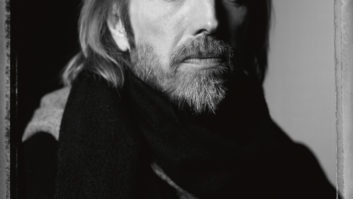

When Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers released their self-titled Shelter Records debut in 1976, few would have predicted that we would still be talking about the group nearly a quarter-century later. The album languished on the shelves for a full year before one track, “Breakdown,” became a hit and began a winning streak that has continued unabated to this day. Both with The Heartbreakers and on his solo albums, Petty has proven to be one of rock ‘n’ roll’s most consistent and enduring artists, with a knack for churning out timeless songs loaded with bright hooks and memorable riffs. The Heartbreakers have rarely strayed far from the sound of that first record, which deftly melded influences such as The Byrds, The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and Chuck Berry with Petty’s unerring songwriting instincts to craft a truly original group sound. The band’s approach to recording has been quite straightforward; Petty’s solo albums, such as 1996’s multi-Platinum, Grammy-winning Wildflower, take more chances in terms of arrangements and unusual sonics.

For The Heartbreakers’ latest endeavor, Echo, their first since She’s the One, Petty sought to keep the recording as simple as possible to capture the group’s powerhouse rock sound in all its glory. This is classic TP & The Heartbreakers all the way.

“From the beginning, we were kind of conscious that we didn’t want to do many overdubs on this record,” says Petty. “We pretty much tried to arrange everything down to where the group itself covered all the bases, and that was fun, really.”

Heartbreaker lead guitarist/co-songwriter Mike Campbell concurs: “Most of our work was in the songs and not necessarily in the recording process. The tracks are very live. There are some overdubs, but at least 90 percent of the solos happened during the live band takes. For example, with Benmont [Tench], our keyboard player, there was a lot of lifting the hands up off the keyboard and moving over to the organ, or stepping on a button, like you would do live, in the same recorded take. There is a lot of that element in the record; probably more than ever before.

“We’re turned on by playing,” he continues. “That’s where we come from, and that’s what we do. We had Steve Ferrone on drums and Howie [Epstein] on bass, me, Tom and Benmont. We had Scott Thurston, who plays with us live, play acoustic guitar on several tracks, and that was about it.”

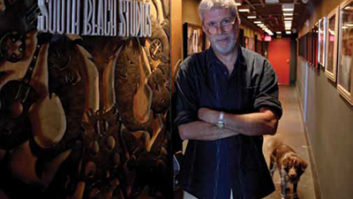

As with many of Petty’s recordings over the past ten years, much of the tracking and overdubbing was done at Campbell’s home studio, with Campbell doing much of the initial engineering. “This was a situation where we were going to go in and learn some songs and try them out,” he says. “I’m not really a trained engineer. I just kind of go by ear, but the tape was sounding good, so we put off getting an engineer or producer for quite a while, to sort of keep the vibe we had. This really isn’t a full-on professional studio, in the sense of a commercial studio. I’ve just got some gear in a room, and there is barely enough room in there for the drums. We just set up in there and put it on tape.”

In time, Petty and Campbell enlisted engineer/mixer/ producer Richard Dodd to record overdubs and mix the project. Then Rick Rubin was brought in to produce along with Petty and Campbell.

“Mike has three consoles,” states Dodd, “a small 12-channel Neve sidecar with old 1073s [preamp modules], which he purchased after I used it to track the Traveling Wilburys’ second album; a 24-channel Neve console with 1073s; and a Soundcraft 1600, which is the one that I mixed ‘Mary Jane’s Last Dance’ [a hit single off the group’s Greatest Hits album a few years ago] on. So Mike has 36 channels of 1073 and 24 channels of Soundcraft that he records through now. Just about every microphone that he wants to use has a dedicated channel strip, which makes the recording process for him quite simple once it’s set up. It’s just a case of selecting tracks, and off you go. He has enough outboard gear to support that, as well.”

Having worked on The Heartbreakers’ Into The Great Wide Open, the Traveling Wilburys and Petty’s solo Wildflowers, Dodd was no stranger to the band’s creative recording methodology. “Richard is a brilliant engineer and mixer. He really makes my life easier,” enthuses Petty. “I don’t have to worry about anything, because I know he is on top of it. He’s very in tune to singing, especially.

“Concerning vocals, I never do more than two tracks in a comp,” Petty continues. “The truth is that there is no reason do more than two, because you weren’t going to keep that [first one] anyway, right? You did something better than before. If I sing something better than I had, I keep that. But if I don’t, then I just try again. You can go mad with all of those comps laying around.”

Dodd shares Petty’s sentiment. “Today’s music is riddled with postponed decisions,” he says. “‘Let’s wait till later’ is the way most people think. It’s really hard to judge how good something is when you still haven’t decided on how bad the take was before it. It’s either right or it wasn’t. I prefer decisions over using up tracks.”

Although the recording of Echo was, by and large, a straightforward analog project, Dodd did use Pro Tools for fine-tuning and convenience in the mixing stage. “The whole time we were mixing, we had a full 24-bit Pro Tools rig that we rented at my facility,” says Dodd. “With Pro Tools, I was able to excercise options, like, ‘What about if this part happened earlier,’ or, ‘What if we AutoTuned that?’ Rather than guess, I would just try that edit and-bang! -done.

“I also saved a lot of backache on one song, where I wanted to re-amp a guitar,” he adds. “There’s a [Pro Tools] plug-in called the [Line 6] Amp Farm, where you just dial up one of the emulations of classic amps. It’s very entertaining and a lot faster than doing the real thing. Of course, we went back and plugged in the real thing, too, but the other way was just fine. It was very close.

“There’s one track called ‘No More’ that actually went to Pro Tools and then went back to analog,” Dodd continues. “We had a great take, but there was a place where the song sagged a little bit and they were going to recut. I just happened to mention that one of the things you can do with Pro Tools is edit and put things in time. So I went to this person who works out of the Mix Room, nicknamed ‘Blumpy,’ who was an expert at doing that. He’s an engineer, but he also has a reputation for being very quick and accurate at manipulating tracks in Pro Tools. He’s a very nice guy, and he did a great job. In fact, Rick Rubin said, ‘Why don’t we put the whole track in time, so we could find out what it was like.’ So Blumpy did it and it was a brilliant job. But we ended up using just the original four-bar fix he did.

“Interestingly, while he showed that he could ‘fix’ the tempo of an entire track, it also showed why the band doesn’t cut to a click on most of the songs. When the song came back ‘right’ or ‘fixed,’ with the same tempo throughout, it was a different song, so to speak. It was completely different. As much as Tom was impressed with how it could be and what it sounded like, the fix turned it into a pop song. The track, as it now starts on the album, starts on one tempo and ends on a completely different one, but it feels like it is the right thing to do. That is the way Tom wanted it.”

During the mixing sessions for the album, there was also considerable experimentation with different consoles to see which one suited the songs most. As Dodd explains, “I was given the luxury of taking one song to three studios. I mixed the song without using any outboard equipment or any EQ-just a faders-and-panpots-type deal. I emulated a balance in every studio. I even took the format that I was recording onto with me from studio to studio, so the only thing that changed was the multitrack source machine. I put the three mixes onto a CD, and I didn’t tell anybody what studio 1, 2 or 3 were. Everybody [Petty, Cambpell and Rubin] said they liked 1 and 3, which were either Conway or Village.

“I tried to trick myself by random-playing my CD, to find out which one would win. I came to the same conclusion. I liked 1 and 3. Finally, the decision came to Tom. He came in one day and said, ‘It’s number 1.’ So they looked at me and asked, ‘Which one is number 1, Richard?’ Well, that was Conway, with the SSL 9000.

“So we go to Conway, and I mix that same song for real this time, and it was great. I mixed another song there, and that was great. It was a similar-type song.” Dodd explains. “Then we moved to a song with a completely different approach sonically. It was more open musically, and it proved to be very difficult to mix.”

Dodd ended up mixing two songs on the 9000J; the remainder were done on a vintage Neve at the Village. “We pretty much have always used Neve consoles,” comments Petty. “I haven’t had much luck with SSLs for electric and acoustic guitars. I have never been able to get a mix on them. They just don’t come through sweet, like the Neve does for me.” Adds Dodd, “The Neve sounds a bit more ‘real.’ Drums are so transient that they seem to take on the character of the console. But I was surprised that it was guitars that showed up such a big difference.”

Another piece of gear Dodd was happy to make use of on this project was a vintage Fairchild limiter at Village. “Typically, I find them very good, but boring,” he says. “But they’ve got one that isn’t. This is the best one that I’ve heard in America. The first one that I heard that I liked was in London in Lansdowne Studios. They had a Fairchild there that made everything sound better. I’ve been looking for that one ever since. Every time I’ve come across one, however, it is like, ‘Oh, another boring old tube limiter.’ Village has one with the same magic as the one at Lansdowne. You just plug it right in and everything sounds better, even if it’s set to do nothing. Just going through it is magic.”

With most projects, Dodd gives himself a “challenge” to work toward. “I almost always do something like, ‘On this album, I won’t use any 1176s,'” Dodd says with a laugh. “I might not tell anyone, but I do that to prove to myself it can be done. I might say ‘no Neves’ or ‘no Shures.’ For this album, we went for no 2-mix processing. We didn’t use 2-mix processing on more than half of the album.”

On Wildflowers, Dodd set out to mix the album with no automation, and out of 23 tracks, he used automation on only five, and only two or three ultimately ended up on the album. “For this album, though, I knew I wanted to use automation,” he says. “The reason being that I wanted the facility of having some of the mutes automated, so I could turn off some spurious sounds. Benmont would simultaneously play the acoustic piano, Hammond organ and chamberlain, with foot switches and pedals going. He’s got his method down, but that meant that, if he had to stamp on a switch or something, and the mics are still open for the piano, which are going to the same tracks, you are going want to, if possible, get rid of that click without destroying the feeling. If that happens at the same time you have a vocal ride to do, then it is nice to have the automation.”

Asked if there were any tracks that have emerged as favorites, Campbell quickly replies, “I like this song called ‘Room at the Top’ and a song called ‘Counting on You.’ ‘Room at the Top’ starts sort of quiet and gets really loud; it’s hard to describe it. There’s a lot of drama to it.”

“Like Macbeth,” interjects Petty dryly.

“Yeah, like Macbeth, Tom says,” Campbell laughs. “How do you describe a piece of music? You just have to listen to it. It just sounds like us playing.”

“There’s a lot of dynamic and variance in the tone and attitude of this album, but it’s just all played by a rock group,” says Petty. “There are no loops and stuff. It’s just us playing, which I think is becoming more and more rare.”

“At this level of recording, you can do whatever it takes to get the best result,” Dodd concludes. “‘Which system shall we master to?’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘Well let’s do all of them.’ That’s the luxury. When you put together the cost of the rental equipment, the cost of the studios and everything else, Tom certainly hasn’t scrimped. But at the end of the day, it sounds like they just went in and played it, and that’s a high compliment. I think that is what the goal was. They played until they got it right. It was all about getting the right mood and the right feel.”