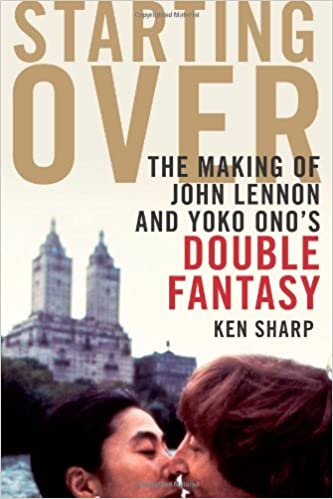

There’s been thousands of words written about John Lennon: Beatle or Songwriter or Musician or Activist or Wit, but there’s virtually nothing out there about his work as a Producer. The book Starting Over: The Making of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Double Fantasy captures all aspects of how the artist created what turned out to be his final statement, but in the process, author Ken Sharp provides a fascinating glimpse of how Lennon ran his sessions, got the sounds he wanted and cajoled those around him into giving their all.

There’s been thousands of words written about John Lennon: Beatle or Songwriter or Musician or Activist or Wit, but there’s virtually nothing out there about his work as a Producer. The book Starting Over: The Making of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Double Fantasy captures all aspects of how the artist created what turned out to be his final statement, but in the process, author Ken Sharp provides a fascinating glimpse of how Lennon ran his sessions, got the sounds he wanted and cajoled those around him into giving their all.

While he famously spent most of his time in the producer’s chair for Harry Nilsson’s Pussy Cats (1974) getting drunk and rowdy, it was an older, more mature Lennon who entered New York’s The Hit Factory in the Summer of 1980 to create Double Fantasy. The album, a musical conversation between himself and Yoko Ono, was co-produced between the pair and the legendary Jack Douglas, and during its creation, Lennon showed himself to be incisive as to what he wanted the album to sound like, clear as to how to achieve it, and surprisingly humble when it came time to solicit and weigh all opinions in the room.

United Archives ‘Lost’ Lennon Demos

Sharp’s book, an oral history with a cast of dozens intimately involved with the album, captures the interplay between the three producers, and their various production styles:

Andy Newmark (Drummer): Although he had not recorded for the five years prior to Double Fantasy, John demonstrated that he was still very comfortable and confident in a recording studio. Clearly, he knew his way around that environment. I was impressed right from the start with his authority, his clarity, and his ability to make decisions fast. He never lost his focus. That was fantastic. We got the leadership, confidence and authority that we needed. This was unlike many artists who I’ve worked for who are not leaders in this context, though they may well be amazing talents nonetheless.

George Small (Keyboards): There was one song where nothing was gelling, although I can’t remember the title of it. John took each of us aside and directed us individually. In about 10 or 15 minutes, he had everyone playing just what he wanted. He took the approach like he was fixing a machine or a watch and just tuned each one of us to the parts he wanted.

Jack Douglas (Producer): I knew instinctually how to make it work in the studio. My general philosophy about making records is sometimes you need to go in and write with the artist, like I did with Aerosmith. In other situations, you facilitate, from doing the budget to making sure the studio is booked to hiring all the musicians. Other times, you just have to gently guide the thing along. When you have a talent like John Lennon, do you need to get in his way? No. You just need to let it happen.

Lee DeCarlo (Engineer): Jack is a brilliant producer. John knew what he wanted and Jack helped him facilitate ideas. He was diplomatic. For example, if John had a nugget of an idea, Jack would go away for a day or two and he’d come back and say, “Remember that idea you had? Why don’t we try this?” Also if there was ever a disagreement, Jack was the tie-breaker.

Part of Lennon’s incisiveness in the studio came from the fact that he had labored over primitive demos for the songs that gave him a distinct picture of how the finished songs should sound, yet those demos also revealed both a certain insecurity and perfectionism:

Jack Douglas: He double-tracked because he hated the sound of his voice. And I used to tell him, “John, you don’t have to double.” These demos from Bermuda were recorded on a Panasonic boom box—it was just acoustic guitar on it, or in one case, piano on “Real Love” and him and Fred Seaman banging on pots and pans. He actually took the time to play those from one Panasonic to another one and double his vocal because he couldn’t bear that I would hear these things with a single vocal.

One anecdote regarding Lennon’s double-tracked vocals finds him in slightly pushy producer mode, yet there’s a hint of the famed mischievous young Beatle at work too:

Jon Smith (Assistant Engineer): One day, early in the project, as I was setting up in the studio, John and Yoko arrived early. Jack and Lee [DeCarlo] hadn’t arrived yet and John had an idea for a vocal part, a harmony part that he wanted to record. I loaded the multitrack tape and cued it up, but when we looked at the track sheet, there were no open tracks to put his part on. John said not to worry, there was an old trick they used to do on Beatle records. They would do an overdub on a track that already had something recorded on it, without erasing what was already there, but disconnecting the erase head from that track. The trick of it is to get the new recording at the right level so it’s balanced correctly with what’s already there, and we’d only get one shot at it so we’d have to get it right the first time. He told me he had faith in me and that he’d take full responsibility when Jack and Lee came. We decided to go right on to the lead vocal track that John had sung when cutting the song. He went out into the studio. We practiced it a few times to get the level right and then recorded it. When we played it back, it sounded great, and when Jack and Lee got there, we played it for them and they loved it.

Throughout the book, associates relay story after story of how Lennon’s analytical mind was always at work. More than once, people tell of complimenting him on a new track or perhaps noting that a certain Beatle song was their favorite, and Lennon never merely said “thanks;” instead he asked “Why do you think that?” in an effort to figure out what in his work resonated with others.

Over the course of Starting Over, Sharp skillfully takes the reader into the Hit Factory, observing the sessions like a fly on the wall. With plenty of period photos and copious insights from all involved, he serves up everything one could possibly want to know, from the name of the space-age guitar Lennon played through the sessions (a Sardonyx), to what his abandoned tracks recorded with Cheap Trick were like, to why Ahmet Ertegun was thrown out of the studio. While the narrative starts with Lennon and his cohorts attempting (in vain) to keep their recordings secret in case they flop, readers soon watch the ex-Beatle regain his confidence as the album begins to take shape. And if Lennon was experiencing doubts at the time, he didn’t allow his studio musicians to have any:

Tony Davilio (Arranger): I remember whenever Andy Newmark thought he made a mistake, he’d say “Uh-oh, they’re gonna get Russ Kunkel.” [Famed L.A. session drummer who worked with the likes of Bob Dylan, James Taylor, Crosby Stills And Nash, and Linda Ronstadt] He said it in a joking way. He must have said this about 50 times. After a few days of him saying this, John said, “G—dammit, Andy; if I wanted Russ Kunkel, I would’ve gotten him!” But in truth, Andy was the perfect drummer for the sessions.

From all the recollections in Starting Over, it’s clear that Lennon was a commanding presence, but also a man who created an upbeat, supportive vibe that encouraged everyone at hand to do their best.

Julie Last (Assistant Engineer): It was somewhat intimidating at first working with John. After all, he was a Beatle. But he was very easygoing and funny and so excited to be back in the studio after five years of being a “house husband.” His spirit was like a little kid in a candy shop. You just got swept up in his joy at being back to making a record again.”