An old road buddy in England recently posted a photo on Facebook of a massive analog mixing console sitting at front-of-house surrounded by four or five racks of outboard equipment. “Proper setup, that,” he wrote. Perhaps so, but touring productions that can afford to carry consoles that occupy valuable seating space and require six or eight pairs of hands to tip into place have become something of a rarity in the economic reality of the past 15 years.

“We started in 2006 with two semis and three tour buses, with 32 people on the road,” says Glynn Wood, who signed on as both front-of-house engineer and, initially, production manager at the beginning ≠of the Zappa Plays Zappa project, on which Dweezil Zappa re-creates the music of his father, Frank, with a band of top-notch musicians. “Then the 2008 recession devastated the music industry. Our audiences just disappeared—and it wasn’t just us.”

“That led to the situation today where it’s the two of us,” interjects monitor engineer and production manager Pete Jones, during rehearsals for the upcoming Via Zammata tour, which begins May 3, promoting Dweezil’s first solo album project in a decade. Jones, who has toured with the Radiators, Big Elf and Tal Wilkenfeld, frequently mixes at Tipitina’s in New Orleans, where he spends a lot of time. He initially joined the Zappa crew in 2007 as drum tech for Joe Travers and Billy Hulting, just in time for Terry Bozzio’s final show with the band, before taking over production/tour management duties in 2010. “Dweezil did his best to keep the majority of the crew and band together in 2008 and 2009, despite the economy failing,” says Jones. “At that time we both loaded and unloaded the truck, I tech’d every instrument onstage, I tour and production managed, and did monitors. And sang a song in skintight spandex and a wig, as David Lee Sloth,” he laughs.

In late 2015 the two engineers were approached by Waves to road test a brand new product, the eMotion LV1, an innovative mixing system that uses a pair of large multi-touch screens in place of a traditional console surface. The system is extremely compact, Wood reports. “Now, we all fit in one bus towing a trailer. And with the LV1 system we have lots of spare room in the trailer.”

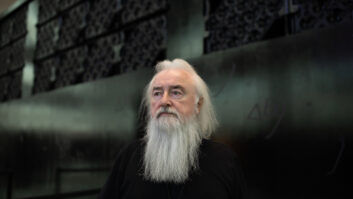

Engineers might balk at the thought of mixing on a glass panel, but Wood, in his early 60s and with four decades of experience on the road with artists including Sinead O’Connor, Suzanne Vega, Big Audio Dynamite and Vanessa Mae, is proof that you can teach an old dog new tricks. “As many fingers as I have, I can do that many things; I could raise 10 faders all at once,” he says. “Anything I touch reacts immediately and is solid. One thing you need to be careful of is that on a touchscreen monitor you can inadvertently touch something else and alter it. But I’ve trained my fingers now. It took me two or three days; it was not difficult.”

Waves brought in engineer Stephen Bailey to help train the Zappa crew. “He is a master of this system,” says Wood. “We were using the system three months before the release version, and I’m very proud and honored to have been a part of the beta process. Waves immediately worked on anything that has given us any problems. But the only real problems have been GUI interface things; the audio has remained perfectly solid.”

Perhaps more importantly for the minimal road crew (there is also a backline tech), the system has significantly reduced load-in and load-out times, and effort. “It’s so fast to put together,” says Wood. “The only things that I plug in from the outside world are the mains, my two flat screens, which have HDMI and USB 3 connections—so three connections per screen—and my Ethercon snake. It literally takes me four minutes to set it up.

The only other equipment that Wood has at FOH is a 16U rack: “In the rack are an IOC and an IOX, which are my local DiGiGrid I/Os. Below that is an output patch, two Waves SoundGrid Extreme Servers, one of which is redundant, and the computer.”

But how does it sound? “It’s above and beyond anything that I’ve worked on in the past,” Wood reports. “There’s nothing to touch it sonically. The DigiGrid I/Os are fantastic; the headroom is fabulous. It’s the best sonic experience you could have.”

FOH engineer Glynn Wood at the new Waves eMotion LVI mixing system, in rehearsals for Dweezil Zappa’s Via Zammata tour. Photo: Steve Harvey.

The FOH and monitor systems are both loaded with Waves Mercury plug-in bundles, but Wood comments, “If I didn’t have the entire Waves bundle I could perfectly easily work with just the eMo plug-ins” that come with the LV1 system. “As soon as we load the software it loads every channel with the D5 [Dynamics] and Q4 [Paragraphic EQ]. They are so good; zero latency. It uses no processing power, but every single knob, dial and switch on the dynamics does exactly what it says it does, and it does it really well.”

Among Wood’s go-to plug-ins in the Mercury bundle is the SSL G-Master Buss Compressor. “It glues your mix together and does it really well. The C6 Multiband Compressor is also a fantastic device. I can’t say that I have a particular plug-in that I can’t live without. If I did it would probably be the D5. It does everything, and supremely well.”

The LV1 system supports up to 128 inputs at sample rates from 44.1 kHz through 96 kHz, with eight plug-ins per channel and bus. “One of the songs that we’re playing off Dweezil’s new album, a track called ‘Rat Race,’ has a very affected vocal. I probably have five or six plug-ins to generate the sound that he developed in the studio, but it does it effortlessly,” says Wood, who is using 42 inputs at 48 kHz on the Via Zammata tour and typically handles just over 50 with ZPZ. To enable Zappa to hear the “Rat Race” vocal effect in his in-ear mix, “We just loaded it onto a key, popped it into the monitor desk and—bang—there it was.”

Monitor engineer/production manager Pete Jones at the LVI. Photo: Steve Harvey

Other than the onboard Waves processing, says Wood, “I do use a TC Reverb 4000. I have the remote control software on my laptop so I don’t even have to look at the front panel. The only reason I’m using it is because over the 10 years I’ve been working with ZPZ I’ve created a bunch of reverbs for specific songs from Frank’s catalog. I will be able to reproduce those within the Waves plug-ins but it will take time to do that.”

At monitor world, Jones enjoys a similarly quick and easy setup. “If you can’t patch 16 XLR cables and plug in four things in 10 minutes then you’re not worth your weight,” he laughs. “If you can get hooked up really fast, then you have tons of time to work on the mix. That, combined with being able to do anything you want within this computer, is amazing.”

Jones generates eight in-ear mixes, one for each of the six musicians plus a guest mix, and one for himself, monitoring on headphones. The band is split 50/50 between Ultimate Ears and Jerry Harvey in-ear buds, he reports, using AKG wireless systems.

“Probably the greatest thing about the LV1 system is how fast it is,” he continues. “I’m able to take multiple orders from people onstage and then shoot it all in there. I’m mostly working on one screen; I have the other one for channel and rack stuff.”

As production manager, Jones is concerned about getting the most bang for the buck. The LV1 is not only an economical alternative to a traditional digital console, it also sounds good, he says. “This is the first system we’ve used where we aren’t giving up sound quality so that we can have an easy package to haul around the United States. Weight means money, so I’m saving on everything down to the gas for the tour bus.”

Plus, Jones notes, the equivalent outboard gear would require more crew. “When you have all those Waves plug-ins, it replaces racks and racks of gear. If we had racks of gear instead of all the plug-ins we’d have to have at least one audio assistant. The two touchscreens replace a console that would take us, with a Midas Heritage, a team of guys to tip. It would also take an equipment truck that costs a lot more than a little trailer that’s towed behind a tour bus.

“As the production manager, each one of those things is saving us money,” he adds. “Or, in essence, making the artist more money and maintaining the ability for us to have jobs, because he has to make money for us to have jobs. It’s a symbiotic relationship.”