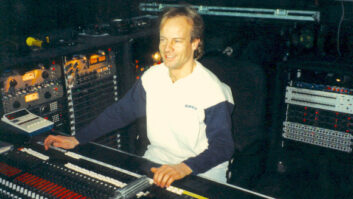

Chanhassen, MN (April 28, 2016)—While the world still reels from last Thursday’s passing of enigmatic superstar Prince, mainstream press outlets and social media platforms have become rich with memories and recollections of his work, personality and unique imprint on the music industry. Among those is audio engineer Robert “Cubby” Colby, who extensively worked with Prince during what could be considered the height of his Purple reign: 1980 through 1988 as monitor mixer and front-of-house engineer on tour and audio tech/music mixer in the studio, at the artist’s own Paisley Park Studios outside of Minneapolis. Having served his technical needs in a wide range of faculties, there are very few professional engineers having had as many interesting moments with Prince as Cubby.

Here, Pro Sound News Editor-At-Large Steve Harvey shares a Monday afternoon conversation with Colby solely on the subject of Prince Rogers Nelson. This followed a reunion for many of Prince’s former band mates and musical collaborators, among others, who gathered in Minnesota on Sunday evening.

“I did many after-hours shows, but mainly I’m very proud of the six tours I did with him,” Colby begins. “[I] started and completed them all, and all of the rehearsals. I was originally from Minnesota and then I moved to Chicago when I took the gig with dB Sound. [Colby worked at dB Sound as audio tech and monitor mixer on tour with Heart and Kansas from 1977 until 1980, where he began his stint with Prince for the Controversy Tour 1980/81—Ed.] Then Prince moved me back to Minnesota—but he never believed I was originally from there. He also joked with me about that. ‘You’re from Chicago, right?’ ‘For the tenth time, I’m from Mankato, Minnesota.’”

“He was a very, very playful, passionate person. That’s how I got to know him. I’ve done a couple of Minnesota phone-in interviews [since Prince’s passing]. So many questions get asked in terms of what it was like mixing for him. It was the playing field where I really feel like I grew up. I learned more from him than I could have learned from any textbook. That goes beyond musical experiences. He was a very good engineer in the studio. He knew his equipment, and what he didn’t know he would learn.”

“Last night Wendy [Melvoin] and Lisa [Coleman, members of the Revolution, 1980-1987] talked about our 12-hour rehearsal days. They always got a chance to take maybe two half-hour or one-hour breaks during that time. I never was able to leave the room—because, when they left, he stayed to work on mainly guitar stuff, pedal board stuff. He’d take the pedal board and plug it into the Linn drum machine. It was always evolving, so you did whatever you could to stay ahead of the curve. It was a great experience in every way.”

“For Controversy in 1980, there was no money. I was kind of the go-to guy back then. It was all his equipment, which came out of the basement of the house that went into the auto body shop that we rented out, and then eventually [we] turned it into a rehearsal studio. Little by little, we added curtains and carpet, then after Controversy we put that set in to be our little stage. He had his pedal board and mic stand five feet in front of the Soundcraft 400 console [where I sat]. He looked at me and I looked at him, six days a week. It was awesome.”

“I look back and think, my god—what he had to tolerate. Even though much of his time was conducting the band and doing things, once we got into rehearsal it was always one-on-one, it was great, just phenomenal.”

“Six tours in nine years with Prince was a long run. I was there as long as the Revolution was there, and that was his longest-lived band. I saw everybody last night; it was absolutely phenomenal: Wendy and Lisa, Brown Mark, Matt Fink, Bobby Z, Susan Rogers flew in from Boston, Sheila E., a couple of the backline guys, and security and old management. Everybody spoke; I’m sure it was very emotional for the Revolution, as they met prior to coming into the room. Dez [Dickerson] couldn’t be there, [nor could] LeRoy Bennett, who did all of the incredible lighting work during that period. It was great to see everybody and reminisce. The stories were endless. The room was full of tears and laughter, all at the same time. His sister, Tyka [Nelson], showed up near the end and thanked us all. He has a half-brother, Omar [Baker], who spoke to us as well.”

PSN: Paisley Park was built in 1985?

“It was right after Purple Rain. What is in Studio B now was in his home. I was there for all of that install. He put in a custom-built API, completely discrete and built for his height, his reach. It took over a year. I did all the internal work; I used to have a key to the house and would drive down to the back and let myself in, getting there before the techs showed up. I worked through the holidays to get it done. While that was being done, he was in Los Angeles, and by the time we got the studio done in the home, Paisley Park Studios was almost complete. They had built A, which has the big SSL in it, and C, which had a Soundcraft console and was mainly the band rehearsal room. Then after we rehearsed and learned everything, we moved into the big production stage, which was big enough to drive a semi into and turn it around. It’s a phenomenal facility.”

“Back then, 10 o’clock in the morning the doors would open and the FedEx guy would roll in a cart, and the band would gather around the coffee pot and the purple dove was in the corner. The guy would show up every Thursday to clean the cage. It was unbelievable.”

“Then, upstairs, across from the offices, was the wardrobe department. There were eight girls in there, four professional sewing tables; everything was made there. Except the shoes. And that means for all the band. Every tour, the band was taken up there for fittings. The only person who was ever [dressed] the same was [Matt] Doctor Fink. He told the greatest stories last night. He’s such a character.”

“It never felt like I was going to work. It was as if I was going to Paisley Park. I just had to be there an hour ahead of schedule, get everything turned on, everything ready and make sure everything was ready for the rest of the band. As long as you did what you were asked to do, you were focused and you had your notebook and a pen … because there was no way I could remember everything that he would ask me to do and remind him to do later. Or make notes on changes, to remind other band members, etc.”

“Prior to Paisley Park it was such an intimate group. We were in an industrial park so we had to set hours. It wasn’t until he got his own playground—and I always refer to it as ‘his playground’ because he could walk out of rehearsal, four feet across the carpet into Studio B or eight feet to Studio A. I can tell you exactly how many paces it took to go from here to there. The saving grace for us was that we couldn’t make noise after 7 o’clock at night. But until the playground was built, [it was small]; then he had to have three different studio engineers staffed every day to keep up with him.”

PSN: Was it a help or a hindrance that he knew engineering?

“It helped me. I learned more [that way]. His technique was that everything had to be in the red. There was no gain structure. There was something [special] about his ear; he liked to saturate either discrete electronics or op amps to get that harmonic distortion. That’s disappeared; now everything is so clean. You would work ways to get a pure path and it always seemed like he had ways of having a little bit of dirtiness. That was more of a recording approach that he had learned over the years. If he did that out front I would explain, ‘this isn’t good, look at the faders at -30 and it’s spitting blood out of the VU meters.’ ‘So?’ He learned over the course of time.”

“I said to somebody today, there were months that would go by, [all that was said was] ‘Hello, how are you?’ He wouldn’t bring up the mix at all. Sometimes they’d send a security guy out: ‘Prince wants me to give you this $100; he thought the show tapes sounded great.’ Months would go by that you wouldn’t talk to him. No news was good news. But he was always very polite, very cordial. We had a very good trust, with each other. If he asked me if I was ready and I wasn’t I would say, ‘No, I’m not ready. We’re not ready.’ And he respected that. So many people got burned along the way for saying, ‘We’re ready to go,’ and they weren’t ready. Five minutes could make a big difference.”

“When I got the phone call on Thursday morning following Prince’s passing], I didn’t believe it at first. I had just sent an email to Kirk Johnson [Prince’s longtime friend and drummer] the Friday before, when I heard about the plane landing in Moline. I told him, I hope he’s feeling better, I’m going to be back in 10 days; let’s get together. I don’t live far from Paisley Park; I live in Chanhassen. I moved to this home about four years ago. Prior to that I was about eight miles away. It was radio silence, which didn’t surprise me. It happened. There was no need for an explanation; it was just the way things were.”

PSN: Were you involved with the Purple Rain show at the First Avenue club in Minneapolis?

“No, I had nothing to do with the soundtrack. That happened prior to the tour. Once they geared up for rehearsals, that’s when I was brought back in. I wasn’t asked to move to Minnesota until after Purple Rain. That’s when I started at front of house; prior to Sign o’ the Times I was his monitor guy. I did monitors on Controversy, 1999 and Purple Rain. But when you were doing rehearsals for him during that time, at the old studio, the front of house was basically side fills turned in at the band. That was the left and right mix. Then wedges for everybody else. He never had wedges. He relied on the side fills. So you were doing both jobs at that time.”

“He had a really good backline tech back then, Don Batts. When Prince had the Revolution it was he and Don. Prince had learned all this engineering technique and learned a lot from Don and [other] recording engineers. He was very young then. I think everything I learned from him was beneficial. I think he learned from all of us. Whether he wanted to admit it or not, he would learn along the way. Especially on the electronics side and console side.”

“He never did embrace digital consoles. Ever. The API was his favorite console to work on. Now that everything has gone to digital and Pro Tools and saving files that way, I think he realized that some people cut out more. He would throw the fader up, EQ stuff, put compression on it, do all the effects, but he wasn’t the kind of guy who would sit at the patchbay and do the routing. He would tell the engineer, ‘I want this to go there.’”

PSN: He worked a lot at Sunset Sound in LA. Was that because of the API with DeMidio mods?

“He often referred to that. During the Paisley Park build, many of those people were involved and came into the control rooms to give their input to the builders. There were Westlake Audio studio monitors in all the rooms—remember those, with the big black walnut horns? Just beautiful. The studios are still very much intact. The production stage is sub-divided: one side is a rehearsal studio, and the other side is a clubby playground with basketball hoops and stuff like that.”

“There was always a basketball hoop within 10 feet of the front door, at all of the different Paisley Parks. His favorite thing during rehearsals back then was, he’d tell the band to stop on the one—the old James Brown thing—and he’d say on the microphone, right in the middle of the afternoon, usually on a Friday, ‘Who wants to play basketball?’ The music would stop, everybody would put their hand up, and he’d disappear into another room and come back with basketball shoes on. Once you were outside, all bets were off. He was rough. He would push—‘that’s all you’ve got, Rob Colby?’ You gave it to him and he took it and still outplayed everybody, always. We’d go back in, he’d come out a half-hour later, all fresh, maybe in a new suit, we’d run the set one more time. If he was going somewhere he’d say, ‘See you Monday.’ Otherwise, he’d say, ‘See you tomorrow at 10.’”

“In the very early days he’d wear a pair of Levis. But the guy always looked like a million bucks. I said to him one day, Prince, you look like a million bucks. He says, ‘That’s all? It’s more like four million when I look at myself.’ I’d say, ‘okay man, you look like five million.’ He goes, ‘I think that’s more like it.’ He was always asking me if I had a rope for a belt … there was a lot of banter, back and forth. It was a lot of fun.”

“I used to mix a lot of his different bands [at First Avenue]. Moving from monitors to front-of-house, he’d stand out there next to me. I’d do the soundcheck and he’d show up for the show and stand there. I looked like a mad scientist with fuzzy, curly hair with a receding hairline. He would hang, and after the show I’d go to the dressing room and he would talk so nicely to the band. I’d walk in the room and all the eyes would turn, and he would never say anything to me. But I knew he had something good to say. You’d get the look or a nod. This was [for] The Time and all the different bands he had come through Paisley. And he’d get up and play with them, of course. But he loved hanging at the console. That’s where he felt most comfortable. He didn’t want to be in the VIP booth.”

“Controversy was an outstanding time period. [He already had] that Minnesota funk sound going. The first time I spent time with him, he came in late after I set up the entire PA. Everybody else had left the building, and he walked in. He had said he’d like to play the instruments onstage, so it was him and me. He sat at the Linn drum machine and programmed a beat. I bought that up in the drum wedge. He turned around at the Simmons electronic drum set, with a real snare, hat and cymbals, and started playing to the Linn drum machine. We dialed that in. Then he walked over to the keyboard. I sent the Linn drum machine over there, and he talked into the microphone to me, played the keyboards, then went to Lisa’s keyboard position and did the same thing. I tried to stay ahead of him as he went from one mix to another. He put the bass on and jumped down. Prior to him playing the bass he’d been playing bass lines with his left hand and playing horn punches and swells and pads with his right hand. I thought, ‘look at this guy go.’ Three-handed music, but there’s only two hands on the guy. Then he put the guitar on, and he had a moving keyboard that he rolled out. I dialed that in. He was playing keyboard bass lines with his right hand and playing lead lines with the other hand on his guitar neck, his Hohner guitar. That is the greatest-sounding clean guitar that I’ve heard, until this day, 40 years later. We started at 11 o’clock at night. We got done and I looked at my wristwatch: it was about 3:30 in the morning, and it felt like it had been 15 minutes. Unbelievable. This was my first day. I was ready to go home at 11 o’clock. I didn’t know who he was, but it didn’t take long to figure it out: this guy is unbelievable.”

“Check out his Batman performances. That was after the Revolution with the drummer Michael Bland. Even though I love Bobby Z, he’s nothing like Michael Bland. That Batman band, with Miko Weaver [guitarist], Levi Seacer, Jr. [guitarist], Rosie [Gaines, vocalist], Prince, [Brown] Mark [bassist] and Michael [Bland], that’s where his guitar playing, in my opinion, was just out of this world. He played with all those Boss pedals. He had the same pedalboard for 20 or 30 years. He’d take the red one out and put a yellow one in. That’s the stuff he’d do during the one-hour pee break for the band that I never got. He’d take the thing out of the box, didn’t look at any paperwork, plug it in and play with the knobs … the countless hours of listening to him play. It was just phenomenal.”

“We would average six or seven 90-minute cassettes every rehearsal day. Imagine the stuff that’s in the vault. Saturday afternoons, it would be just him and me and Sheila in there. He’d ask me what I was doing. It was never, ‘Hi, how are you?’ The phone would ring, I’d pick it up and say hello. ‘Can you be here at noon?’ ‘Sure.’ Or, ‘sorry, no, I can’t.’ And noon meant I had to be there an hour ahead of time. The teapot would be on, plenty of honey. It was a Styrofoam cup, half a cup of honey and a little bit of tea on top, and some milk. You’d get that going, turn everything on. I never picked up a guitar and tuned it; he’d do all that. He’d play keyboards or drums. He’d get somebody that played guitar and he’d play drums. Somebody would knock on the door and it would be some sax player he’d invited over.”

“Eric Leeds and his brother Alan were there last night. Alan was tour manager. He told a great story about body bags and French passport control. Bernstein and Rock-It Cargo saved the day and took everything. There’s no reason for one guy to have ten body bags full of clothes. They took the clothes out, looked at everybody and said, ‘Who wears this?’”

“I think Matt Fink’s story last night about the bullhorn on the airplane is the greatest story I’ve heard. This was on the Dirty Minds tour. Prince told Matt Fink to pull the bullhorn out of the safety equipment [in the overhead bin]. He said it would be great to have a bullhorn in the show: ‘Go up and grab that.’ Matt got the bullhorn and Prince said, ‘Put it in your bag.’ ‘I don’t have any room in my bag.’ He walked down the aisle and gave it to Dez Dickerson, and he put it in his bag. They landed and the pilot came out and said, ‘You, you and you and your group, you need to wait.’ Everybody got off the plane and they got arrested and taken downtown to Memphis. They were handcuffed; it was a Federal offense. They were in the holding tank and a lady looked through the window and says, ‘Is that you, Prince?’ They all think, thank god, somebody recognizes him. ‘What are you doing in there?’ He says, ‘Can you help us?’ He’s trying to explain why they’re there. At the end of the day all she wanted was an autograph. As soon as they signed the piece of paper they were free to go. That’s the kind of a jokester he was. This kind of thing had been going on a long time.”

“I’d bring a PayDay candy bar [to Paisley Park], thinking if I didn’t get a chance to eat in one of these breaks again, like everybody else, I’d better have something. I used to sit the PayDay on the meter bridge of the Soundcraft in the middle of winter so it would thaw. He would put his car keys right next to it; we were five feet apart for 60 hours a week, every day, back then. One day I got up and did something, and came back and when it came time to be hungry I looked up and the frickin’ candy bar was gone. I’m looking around, and he’s looking at me, and he’s eating my candy bar. I said, ‘my PayDay.’ He said, ‘No, that ain’t til Friday.’”

“So every day from that day on I would buy two PayDay candy bars and I would always leave one out there. When we were done with rehearsals it was my duty to put the cassettes in the car and start the car. When he said, ‘Start the car,’ that meant we were done in five minutes, but only in the winter when it was cold. It was a little business strip mall, with a Ziebart at one end and a paint shop at the other end, with us in the middle. We must have been good tenants. We weren’t out there smoking cigarettes or hanging out. It was all business. So I’d put the six or seven cassettes in the car and I’d find all the PayDay wrappers. He had a sweet tooth, that’s for sure.”

“It never felt like going to work. It was always something I looked forward to. Obviously the days were long. But he took such great care of himself. You can’t do the hours that he did … there was no nonsense going on.”

PSN: He was a vegan?

“I think that had a lot to do with him becoming a Jehovah’s Witness. Then the pain and all of that … so many things are coming out; I don’t believe any of it. I think it was the result of no medication, no medicine. He was such a believer that he became a vegan to cure himself. I know close friends [and] that worked for them, when chemo didn’t. He was a really slight guy. Robbie—the guy that used to go ahead to the hotels in every city—he’d get there the day before and get the hotel rooms set up; I never knew Prince carried weights around with him. He was always very fit.

PSN: For the Purple Rain recording, I read that he enlisted help from the Minnesota Ballet.

“He asked for them to come in and help. They [the band] put so much time and effort into it. It was passionate. You can’t use the word perfectionist. He always said, ‘nothing is perfect.’ We can only strive to be as good as we can be. ‘Whatever you do, don’t do the same mistake once,’ he’d say. I think that’s a famous jazz quote. He used it many times. And fair enough. He never cut corners with his live performance. That was what he really, really worked so hard at. In the studio he would cut corners on quality in order for everybody else to keep up with how much stuff he was writing at the time. They estimate there’s over 1,200 unreleased songs in the vault. That’s an album of 12 songs every year for 100 years.

PSN: Now there are questions about ownership …

“That’s more concerning [to] the people that are close to that. Not close to him, but close to the studios and the vault. Our tech room downstairs, which was basically a music store by the time I left, was right there; you took the elevator down and it was the vault on one side and the door into the tech room on the other. It’s going to be a huge job to go through it. Let’s hope the right people get involved to keep all this going.”

“It was just such an honor to be able to work with him and have the time that I did spend with him, and learn so much. At the end, we were friends. I’d see him around town. He was so polite, such a good person. Outside of being a great musician he was a great guy.”