My Dad had an unbelievable memory and depth of knowledge of Hollywood’s Golden Age of film (generally considered the period spanning the mid-1920s to the early 1960s). If we were flipping through channels and came across an old black-and-white movie, he could watch it for about 15 or 20 seconds, then tell you the title, the year it was made, who starred and what (if any) Academy Awards were given to the film, actors or actresses. He’d usually be able to name the director and tell you if the film marked the debut of a soon-to-be prominent actor or actress. It never ceased to amaze me.

Occasionally, I’d get stories of how my Dad and his cousins would pack lunch and head for a movie theater on a Saturday morning, spending the entire day soaking up double-features, newsreels, and cartoons—one of their few means of escaping the Depression and getting a glimpse of the rich and famous. He explained to me how actors and actresses of the time were signed to specific film studios, and I was surprised to learn that they weren’t allowed to seek work outside of their contracted studios, much like modern-day recording artists sign exclusively to a particular record label.

Dad had his favorites, some of whom I recognized: Bette Davis, Cary Grant, Katherine Hepburn, Clark Gable, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers. One of his top all-time favorites was Hedy Lamarr, an actress with whom I was unfamiliar and whose name I found most unusual.

Mix Live Blog: By the Students, For the Students

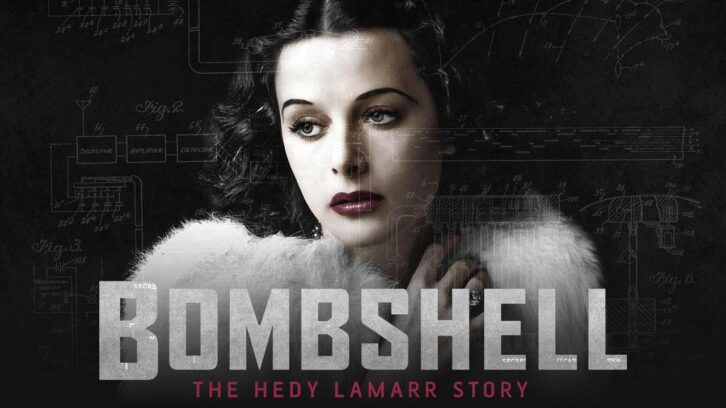

Fast-forward to a few weeks ago. I was flipping through TV stations and came across an episode of PBS American Masters called Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Produced in 2017, “Bombshell” tells the story of this beautiful Austrian-born, er, bombshell actress. I could see why Lamarr was in my Dad’s top ten. I tuned in about halfway through and decided to watch for a while.

The film documents some of the usual Hollywood stuff—the rise and fall, struggles and triumphs of a star—but the episode took a compelling turn when the discussion shifted to Lamarr’s accomplishments as an inventor. “Interesting,” I thought. My Dad would always tease me if we’d see a beautiful Hollywood actress in an interview or TV appearance. He’d give me a smirk and say, “She’s really quite intelligent,” knowing fully well when a glamourous icon was there strictly as wallpaper. Maybe he was teasing me from the beyond.

Lamarr had quite a loyalty to the United States and was concerned with the way World War II was progressing. During the Summer of 1940, she learned that a British ship with 293 people (including 83 children) had been torpedoed by a German U-boat; there were no survivors. According to Bombshell, Lamarr felt guilty that she was in Hollywood earning a fat living while the Allies were losing the war—and U-boats gave the Germans quite an edge. A torpedo launched at a U-boat might need to be redirected, but it was easy for the Germans to find the frequency used for communication between the ship and the torpedo, and jam it by creating interference on that frequency. Lamarr decided to tap into her inventing hobby and do something about it.

The actress came up with the concept of constantly changing the communication frequency between the transmitter and receiver while maintaining sync between the two. This was a technology that would make it much more difficult for an adversary to jam the control signal, because a huge amount of power would be required to block all possible frequencies. As explained in Bombshell, this is called “frequency hopping.”

That’s when I fell off the couch.

You mean to tell me that this bombshell invented frequency-hopping spread spectrum (A.K.A. FHSS)—the same technology used in just about every wireless microphone, instrument transmitter and in-ear monitor system that we use today? In 1941??!!

Yep, and that technology is also used for securing military communications, communications to/from POTUS, and cellular transmission.

The tricky part for Lamarr was synchronizing these frequency hops between the transmitter and the receiver. This is where she called upon her friend, avant-garde composer George Antheil. Antheil had previously composed a piece of music that employed 16 player pianos running in sync.

What if they used the synchronization aspects of the piano rolls to cause the radios guiding the communications to change frequencies?

It sounds insane, but the same technique that kept the player pianos in sync was used to keep the radio transmitter and receiver in sync. Marks on player piano rolls set each device to a particular frequency. As long as the piano rolls played at the same speed, the ship and the torpedo could hop from frequency to frequency while maintaining sync. Absolutely brilliant.

When the concept was brought to the US Navy, they did in fact think that Lamarr and Antheil were insane. They poo-pooed the idea and it took another 20 years before Navy ships adopted frequency-hopping technology. It wasn’t until May 1990 when an article published in Forbes revealed that Lamarr’s contributions to communications were as significant as her good looks.

The frequency-hopping techniques established by Lamarr and Antheil are useful for maintaining security in any location where a large number of radio communications take place in a confined area. Sound familiar? Everywhere, every day. This technology makes it possible for us to use our wireless production gear, WIFI and cell phones, all thanks to the Bombshell. Lamarr received a patent for her idea, but she never received any royalties.