Georgetown, CT (May 1, 2023)—It’s a bright April afternoon in Georgetown, Connecticut as I pull up outside the old stone church. The parking lot is empty except for a white van, out of which hops Anthony Coscia, an amiable guy in a gray fleece vest and matching Grateful Dead “Stealie” ballcap. “Got a jacket with you?” he says. I nod. “You’ll want to put it on; it gets pretty cold in there.” The former church has no heat—or running water, as evidenced by the portable toilet outside—but it does have what some Dead fans consider to be The Holy Grail.

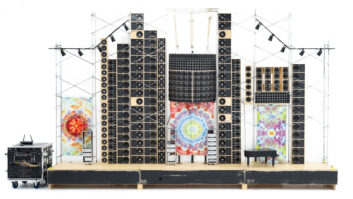

He leads me into the gloomy, dank edifice; we turn the corner into the main room, and there it stands at the back: “Le Petit Mur De Son“—Coscia’s soaring, 30-foot-tall, half-scale replica of the Grateful Dead’s legendary Wall of Sound.

AUDIO EXCESS

The original Wall of Sound P.A. was a successful failure that became the stuff of legend among Deadheads. A colossal system that was something of a precursor to the modern line array, it was envisioned in 1972 by audio engineer/prolific LSD chemist Owsley “Bear” Stanley and created with Dan Healy, Mark Rizene, Ron Wickersham, Rick Turner and John Curl. As the name suggests, it was an actual physical wall of speakers—a collection of six separate P.A.s, ground-stacked within scaffolding and placed onstage behind the band to act as a simultaneous house and monitor system. The instruments had their own dedicated speaker columns within the wall, which resulted in low intermodulation distortion and inadvertently provided on-stage localization, because each performer naturally stood in front of his own column to hear himself.

A total of 11 channels fed the system: vocals, guitar, lead guitar, piano, three drum channels, and four bass channels—one for each string, separated by a quadraphonic encoder. Vocals were summed to a mono channel, and the issues of vocal mic feedback and stage bleed were solved by placing two out-of-phase condenser mics at each mic position; one was sung into while the other captured stage ambiance, so summing them together canceled out everything but the vocal.

The Grateful Dead’s final version of the system, standing roughly 98 feet across and 36 feet high, traveled in four semis and required 21 people and an entire day to load-in. A total of 586 JBL 15-, 12- and 5-inch speakers and 54 Electro-Voice tweeters were housed in Hard Trucker-style birch plywood cabinets, all powered by 48 McIntosh MC-2300 amplifiers for a total of 28,800 watts.

The system’s sheer bulk was part of its charm—and ultimately also why the Wall came down for good. The band first tried to perform through a preliminary version in February, 1973, and blew out every tweeter during the first song. Undeterred, the Dead began touring with the prodigious P.A. in March, 1974, only to retire it seven months later when production costs exploded due to a nationwide gas crisis. Nonetheless, the Wall of Sound was preserved for eternity when the band filmed five shows with it at San Francisco’s Winterland in October, 1974; that concert footage became the heart of 1977’s The Grateful Dead Movie.

LIVING THE DREAM

Anthony Coscia never heard the original Wall of Sound (he was six years old at the time), but that hasn’t stopped the lifelong Dead fan from building his own. The resulting behemoth towers above us as we sit on folding chairs next to a propane cannon heater blasting away in the dim, freezing church. We’ll wind up talking for more than an hour before he fires up the Wall.

For most Dead fans, rebuilding the legendary P.A. would be a fun, idle daydream at best, so what would make someone decide to start “living the dream” and actually build it, sinking hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars into the project?

Well, the first thing to know is that Coscia has built a few Walls now, and while that might sound like a hobby that’s spiraled out of control, it’s anything but. Much like a Dead show, the fun is in the journey, but at its heart, it’s still a money-making venture. Coscia’s background makes him uniquely qualified to rebuild the Wall, too—having previously worked in construction, he had a solid understanding of how to build it, and as a luthier catering to the Grateful Dead musician community, he’s tapped into a network of often well-heeled, well-connected Deadheads that might be willing to give the system a new home.

“The last five years, I’ve been exclusively making guitars, moving from a hobby perspective to a professional, full-time thing,” says Coscia. “They’re specific to the Grateful Dead universe; I don’t make clones, but I know my musicians and what they need, and I make Hard Trucker-style speaker cabinets for them as well. It got to the point where I’d have 20 or 30 full-size cabinets in the shop, so it became, ‘Why don’t I just keep going and make the Wall of Sound?’ When I did the first Wall, it was tiny—five feet tall, eight feet wide. The most expensive speaker was $2 and the cheapest was 28 cents. My total budget was probably $1,000.”

That first Wall, a 1/6-scale working replica with speakers ranging from 2.5-inches down to 7/8-inch models used in cell phones, made the front page of The Wall Street Journal in 2020. The notoriety led to building three 1⁄4-scale versions, each standing 14-by-10-feet—one for Coscia to show at events; one for a client; and one which was donated to HeadCount, a voter-registration nonprofit that sold it for $100,000.

Buoyed by their success, Coscia began to think big—or at least bigger—and started building his half-scale Wall of Sound, in part because the 1/4-scale systems could only provide a hint of what the original sounded like.

“At the end of this half-scale, I’ll know whether the whole thing really has merit,” he says. “A million people tell me ‘The best concert I ever saw was a Wall of Sound show,’ but I don’t believe they were in a position to really know. Either A, they were dosed at a Dead show, or B, they were impressed by what it looks like, and it’s hard to have an opinion based on anything real if you’re busy going ‘Wow.’”

THE WALL OF SOUND’S SOUND

Coscia starts the system, and soon the church is filled with the melodic strains of Grateful Dead tribute act Half Step as a multi-track of the band plays through the Wall. The localization works like a charm, giving something of an immersive effect near each instrument’s column. Meanwhile, across the room at the altar, the various systems congeal cleanly to become a pleasing full band mix. Half Step on a half-scale Wall doesn’t sound half bad, it turns out.

So are the rumors true and the Wall of Sound was actually the greatest concert system ever made? No—but you can see why it probably was in 1974.

Surprisingly, Coscia agrees with that sentiment, and it may be why he wants his multi-ton nostalgia machine to be visually identical to the original, but not beholden to the technology that comprised it. Rather than use two out-of-phase mics to prevent mic bleed, he employs Optogate infrared microphone gates plugged on to the ends of the vocal mics. Rather than slavishly follow the original console-less signal paths of instrument-preamp-amplifier-speakers, all signals go to a Midas M32 virtual digital mixer along the way so that he can reassign speaker columns without having to rewire everything. Rather than worry about amplifier speaker loads, he uses passive Zero-Ohm Multispeaker System units to power a given column in parallel off a single amplifier without using transformers. If he had the time, knowledge and an unlimited budget, he’d jump at the chance to incorporate DSP and beam-steering to further improve the sound.

In short, Coscia has no problem employing modern-day pro-audio advances to make his Wall more flexible, easier to use, likely better sounding and definitely more marketable to a potential buyer.

Dead & Company: Keeping It Live

However, while recreating a 1970s sound system, Coscia faced a very 2020s problem: supply chain issues. Finding parts, technology and speakers was a challenge in the wake of the pandemic, and many manufacturers were unable to ship product. Ultimately, he went with CVR Audio amplifiers, while his eight-inch speakers were produced by Spanish manufacturer Beyma, and the three- and six-inch speakers were Italian-made FaitalPro models.

When all those speakers were put in cabinets, they had to be modified—not to affect sound quality, but to ensure they resembled the ones in the Dead’s Wall. Some baffles were sponge-painted to look like the cork used on the original’s JBL speakers, while a few dust caps were painted silver to replicate aluminum. The original speakers had front-facing clips so that they could be yanked out and replaced mid-show if needed; Coscia ordered 1,200 custom-made clips to put on his cabinets purely for the aesthetics, but with only 200 delivered so far, he hasn’t installed them yet.

That’s fine, as he faces a far greater challenge at the moment. To borrow a Grateful Dead phrase that seems particularly appropriate given our surroundings, Anthony Coscia is looking for a miracle.

UP AGAINST THE WALL

The half-scale Wall temporarily moved into the church last fall thanks to a Dead fan who had just bought the building. It was a lucky break for Coscia, who needed the room to properly assemble and fine-tune the system. However, that time of largess is coming to an end: The Wall of Sound has to move out by mid-May so that the building can be renovated to house a music charity, Spread Music Now.

“It will kill me if I have to put the Wall into storage,” says Coscia, not because of the effort or cost, but because the Wall will be harder to sell if it can’t be seen and heard.

If he can’t sell it in time, Coscia’s hoping to find a local venue to partner with—one big enough to keep the Wall on its stage and give visiting bands the option to use it or the house system. “I’m willing to split revenues or whatever; we’ll make it work for everybody,” he says, adding that he gets emails daily from bands asking to play through it and Deadheads who want to hear it.

Coscia is confident he can beat the clock and get the half-scale Wall out of his hair one way or another. He needs to, in order to vacate the church, avoid renting storage lockers, recoup thousands invested in the project, and much more, but there is one reason above all why he needs to do it—a reason that looms as large as the massive sound system itself: The funds will help him build a final, full-scale Wall of Sound in time for 2024—the system’s 50th anniversary.