About a year ago, I was rummaging through a neighbor’s trash—well, not exactly. I was digging through a garage sale, and like they say, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure…but what I was finding was trash. As I left, I looked in one last cardboard box on the driveway, and from under all the broken toys and stray playing cards, I pulled out a relic from another age: a consumer MiniDisc of Natalie Cole’s 1991 smash, Unforgettable with Love.

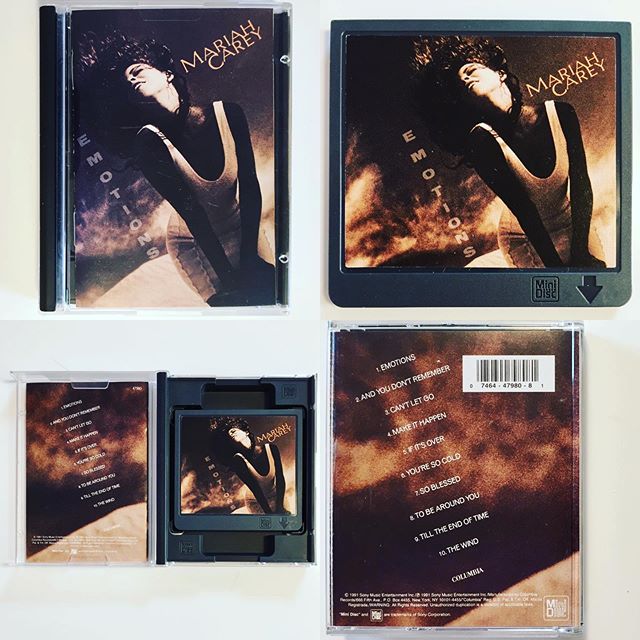

Finding a forgotten format is always a little intriguing, and my interest was piqued. The MiniDisc—a magneto-optical disc housed in a cartridge similar to a 3.5-inch computer floppy—was introduced by Sony in November 1992 to great fanfare. The company touted it as the successor to the compact disc, because consumers could record to it like an audio cassette, but they’d get the audio quality of a CD. In truth, the quality wasn’t even close, as it used a lossy data compression scheme called ATRAC (Adaptive TRansform Acoustic Coding) that Sony developed in order to cram 74 minutes of audio on the diminutive disc. They even updated it four times over the years, raising the recording time to 80 minutes and getting ever closer to CD quality, but it never quite got there.

Ultimately it didn’t matter, because in the U.S., no one was listening anyway. The relative handful of commercial MiniDiscs that were released here cost $5 more than CDs, and Sony’s Walkman MiniDisc players ran more than $500 (about $875 today). Adding to the hurdles facing MiniDisc, it wound up going head-to-head against Digital Compact Cassette, another format released around the same time by Sony’s rivals, Philips and Matsushita. Confused about which overpriced, underwhelming format with little in the way of catalog releases to buy, consumers opted to go with neither and stuck with their trusty analog cassettes until Apple’s iPod banished C90s to attics everywhere around the turn of the millennium.

While DCC died a quiet death in 1996, MiniDiscs caught on with consumers in Japan and enjoyed some success in Europe and South America; in the United States, the format even carved out a niche for itself with radio stations, studios, home recordists and news reporters, and Sony milked that for all it could, reportedly selling 22 million recorders worldwide by the time it pulled the plug on MiniDisc hardware in 2011.

Given that the MiniDisc flopped with U.S. consumers, however, commercial releases like the Natalie Cole album I unearthed vanished from stores in the blink of an eye, so it was hard (or perhaps very easy) to believe I’d found one at a garage sale. I dug a little deeper in the cardboard box and soon I’d found a dozen releases. Nearly all of them were on Sony Music labels and I’ll bet they were a “12 MiniDiscs for 1¢” deal from Columbia House. Naturally, there was no player to be found among the junk and I’ve never owned one, but despite that, for reasons unknown to even myself, I bought the dozen for $2.

A month later, I came to my senses, realized this was yet more clutter I’d introduced to my home office and promptly put them up for sale on the online music collecting site Discogs. Since then, I’ve sent Simon & Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits to Chile, Michael Jackson’s Bad to Poland, and other discs elsewhere, but always to other countries…until last month.

A woman purchased the MiniDisc of Mariah Carey’s debut album, Emotions, and wanted it fast, so could I UPS it overnight to New York City? Sure. Then I saw her mailing address: 25 Madison Avenue—Sony’s U.S. headquarters. This couldn’t be a personal purchase. At that point, I had to ask—since Sony owns Columbia Records, wouldn’t they have Carey’s MiniDisc in a closet somewhere? It turned out they needed it for a corporate display illustrating 40 years of the Walkman, and it was easier to buy one on Discogs than find one internally. Fair enough. I mailed it off, but not before polishing up its plastic case for them. One man’s trash is Sony’s treasure, apparently, and somewhere that relic of a dead format I picked up for 17¢ is now a museum piece, having fittingly returned from whence it came.