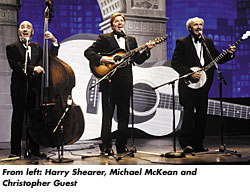

A Mighty Wind won’t save the music industry, but it willdefinitely provide it with some much-needed laughs. Remember the folktrio who opened for Spinal Tap in actor/director Christopher Guest’sbeloved 1984 mockumentary? Well, they’re back. Twenty years later, withmore pounds and less hair, still being, as Michael McKean, SpinalTap/The Folksmen guitarist describes, “not reallyincompetent…just kind of tasteless.”

Guest went on from acting in This Is Spinal Tap to write anddirect Waiting for Guffman and Best in Show, both oddlyendearing films that demonstrated his unique ability to skewer withcompassion. Now, Guest has turned his attention back to the musicindustry, specifically, self-righteous folksters of the ’60s.

The setup: When Irving Steinbloom, the Bill Graham of folk music,passes away, his family stages a reunion tribute concert featuringthree of his biggest groups: The Folksmen, Mitch and Mickey, and thenine-piece (or “neuftet”) New Main Street Singers.Interviews are interspersed with flashbacks and rehearsals, allculminating in a live concert filmed at Los Angeles’ Orpheum theaterand recorded by Le Mobile.

For Wind, Guest brought back his regular acting ensemble,including co-writer Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, Fred Willard andJohn Michael Higgins, along with music producer C.J. Vanston, also aveteran of both Guffman and Show. This time around,Vanston had his hands very full, because, well, the actors in the moviehad to play their own instruments. The catch? Many of them didn’t knowhow before they got involved in Wind. In testimony to the powerof great acting, they not only learned to play and sing, but some ofthem also penned tunes for the film.

Vanston has played live with Spinal Tap for 11 years, so he’sfamiliar with The Folksmen — Guest, McKean and Tap bassist HarryShearer — who are actually, in real life, excellent musicians whohave played together for over 20 years. “They opened forthemselves at Spinal Tap’s Carnegie Hall show, and the audience didn’trecognize them,” Vanston says with a laugh. “The reactionwhen people realize who they are is one of the most amazing things I’veseen in show business.”

Prior to filming, approximately 25 songs were recorded over a periodof 14 months by Vanston and engineers David Cole, Charlie Bouis and EdCherney. Those songs make up the film soundtrack and the soundtrackalbum (out on T Bone Burnett’s DMZ imprint).

“We started by hooking up the actors with teachers so theycould learn their instruments,” recalls Vanston. “Then wegot them rehearsed, and arranged and recorded all the song demos. Inall, there were 17 musician/actors who also did all the singing andharmonies.”

The journey began at Leeds Rehearsal Studios in North Hollywood,where Bouis, who also works with the Le Mobile remote truck, has arecording studio. The actors set up on a stage and began recording andvideotaping rehearsals. “What was interesting,” commentsVanston, “was that their acting skill transcended so much. Beingsuch good actors, they were able to commit themselves totally to themusic; even more, in some ways, than a lot of the musical artists Iwork with.”

Actor Higgins, who portrays one of the New Main Street Singers, isin real life a connoisseur of the Swingle Singers, Up With People-stylemusic that the Main Streeters’ songs were based on. He became the vocalarranger for those cheerfully overwrought cuts, which were among themost difficult to record.

Bouis’ Pro Tools and Yamaha DM2000 setup came in handy. “Wegot the band onstage, put them in position and began experimenting withmiking, because they didn’t want to see a lot of the mics,” heexplains. “I put up something like three Neumann 87s to cover thewhole band and a couple of close mics that were hidden. We wanted tosee what kind of recording we’d get if we had to make it look like anold-style recording. But we knew that when it came to mixing the film,C.J. would want some control over the individual instruments. Wecontacted Shure, and Jack Kontney and Tom Krajecki helped us out withtheir WL50 lavalier mics and also PSM 700 wireless in-ear monitorsystems.”

After rehearsals, recording moved on to Vanston’s Treehouse Studios.“We kept it tube-sounding,” says Vanston, who records inEmagic’s Logic Version 6. “We used all the ‘Gucci’vintage mic pre’s for recording, particularly Neve 1073s and myUniversal Audio 6176, which is a killer box. We transferred thoughApogee DA 16 converters to analog for the mix [by Cherney at TheVillage], then to Pro Tools for the dubbing stage.”

The climax of the movie is the concert, filmed in front of 700extras. The Shure lavaliers were an essential component, mounted on thebridges of everything from upright bass and banjo to autoharp.“There were about 20 musician mics and eight mics for audiencereaction and ambience,” says Bouis, who worked the show with LeMobile’s Ted Barela and Ian Charbonneau. “We used SM 58s for theregular vocal mics, and just about every person also had a lav mic thatwe taped on guitars, kind of hidden. As they are really tiny-profilemics, we could do that. It worked really well, because it enabledflexibility in the mix to match up sounds with the visualfocus.”

Vanston gives high marks to music editor Fernand Bos of LowdownMusic, who matched up the myriad music takes to picture, something that— due to the novice musicians — had to be particularlychallenging. (Did we mention that Guest works from outlines, ratherthan scripts, and all dialog is improvised?)

“Chris’ movies have a very evolved kind of humor,”concludes Vanston. “It’s very gratifying to work on somethingknowing people who see it are going to laugh and have a good time. Itwas a ton of work, but it doesn’t come off that way. And word’s gettingout; yesterday, I got an e-mail from the Kingston Trio inviting us to acookout and asking us to bring our guitars!”