-of-class acoustics, using tuned speakers to create small studios,” a full decade before the “home studio revolution.” After graduation, he received offers to precept (equivalent to today’s internships) at Lockheed, United and Ampex. He picked Ampex. It was 1978 in the Bay Area. Things were happening. He already had a home studio.

“United was corporate, Lockheed was government and Ampex was incredibly interesting,” he recalls. “The materials science of Ampex tape recorders immediately captured my attention. Aircraft can’t fail, and all designers use backup systems—they have a Plan B. Audio products don’t have a Plan B. But Ampex was quite different. Their machines were built to last, they used the best materials, best power supply and best wiring, and they were incredibly rugged. The process, techniques and materials felt very familiar to me.”

He didn’t stay at Ampex following the internship, though he did learn a helluva lot about materials and became a certified expert in the company’s multitrack recorders. He took a day job managing Moyer Music, a hi-fi retail store in San Jose, and in 1979 he received a call from Ed Rudnick at E-mu Systems, who was building a synthesizer for Patrick Gleeson for use on Apocalypse Now.

“He said, ‘Come on up and I can get you a job at Different Fur,’” Paddock says. “Then 24 hours later I was the chief systems engineers at Different Fur working with Pat Gleeson. Francis Ford Coppola was in with Apocalypse Now. There was Richard Beggs, Tom Scott—all the top folks on the soundtrack. And I met Mickey Hart, who became the most influential artist in my life. Within six months I was hired by Mickey Hart to take care of his Ampex machines in his home recording studio.

“Mickey Hart has no limits,” he continues. “He’s boundless in his creativity. Every day Mickey has a new idea and he brings to bear his entire team on that idea. One day he decided that he wanted to mike the Golden Gate Bridge and let it sing. B&K sent a data recorder with some accelerometers. I provided some interface options. We set up the accelerometer, and before the police came we got stuff that Mickey could pitch shift into audibility. I stopped thinking about aircraft design.”

The Bay Area in the 1970s and 1980s was a hotbed of audio innovation. Building on the Ampex legacy and the birth of multitrack recording, coupled with the rise of computer-based applications, there were groundbreaking companies such as E-mu Systems, Opcode, Silicon Graphics, Sonic Systems, Euphonix and, eventually, Digidesign and Pro Tools, among so many others.

After a period of designing artist studios for the likes of Mickey Hart, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, David Bowie, Wyndham Hill and Brian Eno, Paddock designed custom stage playback systems for the Dead to put the band on wireless headphone-based systems to reduce stage volume. Out of that experience, along with further developments on The Beam, came the Reality Amplifier, which would form the basis of research and development for motherboards and chipsets in the coming years.

In 1995, Paddock developed a webcast-audio system for a worldwide tribute following Garcia’s death. Bandwidth was not there yet; fans let him know that the audio, quite simply, sucked.

So later that decade, Paddock formed a second company, Sonic Focus, and his second career, one based on consumer playback and optimized audio, was launched.

“Sonic Focus was born as a means to support low-bitrate content on the Web,” Paddock says, matter-of-factly. “The focus was on taking low-bitrate audio—say 32k, ATRAC by Sony, or 128k MP3—and create a soundfield that sounded as if it weren’t compressed. The goal was content enhancement, not speaker tuning. We didn’t worry about the transducer.”

In 2008, Sonic Focus was sold to ARC International. Paddock continued with his original company, Sound Research.

Partnerships and Playback

If Mickey Hart was the most influential artist in Paddock’s life, it was Intel that became his, and his company’s, most important technology partner. In 2004, Sonic Focus partnered with Intel to create Intel Audio Studio, which enhanced low-bitrate movie, music and voice content and also created 7.1 channels from stereo compressed audio streams. For the next four years, Intel Audio Studio shipped with all Intel motherboards. A later partnership with Analog Devices built on that technology to produce the chipmaker’s SoundMax audio enhanced boards.

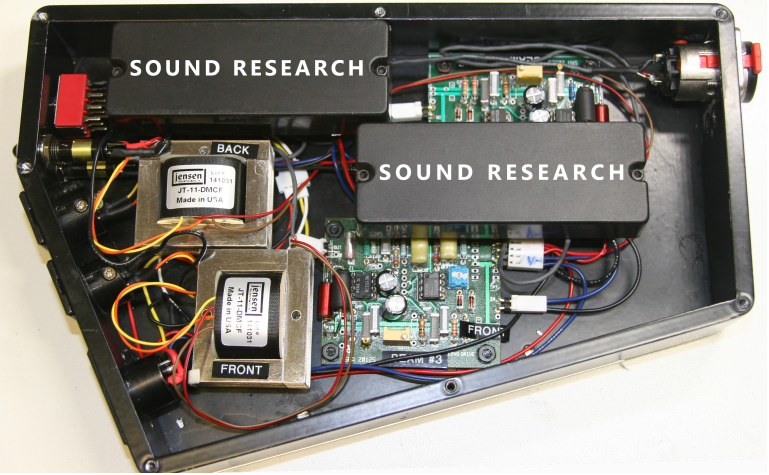

In 2013, in conjunction with Intel, Sound Research introduced the SoundEdge ERT, an extended range transducer that first appeared in the ROAR series of small speakers, and was later later leveraged in a 40mm by 25mm package in the 2017 CES Award-winning Dell XPS 27.

Around the same time, Sound Research had also partnered with Texas Instruments and its lead designer, Lars Risbo, who designed and developed the Smart Amplifier, later to be employed in Sound Research’s first real product with HP, and later incorporated into the OMEN HDR soundbar.

“The Smart Amplifier is unique compared to standard Class D amplifiers, in that it is designed to limit the RMS wattage of the speaker to limit thermal problems in the voice coil, but to allow the peaks to come through,” Paddock explains. “If the peaks are rounded off with a compressor, the audio sounds thin and dull and unnatural because of time distortion. But in a crest-enhancing amplifier, if the peaks are allowed through but the RMS or constant wattage is maintained, then the speaker sounds louder and more natural. Smart amps are very popular now because of the loudness and crest enhancement capability. TI and Sound Research pioneered that amplifier.”

Today, the Smart Amplifier forms the basis for the company’s developments with HP, starting with the popular ROAR speaker in 2013 and later incorporated into OMEN HDR. It’s an HP speaker, designed by Sound Research and the HP Industrial Design Group, headed by Jon Dory. The same team developed a custom curved soundbar for Stephen Hawking for use on his wheelchair, tuned and optimized for his voice, the way he thought he should be hearing it. Much of that research was parlayed into OMEN.

“The question every manufacturer asks is how loud can I make this product that I’m selling,” Paddock laughs. “Everyone loves bass, and everyone loves loud. Some people love clarity. Some people don’t know the difference. But everyone knows the difference between loud and not loud enough. The problem between loud and bass is that the louder you make a product, the less bass you can allow it to create. There’s a perfect relationship between loudness and bass and clarity, and it’s my company’s top goal to maintain low distortion with maximum loudness and superlative bass. It’s difficult to present all three of those criteria at the same time.

“We’ve been building products with HP for a decade, and the ROAR series was an indicator of our ability to enable HP with both tuning and speaker technology,” Paddock says. “We maintain maximum loudness using the Reality Amplifier. We maintain bass through the use of passive radiators and high-excursion transducers. And we limit distortion through proper materials design, proper enclosure design and damping resonance.

“Most soundbars use plastic. OMEN is a wooden enclosure and requires very little damping. Paul Kitano, our chief speaker ‘luthier,’ put together an optimized enclosure that is custom-cut out of wood—like building a guitar, but with a transducer inside an enclosure.”

The speaker bar was created in a modular fashion, with Kitano and team first developing a single speaker and a passive radiator. The OMEN HDR includes four of those modules to create width, depth and bigness. When listening, the stereo soundfield seems to fill a full 180 degrees, way above and beyond the screen. The bar itself was designed to be idiot-proof.

Keep It Simple

There is no subwoofer; Paddock doesn’t believe in them for the nearfield environment, where portability and comfort reign supreme. (Besides, the OMEN measures down to 40 Hz.” There are also only two inputs and two playback Modes. It’s designed to be plug and play.

“The most genius designs are the simplest designs,” Paddock says. “The goal was to eliminate as many controls as possible because our feeling is that users don’t actually want as much control as they think they do. In the end, they want to turn the thing on and they want the product to work. Give them too many modes and they’ll end up at the default setting. We have a Gaming Mode for games and movies, with an enhanced center image for voice and narration, and a Music mode, which is left-right and what you would expect.

“Likewise, we originally had three inputs on the OMEN—HDMI, optical and analog,” he continues. “I happen to think that HDMI on speaker bars is a bad idea for a variety of reasons, mostly involving changes in protocol and the introduction of new television sets and components that don’t conform. We found ourselves using the analog input more than the others, so we decided to build an excellent analog circuit using a Cirrus 105 dB A-to-D. It was good enough that we decided we didn’t need a digital input. Everything that works with analog headphones should work with the speaker. Gamers primarily use headsets, primarily wired headsets. So we built a spec for the speaker bar that would match a set of headphones. And it always works!”

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get it delivered right to your inbox.

Simple to use and quality in every detail. That’s the Sound Research approach in everything they do, from consultancy to design to output—remember, they don’t actually make the speaker, but they probably know speaker technology better than most manufacturers. They just concentrate on the smaller set, having lived a life among the bigger set. And there is much more to come, including consumer tuning and calibration tools, again, made simple.

You may not realize that you are experiencing Sound Research-optimized audio in your everyday life, from your PC to your tablet to your desktop speakers. But you likely are at some point in your day, and you’re reaping the benefits of decades of professional audio research applied to a consumer product. Much of the modern professional audio industry arose from the hi-fi world. Tom Paddock and his team are now paying back the debt and bringing quality audio to the home.

[Note: As of this writing, the OMEN HDR soundbar is only available with the purchase of the new HP Emperium 65-inch display. Let’s hope that changes. It will change your movie, game and music experience. Soundbars have come of age.]