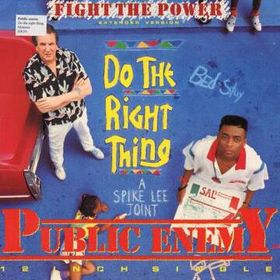

It is hard to forget the impact of the opening sequence of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989). Actress Rosie Perez, her face a mask of determination, does a combination of dancing and shadowboxing, a fierce and beautiful image that sets the stage for the movie’s depiction of racial tensions, anger and, finally, revolt against racial injustice. Equally memorable is the song she was dancing to, a fiery hip-hop track at once jarring and funky, like almost nothing else heard up to that point. The basic groove sounded like a James Brown cut deconstructed and rebuilt again with scrap metal. The chorus, with its heavily distorted and layered samples, called to mind a group of box radios tuned to different stations.

Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” was a quantum leap for rap music. In the late ’80s, hip hop songs used only a few samples each, with the beat often created with single break from an old funk recording (frequently, at the time, Clive Stubblefield playing on James Brown’s track “The Funky Drummer”). But “Fight the Power” featured a large number of samples that were layered and altered so heavily that it was hard to identify the sources. (Two of its creators, when pressed to remember, could only name a few.) Recorded not too long before the legal clampdown on sampling, “Fight the Power” was a masterpiece of sound collage.

The song, along with the success of Public Enemy’s previous album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, also helped usher in a brief period when radical black politics pervaded mainstream hip-hop. Politics had certainly always been in rap (Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message” and early Run-DMC), but Public Enemy was arguably the most politically extreme group to achieve sustained commercial success. Their backup dancers wore combat berets and held fake uzis, emphasizing the group’s militant views; their raps were filled with pointed criticisms of the white establishment. On “Fight the Power,” rapper Chuck D labels Elvis Presley a “racist,” with Flavor Flav chiming in “Yo, motherf*** him and John Wayne!”

Public Enemy formed on Long Island in the early ’80s, while Chuck D (aka Carlton Ridenhour) attended Adelphi University as a graphic designer. He and Hank Shocklee, later the group’s executive producer, were both working at Adelphi’s radio station, WBAU. They were later joined by Hank Shocklee’s brother, Keith, the record maven of the group, and Eric “Vietnam” Sadler, forming Public Enemy’s production team (known as “The Bomb Squad”).

An early demo tape, “Public Enemy No. 1,” reached the ears of Def Jam Records co-founder Rick Rubin, who courted and signed the group. In 1987, Public Enemy toured as an opening act for the Beastie Boys to promote their first album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show. With sampling done using a fairly primitive 8-bit Ensoniq Mirage sampler, it was more rudimentary and less commercially successful than next year’s follow-up, Nation of Millions. Nation showed Public Enemy growing creatively, exploring more complex sampling with the more advanced Akai S-900 and E-mu SP-1200 samplers. The album broke through to Platinum status, despite a lock-out by commercial radio.

It was at this moment in the group’s rise that Lee asked them to contribute a track to Do the Right Thing. Lee originally envisioned it as a collaboration between Public Enemy and jazz composer and trumpeter Terence Blanchard. “Immediately I didn’t feel it, not because I don’t have respect for Terence Blanchard and his work. It was like trying to mix apples and donuts — two different worlds,” explains Hank Shocklee. Nor did Hank Shocklee like Lee’s idea that they rework the African-American National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” “I wanted to do something that exemplified the sentiment of the inner cities, the streets, something anthemic because [Spike] wanted an anthem, basically.”

Convincing Lee to let them do their own thing was no easy matter. The group spent two meetings arguing with him over the idea. “We were going at it toe-to-toe,” Hank Shocklee recalls. “Spike is a very strong-minded and strong-willed person.” Ultimately, PE decided to follow their own instincts, crossing their fingers and hoping Lee would like the results.

“Fight the Power” was recorded at Greene Street, one of the main studios where hip-hop was made in New York during the late ’80s. Greene Street had A and B studios with two different consoles, an Amek APC-1000 and a Trident TSM. While they generally alternated recording on the two consoles, “Fight the Power” was mixed and mainly recorded on the Amek, partly for that board’s automation capabilities. “We had a lot of rides and a lot mutes,” says Keith Shocklee. “Automation was our best friend.”

Public Enemy’s process of composition was a collective one, closer to that of a rock band than many hip-hop outfits. They would get together and essentially jam, collectively and individually, until they found something they liked. “The key of PE’s style was that it was clean and dirty; it was tight and messy,” Hank Shocklee says. “Everybody is pitching in ideas, and the idea that was stronger is what ended up on tape.”

PE was notoriously heavy on preproduction. “It was all ready to go on the SP-1200,” says Rod Hui, who engineered that album, as well as “Fight the Power” and the follow-up, Fear of a Black Planet, with Nick Sansanos. “Eric ‘Vietnam’ Sadler was the main person in control of that. He was a great programmer. Everything would funnel to him, and he would make it all make sense, and then I would just lay it down on 2-inch.”

Classic Tracks: A Tribe Called Quest’s “Can I Kick It?”

A key to the lo-fi sounds found on “Fight the Power” and other Public Enemy records of the period were the technical limitations of their samplers, which the group enjoyed and embraced as part of their noise-based aesthetic. The S-900 and SP-1200 used 12-bit samples — more advanced than the Mirage, but lower than today’s standard of 16 bits. Hank Shocklee explains that he likes the low-res sound because “you can’t pick out the exact instrument and things that are going on, and it kind of meshes it all together, so the frequencies of where the guitar and the bass come in are not clearly defined.”

This was enhanced by the fact that the group often used longer sample loops than the equipment was intended for. “I think the SP-1200 had eight or 12 seconds tops for all 16 pads,” explains Hank Shocklee. “It wasn’t designed to do what we were doing. It was just designed to put in kicks, snares, hi-hats, rides. To get more time, we would speed up the record, play it at 45 and we got almost double the time.” Once the sped-up sample was loaded in, it had to be pitched down, resulting in a further degradation of the sounds. Add to that the fact that the SP-1200 cut off the ends of its samples sharply. “The cut-off gave it a rough sound, a real edgy sound,” says Keith Shocklee appreciatively.

Another key to Public Enemy’s unique sound was their beat-creation process. Unlike many of their contemporaries, who would lift a beat from a recording more or less intact, PE would frequently doctor beats to create a different kind of rhythm than the original.

PE also often played their own individually sampled kicks, snares and hi-hats over whatever rhythms they had looped. Because the natural reverb that came with these individual drum samples would “wash the sound back,” according to Hank Shocklee, he and Sadler layered the kicks and snares. Thus a single kick would be a composite of several samples that covered different parts of the frequency spectrum to give it a fuller, more powerful sound.

In terms of the rapping, Hui recalls that much of Chuck D’s writing occurred spontaneously in the studio. “Ninety percent was inspired by the tracking,” he says. For D’s vocal chain, Hui used a Neumann 87 microphone, an API mic pre, an 1176 compressor/limiter and an LA-2A compressor. He remembers that the rapper never liked to punch in; if he made a mistake, he would simply retake the entire vocal. It was actually Hui who mixed the song on the Amek console, mixing it onto half-inch analog tape at 30 ips on a Studer 820 tape machine. (Hui also mixed Nations and Black Planet.)

When the song was completed and delivered, the group didn’t hear back from Lee. Hank Shocklee was skeptical that he would accept the song. But when the movie came out, Hank Shocklee ran into some people who had been to a screening. “They said, ‘Yo, “Fight the Power” is all over it!’” he recalls. “I guess that was a way of Spike saying that he liked it without telling us that he really loved it.”

Both movie and song proved momentous for their creators. Do the Right Thing was Lee’s biggest film and earned him an Oscar nomination for the screenplay. “Fight the Power” topped the rap charts and helped push Public Enemy’s next two albums into Billboard‘s Top 10. Public Enemy’s major record sales faded after the early ’90s, coinciding with (though not necessarily due to) a change in their sound as new sampling laws made the collage techniques of “Fight the Power” and Nation too expensive. The group continued to make music for a smaller but devoted following; their latest album is actually a collaboration with another radical rapper from the late ’80s, Paris. Hank Shocklee, after parting ways with PE, has gone on to produce records by other artists and is currently writing a book about the recording of Nation of Millions; Keith recently contributed to rapper Xzibit’s latest album, Full Circle. So while Public Enemy and much of politically oriented rap have disappeared from the charts, both thrive outside the mainstream.