During his 15 years in Los Angeles, the versatile composer Alex Wurman, who deftly and seamlessly integrates traditional orchestrations, electronic elements and small ensembles, has graduated from AFI student films to such disparate cutting-edge features as Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, Thirteen Conversations About One Thing and the Oscar-winning documentary March of the Penguins.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Wurman, who drew the biggest raves of his career for his work on Penguins, was born to the role of freewheeling composer. The Chicago native is the son of Hans Wurman, a composer and arranger who pioneered the fusion of classical and electronic music, at one point painstakingly transcribing orchestral works by Chopin, Bach and others to his Moog synthesizer, which bore the designation Serial No. 2. His son started acquainting himself with the prototypical synth as soon as he could reach the keyboard, at the tender age of 5.

“My first experiment,” he recalls, “was to use a square wave tuned so low that you could hear the pulses between the cycles and gradually speed it up with the frequency knob to create the sound of a tank, which I envisioned driving.” As his parents were divorcing, Wurman, then in high school, slipped away to the South Side of Chicago, where he spent more than three years playing keys with funk and blues bands. No wonder he’s equally comfortable working with 80-piece orchestras and soul grooves.

Wurman was best known in film music circles for his work in comedies such as Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy and edgy scores like that for the 2004 neo-noir Criminal before revealing a new dimension of his art with the crystalline, captivating music he created for March of the Penguins. “A lot of people feel that Penguins is an orchestral score,” says the composer, “but more than 50 percent of it is electronic, and the electronic aspects were not created to mimic an orchestra. I did not use orchestral samples, but I did write some of the synthesized aspects of the score in an orchestral way.”

Penguins‘ score “represents the beginnings of a style I aspire to be known for,” he says. “It’s a hybrid score, but first and foremost, it represents what I feel is cohesive, harmonious music that’s good for the soul. It’s good for my soul; it makes me happy. The score for Criminal, while it’s funky, makes me want to go out and rob people. If I had to choose between the two, I would choose the passion that went into Penguins as opposed to the sinister qualities of Criminal. I’m very pleased, of course, to be given the opportunity to do both.”

It’s this versatility that is the basis of the 39-year-old composer’s ever-growing reputation. When asked if he has a signature style, Wurman replies, “I think what’s emerging out of all this is a tendency to play with rhythms in a similar way, no matter what the genre is; multi-meters — I really enjoy things that are happening simultaneously. I’m also starting to figure out how to get my harmonic tendencies into whatever it is I’m doing. And that is to have a set beginning, middle and end, which is how you get someone to actually feel an emotion — you have to carry them to that place. March of the Penguins is a good example because I had the time in the film to do it. That’s when I’m going to be known as being valuable — when I’m given the time to take somebody to where it is they want to go.”

Photo: Jerome Maison; Copyright 2005 Bonne Pioche Productions

Scoring films is an intricate exchange between the composer and the filmmaker. As an example of the sort of interaction that takes place, Wurman cites his work with filmmaker Adam McKay, whose idiom is comedy — he directed Anchorman and the summer 2006 release Talladega Nights, both starring Will Ferrell and featuring Wurman’s music.

“Writing the score for a Will Ferrell comedy directed by Adam McKay is a unique experience because its sensitivity to the application of the music is extremely high,” says Wurman. “It’s one parody after another, and often they’re joined together with seconds to spare. The juxtapositions can be very fleeting, yet very important, because if it doesn’t work, it can ‘step on the funny,’ as they call it. Trust me — everything in the music for that movie is humorous. If you’re hearing something serious, it’s funny. In a way, the music, instead of making you laugh — which is often the case with this music in this movie — is building the story.”

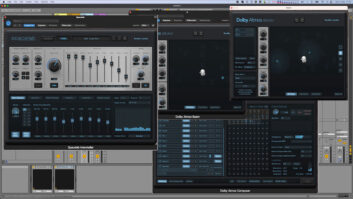

For Wurman, creating music for a specific project involves both aesthetic and practical considerations. “It begins with watching the film, and at the same time, I’m coming up with creative ideas; I’m looking for creative solutions to whatever time or financial problems the film might have or any of the needs the film has that might rub up against each other,” he explains. “Then I start fantasizing about the instrumentation as a result of that budgetary perspective and the creative perspective at the same time. I’ll start to hear melodies and harmonies, sit at the piano and flush them out, and then I’ll go into my studio and start slapping them up against the picture.

“A lot of what I do with synthesizer production remains in the final score,” Wurman continues. “I use software and hardware synthesizers, including Apple’s Logic Pro — they’ve got some cool synthesizers in there. I love Spectrasonics products because the loops and other instruments have such a great quality and ease of use to them. If I decide to use one of those sounds, I’ll usually build the track around that. On Talladega Nights, one cue in particular has very heavy Spectrasonics drum stuff in it. And when I recorded that 80-piece orchestra over it, we ended up going with the very dry and percussive approach to the orchestra to help bring it closer to that sonic quality of the Spectrasonics sounds. That’s a really fascinating way to go.

“The great thing about using a host of different instruments,” he notes, “is that the programming that goes into them is done by different people, so each instrument has its own characteristics. I have a nice old Yamaha KX88 controller that I use to control all my soft synths and [Tascam] GigaStudios.” Wurman’s arsenal of electronic instruments includes a Waldorf MicroWave XT, a Roland JP8000 and, fittingly, a Minimoog Voyager.

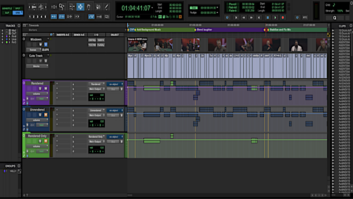

“So, I’ll take those live tracks and synthesized tracks in Pro Tools and go off to a recording studio to do the orchestras,” Wurman continues. “On Talladega Nights, I used Joel Iwataki, who I think is a genius, to record and mix. We went to Warner Brothers to record and we had 80 pieces — a large number for that room. If an orchestra is playing really loudly, you can overpower the room if it’s not big enough, but Joel has a technique that worked perfectly. One cue was big and strident-sounding in the beginning, and I wanted the second half to sound very Baroque and near-field, so we just did it with spot mics, and it turned out really well.”

In a sense then, a finished score is the result of a series of collaborations. “What I love most about movies,” he says, “is that I’m not only collaborating with fantastic musicians, but we’re given a set of guidelines that focuses everybody on the prize. We just get down to business, and it leaves no time for any sort of deliberation. And then there’s all this wonderful collaboration with the filmmakers, who are coming from a place that’s so valuable because it’s an emotional place that is not musically convoluted. I love having that inspiration from them.”