| MIX VERDICT: JH AUDIO PEARL + RUBY IEMS |

| THE TAKEAWAY: “The price of the Pearl + Ruby system is not exorbitant, but right now it’s probably out of reach for all but A-level tours—and the fidelity is certainly worth the entry fee.” |

| COMPANY: JH Audio • www.jhaudio.com PRICE: $3,500.00 (generic fit); $3,700.00 (custom molds) PROS: • Very high-quality sound. • Preset “signatures” enable a monitor engineer to more accurately hear what a performer hears. • Extremely low-latency processing. CONS: • Amplifier pack adds background noise. • Software is Windows-only. • Pack doesn’t show charging status unless powered on. • Documentation leaves something to be desired. |

New York, NY (June 28, 2024)—The JH Audio Pearl + Ruby IEM system is a premium in-ear monitor setup unique among currently available IEMs. Unlike traditional in-ear monitors, Ruby earpieces have only a passive low-pass filter internally; all other crossover functions are handled via DSP built into the companion Pearl Processor, a tri-amp beltpack constructed by Pearl to JH Audio specifications.

As a result, audio quality of the Ruby earpieces is reliant upon the Processor. The Ruby headphone cable is terminated with a locking, 10-pin ODU connector that mates with the Processor, so the earpieces cannot be used with conventional 3.5 mm audio outputs, nor can the Processor be used with other IEMs. It’s a system.

The Pearl Processor is described as a “micro speaker management system designed for IEMs,” employing DSP at 96 kHz (future firmware updates will enhance this to 192 kHz). It utilizes an actively controlled passive crossover, which—according to the company—can reduce latency to levels between .60 and .80 milliseconds. When combined with the latency of a typical digital console (around 1.5 mS), and an IEM system (1 mS), total IEM system latency using the Pearl + Ruby is still under 5 mS, which is critical in live performance applications. The Processor’s DSP does this by fine-tuning the crossover parameters, EQ and time alignment between Ruby drivers without use of an active low-pass filter, which would otherwise increase latency beyond acceptable levels.

The Processor is controlled by the use of three applications: Pearl GUI, Pearl Loader and Pearl Updater. GUI enables users to control gain, phase, time alignment, equalization of low, mid, and high frequencies, and levels for low-, mid- and high-frequency drivers of the Ruby earpieces. This itself is a game-changer because independent adjustments for the left and right earpieces allow compensation at the component level for differences in hearing between a listener’s left and right ears, with much more precision and repeatability than simply EQing the bus output from a mixing console (more on this later).

These settings can be saved and loaded into the Processor using Pearl Loader. A library of preset “signatures” are available for auditioning and uploading to the Processor. Some of the presets, such as “Ruby Auratone” or “Ruby Focal Twin6 B,” mimic the sonic signature of popular monitors, while others provide subbass enhancement or flat response curves that may be used as a jump-off point for creating your own presets.

The Processor holds one preset at a time, so Loader is required when you want to change presets. Updater is used only for loading firmware updates to the Processor. [Editor’s note: As of this writing, the applications run only under Windows; JH Audio is working on software for Mac that should be available this summer.] Our Pearl + Ruby system shipped in two boxes. One contained the earpieces and cleaning tool, while the other contained the Processor; a USB thumb drive holding the software, a library of signature files, and a manual on PDF; a short USB Type A to Type C cable; and a 3.5mm-to-3.5mm jumper cable, which is required to patch audio from the output of an IEM system into the Processor. The manual supplied was version 1.0 and left a lot to be desired; a revision should be available by the time you read this.

I used the system with both generic-fit and custom, molded earpieces, and while I found that the generic versions fit my ears better than most generic earpieces, I used the custom molds for the majority of the evaluation.

PEARL PROCESSOR

The first Processor I received was a bit temperamental. I had trouble getting it to connect consistently to the GUI (albeit running Windows on a Mac under Boot Camp), and at one point, it locked up. I did not care for the implementation of the power button, which was difficult to press. This was replaced with a second Pearl Processor, which has been playing happily with my Mac for weeks and has a power button that’s easier to use.

The Processor is a solid little unit at approximately 3 x 2.5 x .75 inches. At the top of the pack are a 3.5mm audio input jack, a three-color input-level LED and an ODU jack for the Ruby headphone cable. The side panel features a status LED, USB Type C port for charging and programming the Processor, and the power switch. A belt clip can be found on the rear panel. There is no user access to the rechargeable battery, which runs up to 10 hours on a full charge. Construction of the pack is very well done. It feels solid and the finish speaks to its pedigree, though, depending upon the viewing angle, I did find it difficult at times to discern whether the status LED was yellow or green.

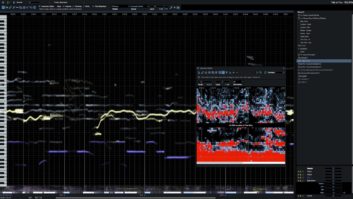

Opening the GUI displays a main screen with individual left and right faders for Input, Low, Mid and High bands, with phase, mute and gain for each. Tabs at the top of the screen provide access to the Low, Mid, and High bands, while controls at the top right allow you to sync the software with the pack, save the file as a preset, or load a preset signature file. When the Processor is synced to the GUI, the Status window shows “Connected” in green, and the faders will snap to the values saved in the preset.

Prior to diving in, I simply used Loader to audition the supplied preset files. Changing from preset to preset, I could clearly hear the different audio signatures, and while some may tickle your tastebuds, all of them show off the audio quality of the Rubys. Processor notwithstanding, the Rubys sound fantastic. The midrange (vocals in particular) is smooth as silk, high end is clear and extended, and bottom end (depending upon the preset loaded) can almost fool you into believing there’s a subwoofer hidden somewhere nearby.

It’s also apparent that amplification in the Processor is first-rate. When driven to levels louder than I’d care to monitor, the system never sounds like it’s running out of gas (though the Processor adds some background hiss). As such, the Rubys can definitely serve as reference monitors in a mixing application.

INSIDE THE GUI

The Low, Mid and High screens are where you can adjust EQ, filters, delay and levels for each band. Controls for Low include two bands of parametric or shelf EQ, high-pass and lowpass filters, and delay. Mid offers four bands of parametric, EQ, high-pass and low-pass filters, and delay. High provides six bands of parametric EQ, plus high-pass filter and delay. EQ and delay can be ganged, but the faders cannot. Initially, I found this amount of control a bit intimidating, but keep in mind that if you dive down the rabbit hole, you can always come back to the preset library to bail you out.

I started with a preset called Ruby Live Flat Bass .86 Latency, tweaked the Low faders up a few dB and headed for the rehearsal room. Patching my electronic drums into the Ruby was an ear-opener— especially in the bottom end, which was full and solid. It’s possible to adjust the delay of each band (up to 10 mS) with accuracy within a fraction of a microsecond, which changes the phase response of the Ruby as well as one’s spatial perception of the audio. Delay values are entered in milliseconds, so typing “1” results in a delay of 1 mS. Setting the delay under 1 mS requires typing “0.X,” and you can’t click in the field and drag to change the delay time. I nearly always deferred to the settings provided with the presets.

While the amount of control over the EQ and phase response of the Rubys may sound like a novelty, there’s something far more important to consider: The ability to alter the response of the earpieces can be used as a means of “leveling the playing field” between a monitor engineer and performer.

Jerry Harvey himself was kind (and patient) enough to relate to me his recent experience of being dragged out of retirement as a monitor engineer to hit the road with an international artist. Audiograms (essentially the frequency response of a person’s ears) were made for each performer on the tour, as well as for the monitor engineers. Knowing the hearing characteristics of a particular performer enables an ME to understand and compensate for the performer’s hearing losses.

That’s not to say that if, for example, a guitar player has a 6 dB notch in their hearing at 2 kHz, one can simply fix it by using the GUI to create a preset with a reciprocal curve—it’s a far more subtle process than that. But at the very least, it gives the ME a better understanding of what a performer is hearing and why.

Furthermore, given an audiogram of the monitor engineer, it’s possible to create presets for each performer that reconcile the differences in hearing between the ME and the respective performers—and that’s a game-changer. JH Audio is also working on presets that mimic other IEMs, which means that a performer can use the IEMs of their choice, while a monitor engineer uses a Pearl + Ruby system running a preset that simulates the behavior of the performer’s in-ears, making it easier for the ME to understand and address the performer’s IEM mix.

Looking at the Pearl + Ruby from a global view, I see three distinct applications: They can be used as a portable high-end monitoring platform that translates to a variety of popular studio monitors; they can be tailored to a listener’s taste regardless of their hearing profile, and they can promote consistency in a monitoring system between performers and their monitor engineer(s). That’s an awful lot of power to wield, and it requires that users have a thorough understanding of how to apply compensating curves to “fix” a listener’s hearing experience.

The price of the Pearl + Ruby system is not exorbitant, but right now it’s probably out of reach for all but A-level tours—and the fidelity is certainly worth the entry fee. Hopefully the technology will trickle down to more affordable price points in the future so that a wider audience can reap the benefits. Kudos to JH Audio for pushing the limits of IEM technology.