This past summer, after 18 years of building, rebuilding, recording, inventing and producing in his largely private Barefoot Recording, nee the legendary Crystal Industries Recording in Hollywood, producer Eric Valentine is turning over day-to-day operations to a few close friends and opening the rooms and the gear to all who want to record quality music. And he’s on the cover of Mix, for all the right reasons.

The arc of the Eric Valentine story, from scrappy Bay Area boy drummer to big-time L.A. rock producer, is practically script-ready, at least on the surface.

In the first act, there are makeshift studios patched together with foam and blankets in garages and spare rooms, a teenager with a Portastudio and friends in multiple bands. Dad is an aerospace engineer, mom loves music. It’s the 1990s, the first wave of tech meets music, and the local music scene is hot. The Bay Area is bumping!

The second act starts in Redwood City, Calif., south of San Francisco, with unknown-but-soon-to-be-huge rock bands visiting our main character’s hole-in-the-wall studio, back to back, and instant success! In his 20s! Label advances, new gear, the money flows like wine! There’s a move to Hollywood and the purchase of a Big Famous Studio, one with a rock and roll history and a musician’s soul.

The third act opens with crazy energy, the new kid in town tinkering and experimenting, buying up guitars, drums and amps! A real studio, all his own, no distractions! Then, the perfectionist inside decides he’s not satisfied, so he builds his own console and forms an electronics company on the side. Eighteen years go by. The left brain and right brain merge, in harmony. All this while spending more than half his life barefoot, literally.

Related: The Class of 2018, by Barbara Schultz, June 1, 2018

In the finale, the studio opens up to the world. Our lead actor builds an amazing musical playground at home and embraces a new creative way of working. He sees the sun, learns its patterns, takes a day hike if he wants to. He treasures the time with his new rock star wife and baby boy, Sagan, in the beauty and serenity of Topanga Canyon. And he keeps making music. Great music. In a new way. Fade to black…

All of that is true, and you can find most of the Eric Valentine origin story on the internet. But again, it’s just the surface. The reality is much better.

The Road to Barefoot Recording

First of all, Eric Valentine would shun the Hollywood intrusion. He’s a private, humble and genuinely nice guy who just loves music and sound. But he’s been in a cave, as he says, for about 30 years now. He’s loved every minute of it, of course, but things change, as they have since he first moved south from the Bay Area, leaving behind a warehouse studio he affectionately dubbed Hunk of Shit.

“That was one of the most fortuitous recording situations I’ve been in,” Valentine says of HOS, his fourth or fifth iteration of self-built studios at the time. “The sound room sounded amazing. The control room was easily the best-sounding I’ve ever been in. And it was a total pile of junk. We threw the control room together—foam on the walls, I built the soffits myself with leftover construction materials. And everybody who went in there was amazed by how good the UREI 813Cs sounded in that room.

“I ended up with this naïve sense of how easy it was to get a good-sounding control room and a good sounding studio space,” he continues. “So when I ultimately left that space and moved into Crystal, and basically inherited an already designed space, I figured I would do it exactly the same way I did before. But then the dimensions, materials and everything else was different. The room was really difficult. It took me years to get that room to the point where I was happy sitting in the mix position, with a satisfying and reliable low end.”

The irony was not lost on him. He moved to Los Angeles in search of a ready-made studio, having tired of building the previous five. But in 2000, he found a lot of studios had been carved up into smaller rooms. He wanted space. After a year of searching, he found it in the legendary Crystal Industries Recording, built by Andrew Berliner in 1967 in a former post office building and home to countless hits, including Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life. The 9-foot Yamaha grand piano was still there.

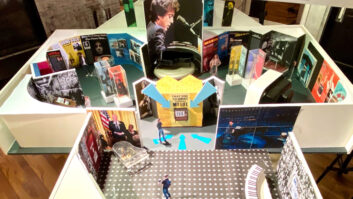

“Crystal was perfect,” Valentine recalls. “But it was terribly neglected at this point. The rats had really taken over. To this day, though, purchasing that building is still the smartest business decision I’ve made in my life. I knew I would have to make a lot of changes, and I wanted complete freedom. I wanted it to be my Willy Wonka experimental music laboratory, and I didn’t want anyone preventing me from doing anything. If I want to put up a wall, or take out a door, I want to do it.

Related: Taking Back Sunday—Reunited Band Lets Songs Become Their Own Experience, by Sarah Banzuly, July 1, 2011

“So I shrunk the control room and had enough space to add a machine room and an iso booth. I did away with the actual studio window and used video cameras and monitors. The main sound room was all carpeted. I put in hardwood floors and some acoustic treatments. Then I battled with the control room for seven to eight years. For the last ten years, it’s sounded amazing.”

The Road to UnderTone

But then, around 2010, whether the tinkerer in him just needed a new project or frustration with his tools reached a boiling point, he decided to replace his Neve 88R console in Studio A. Valentine loves Neves. He bought his first 8038 back in the Bay Area with T-Ride money, followed by an 8128. When that reached the end of its lifespan, he bought the 60-channel 88R, a great desk he says, fabulous. There was just too much of it for the way he liked to work.

“I was going to put together my own custom console based on an input module I knew I liked,” he recalls. “A vintage Neve 1084 or these Quad Eight 4-band EQs I like. That’s what I was looking at. One console. For me.”

Soon after moving to Los Angeles, however, he had met Larry Jasper on a recommendation when he needed work done on his Ampex MM1200 tape machine. Over the years, Jasper would suggest modifications to Valentine’s vintage gear, and Valentine would remain skeptical. But every time, Valentine says, the mod was more musical, whether on an LA-2A or a 1074.

“It always worked better than the original,” Valentine says. “Larry is a savant, the most brilliant audio circuit designer I’ve ever encountered. And I’ve worked with a lot of techs over the years. Larry was going to help me get a frame together, build some basic summing and busing, and that was it. Then I kept wanting more flexibility in the equalizer, and asking if we could mod the Neves. Finally, we said let’s just do it from scratch.

“For the money I got selling that Neve 88R, I built two custom consoles from scratch for my control rooms. It was an even trade,” he adds. “But the EQ we came up with was so unique—the design approach was something nobody had ever done before, so many things in the circuitry—we decided to try to sell it. The first thing we did was start building custom consoles for other people. Greg Wells got the first one, I believe. We built a total of eight consoles, the first two for Barefoot Recording, the other six around the world.”

More products followed, feeding off the synergy of the first-floor studios and the second floor electronics shop. If engineers had a problem, the shop could usually solve it. Likewise, the studios provided a test bed for the designs. The company’s first real commercial product, the MPEQ-1, provides a shining example.

“I really like the Neve 1084,” Valentine says. “It’s flexible in the high frequencies but still class A. And it’s a broad equalizer, wonderfully musical sounding. But there were times where I needed to be extremely surgical. For those, I used the GML 8200 or this Orban for dramatic carving. They’re all rackmount, so I would have to pull my head away from the sweet spot. I wanted an equalizer as musical as these vintage EQs, and as powerful and flexible as any EQ ever made. And we built it.”

Related: Maroon 5—Taking Time to Get It Right, by David John Farinella, Nov. 1, 2007

All this time, Valentine is continuing to make records, other producers are locking out Studio B, and more products follow, including the MPDI-4 and the unFairchild.

Barefoot Opens Up

In 2012, while the first consoles were being made, Tim O’Sullivan, a young engineer from Phoenix who was running, then assisting, at Capitol Studios, met Valentine through the studio and began moonlighting after hours for Undertone, all on the up and up. He learned wiring and electronics on the job, same as he learned recording. He put knobs on the first Undertone consoles and was there for the first run of 100 EQs and ten unFairchilds.

Then he left to sow his own oats, ending up in Brooklyn after a stint on the road and engineering all of producer Sam Spiegel’s projects. Then, in June 2018, he came back to help create the new Barefoot Recording. He’s a resident producer/engineer in Studio B, along with Joe Napolitano and Nick Zinner, and he’s also studio manager and chief engineer. Part of the family.

“I owe so much of my experience to Barefoot and Undertone,” O’Sullivan says. “I was wiring, stuffing circuit boards, getting scribble strips made and helping around the shop. Engineer Bradley Cook, who runs the Undertone tech shop, is just incredible—he can make anything. It’s a really unique place because we have that skill set and we have that as part of the way the place is set up. If there is a technical problem, we make the tool we need to solve it.

“My friends and I started making records with an mBox,” he continues. “It was super simple. We made our first records in GarageBand. All these tubes and consoles, that was our dream. We didn’t think it would be possible. Now I have a chance to continue a legacy and work with this equipment every day. It’s been amazing to be in a facility where analog or digital can be a choice, and you can choose the best techniques for the music.”

O’Sullivan is apparently doing his job well. On the day Mix called, there were putting finishing touches on the mix of a posthumous Leonard Cohen project, and the rooms are booked consistently. But O’Sullivan is confident they can accommodate everyone. “If you really want to record here, trust me, we’ll make it work.”

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get it delivered right to your inbox.

Meanwhile, Valentine is enjoying life at home and at his new Topangadise Studio, in a separate structure on his property built from the ground up to avoid all the mistakes made over the past 30 years, he says with a laugh. This wasn’t a sudden move. He had planned the transition well in advance so that he could keep working, while staying close to his new family.

“I had been telling Eric for so long how amazing the studio is, and how it just needed to be propped up to the legend that it is,” says Grace Potter. “There’s something about that space that calls to an artist. I kind of like the dirt and the grime. The layers and decades that have unfolded are still very palpable. There actually are ghosts in the walls. I felt it instantly.”

Valentine had been recommended to Potter as a possible producer two records back. She recalls walking into the studio and “here’s this guy on the floor, barefoot, stringing cables and barely looking up. And I think, ‘This is perfect. I love this.’ Every artist who gets the privilege to record in there, you feel it, but it’s nice to be reminded of it. You get to work all day in these rooms, but you sometimes forget how many incredible records were made there.”