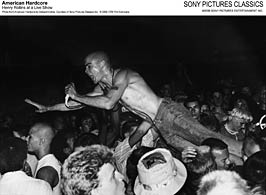

Henry Rollins crowd-surfing during a Black Flag live show

Photo: Edward Colver. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics Inc. © 2002 CTB Film Company

In our current era of safe, blow-dried, corporate rap and rock, and super-bland pop, the snarling, spitting, angry punk acts profiled in the new film, American Hardcore: The History of American Punk Rock 1980-1986, come across like a musical speedball — dangerous, manic, provocative and obviously in league with the devil. Want a little political commentary on President Reagan? Here’s D.O.A. smashing their way through “F***ed Up Ronnie.” Think only disaffected white kids from the South Bay related to punk? Well, here’s Bad Brains, the all-African-American outfit, kicking some serious ass, along with such seminal bands as Black Flag, Circle Jerks and Wasted Youth.

Based on the book American Hardcore: A Tribal History by Steven Blush and directed by Paul Rachman, a top music video director who began his film career making underground hardcore punk films and music videos for bands such as Bad Brains, Gang Green, Negative FX and Mission of Burma while he was still in college, the film examines the influential punk subculture using a mix of more than 100 interviews, original performance footage and rare archival material. It does justice to its subject matter by purposely not polishing its visuals or offering a spotless aural landscape.

“The music was all about energy and aggression and anger, and I wanted to preserve that raw, primal scream,” notes Rachman. “So when it came down to all the problems we had with audio, I didn’t want to lose all the rough edges anyway. I wanted it to match the whole punk approach, which was basically D.I.Y.’”

With this in mind, Rachman and Blush self-financed the film and started shooting interviews for the project at the end of 2001, and then spent the next four-and-a-half years chasing down the musicians. “Even though we’re friends with many of them, it was hard finding them and then getting them to sit down and talk,” Rachman admits. “Most are still on the fringes of society, and usually where we met was far from ideal for recording audio. We had to deal with everything from A/C hum in a warehouse to strong desert winds when we shot on location in Joshua Tree [Calif.]. But it’s a documentary and you just go for it.”

Rachman used two cameras — a Sony VX 2000 and a PD 150 — with a Sennheiser EW100S lavelier wireless system and a Sennheiser 64 shotgun. “I kept it simple for the field work, and my crew was just me on camera and Steven holding the boom,” he says. “We did all the interviews with shotgun in channel 1 and the wireless in 2, and whenever we had to interview two people, the primary one would get the lav and we’d move the boom between them.

“As for all the performance and home video footage, we had to deal with so many different formats,” Rachman continues. “I had a lot of material I’d shot back then using ¾-inch video or U-matic, and there’s even stuff on third-generation VHS, recorded in SLP mode, as those were the only masters we could find of some of these shows.”

American Hardcore director Paul Rachman, left, and writer Steven Blush

Photo: Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics Inc. © 2002 CTB Film Company

He also had to deal with a kaleidoscope of different audio formats. “Even some of the records from the early ’80s were recorded in a noisy basement on a 4-track cassette recorder, barely mixed and then put out on vinyl,” he adds, “and those were some of our key sources. So I knew there was a certain raw element to the sound, but I also felt I could make it all work artistically in the context of the subject matter and story.”

Once all the collected footage had been transferred to Digital Betacam, “We transferred back down to DVCAM and MiniDV for the offline edit,” Rachman says. “And I had an Avid Xpress Pro system that was totally portable, so even when we were moving around, I had my laptop and I could digitize from the camera onto the computer and keep organizing material as we went. So we started the early stages of editing while we were still filming.”

By last year, Rachman says the editing “was getting serious. Our first cut was six hours, and gradually we got it down to the current 100 minutes and got it finished in time to screen at Sundance this year.”

For that cut, he did a mix in the Avid. “Our interviews were on MiniDV tapes, and a lot of our music came from CDs of the original vinyl recordings, or the vinyl itself, or raw, live VHS tape with just a camera mic at these live shows,” he explains. “I had about eight channels of sound in the Avid, and I’d just keep my CD or vinyl sources on certain channels, just so I knew where the audio was coming from originally. That way, when I created the OMF, I could tell Robert Fernandez, the mixer at Sound One, what he was dealing with.”

Once he’d locked picture for Sundance, Rachman did online using Symphony at Sony Music Studios in New York, and Fernandez then took the eight channels of sound and imported them to Pro Tools. “Again, we kept it simple,” he adds. “I told Robert, ‘We’re dealing with a lot of very raw sounds here. All the formats sound different, and nothing was ever engineered and mastered to any recognized specs. There are no industry standards here at all. So let’s preserve that rawness and visceral roar in the final mix.’”

A flyer for a Bad Brains (guitarist Dr. Know, vocalist H.R., bassist Darryl Aaron Jenifer and drummer Earl Hudson) gig.

Photo: Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics Inc. © 2002 CTB Film Company

Rachman also stressed the importance of “the sheer volume” of the music. “I’d go to all these punk shows in the early ’80s, and they’d be in some weird hall or basement club, where the acoustics were pretty bad and the bands always played at an ear-piercing level,” he notes. “It was always so loud and intense, and I felt it was crucial to maintain that in the film. I wanted people in the audience to feel what I’d felt in those clubs — the sheer assault of the music. So I told Robert, ‘Keep it loud and try to balance it enough to keep that intensity.’”

Sound editor and re-recording mixer Fernandez, a 16-year veteran at Sound One, says that he had his work cut out for him: “We only had four days to do the mix, and I had to edit and mix at the same time. It was all done using Pro Tools 6.94 and ProControl, and I set up about six dial-up tracks with a Focusrite compressor on each one as an insert. Then I found settings that would work.”

Because of the raw sound and audio problems with a lot of the interview segments, Fernandez relied heavily on the Waves Restoration package, “with a lot of EQ’ing and filtering. As for all the music, I tried to make it all sound as good as I could, so I listened to the first 10 cues and tried to find the best recording quality.”

He then went back and matched the rest of the music to those cues, using some outboard gear in a few instances. “There’s a great old analog box, the AN2, which I used to make a stereo image out of some of the old mono recordings,” Fernandez explains. “There was also a lot of distortion on some tracks, so I used the Waves De-Crackle plug-in, which really helped, and I also used a lot of the C4 plug-in, which is a very nice noise-reduction program. So by using all those little tricks, I was able to keep the sheer power and raw quality to the audio that Paul had discussed with me.”

After his pep talk and during the mix, the director checked in with his sound mixer “a couple of times and gave him minor notes,” Rachman remembers. “He was on the right track right away, and it was very simple — although sometimes simpler is harder. He didn’t have a lot to work with. There is no layering or effects. There is no ambience. There’s not even any crowd footage mixed in to dress it up. It’s just pure, simple sound.”

For the Sundance cut, Fernandez made an Lt-Rt mix. “It’s not a Dolby mix, but basically a stereo mix for film because at Sundance we screened on HDCAM,” adds Rachman, “and at Sundance they only play back Lt-Rt off HD. There’s no Dolby decoding there.”

After the film was well-received at Sundance and got picked up by Sony, the team went back to Studio One and did the final 5.1 Dolby mix, “with hardly any changes to the original mix — maybe two cues,” says Rachman.

“When I set out to make this film, I wanted to make more than just a rock documentary,” Rachman says. “Hardcore punk in America was also a social movement, and so I also wanted to give the music that context. That’s why it starts with a minute of newsreel footage from the ’80s. All those images take you back to that era, and then the music kicks in and takes no prisoners.”

Iain Blair is a freelance writer in L.A.