Film composer Gary Chang has always had an active interest in ambient and minimalist music and the possibilities of expanding the potential of the recorded musical soundstage. But until recently, he has been limited to the use of reverb and delay, signal processing gear and mixing techniques. Today, he has the ability to visualize his compositions from the outset as surround pieces and single-handedly produce and mix them in 5.1.

“Since the ’70s, I have had an active interest in ambient music,” Chang says. “In much of my film music, I have tried to employ this spatial sensibility, but it has been a daunting task until recent 5.1 developments.”

Chang, whose credits range from films with John Frankenheimer (The Island of Dr. Moreau) and Emmy-winning cable features (George Wallace and Andersonville), to working with critically acclaimed artists such as the Turtle Island Quartet and Robbie Robertson, has just completed Rose Red, a six-hour ABC miniseries that was written and produced by novelist Stephen King. The made-for-TV movie comprises three feature-length episodes, with each broken into seven acts. The sound was done in 5.1 surround, so Chang was able to create a much more dimensional soundtrack.

“The very nature of Rose Red being about a haunted house requires a certain amount of Bernard Herrmanesque music — classic film scoring,” Chang explains. “When our group of psychics meet a ghost in the mirror library, I placed the ‘score’ in its classic position, front LCR. Meanwhile, the ghost motifs, ethereal and soft, ‘appear’ in the room, where they are not competing with the movement of the orchestra. I placed quieter musical passages in the back, while louder, traditional stuff played at the front. The result is a sort of disquieting effect, like someone whispering in your ear that your shoe is untied, while in front the starter is about to start the race.”

Chang draws from a number of sound sources to augment the tracks, including a large collection of exotic percussive instruments — Tibetan bells, singing bowls and a glass harmonica made by Gerhard Finkenbeiner. Sometimes these instruments provide dramatic touches in the surround field.

“I have many samples of John Bergamo’s instrument collection, including some large aluminum plates, which I suspend over a timpani [which acts like a resonator]. When these instruments are played, the sound literally surrounds you in a room. They radiate omni-directionally,” says Chang. “With 5.1, I can finally place this stuff in the room, where it sounds natural, instead of trying to cram it in the proscenium, behind the violins. In Rose Red, I use this family of bell-sound instruments to create the subliminal undertow of the undead spirits in the house.”

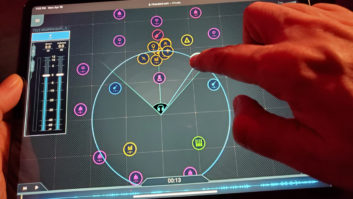

One recently acquired piece of gear that Chang found very useful in rendering the placement of elements like the Tibetan bells was the TC Electronic System 6000, which he used extensively in Rose Red.

“It’s funny how certain things can dramatically change your perspective on your creative environment,” he says. “I have been recording and mixing in my room for years, but when I installed the TC System 6000, something happened. The VSS reverb algorithm allows for precise positioning of sounds in the 5.1 field. I could put a noise right next to me!”

Aside from the obvious features, like auto-panning and such, the System 6000 has an algorithm called UnWrap, which takes stereo information and re-processes it into 5.1. Chang found this extremely useful in helping him reconfigure certain audio files for the soundtrack.

The Rose Red score is a combination of orchestral and electronic music. The selected orchestral cues are transcribed for Chang’s orchestrator, Todd Hayen, using Emagic Logic Platinum. Once the sketches are checked, they are posted on the orchestrator’s FTP site via e-mail.

“For the orchestral recording, we chose to record the session in Pro Tools, with a DA-98 backup,” Chang explains. “For the session, we used an Apogee AD-8000SE, with Digi and TDIF interface cards. We provided clicks and reference music tracks by copying the original Pro Tools sessions and stripping them down. On some cues, we added as many as 32 tracks to the existing session, all on a standard Mix Plus system! We brought a total of 90 gigs of disk storage to the session.”

Back at home, Chang added any additional electronic music sweetening or certain solo instruments (guitar, for instance). Various episodes of the recording session were sampled into Sonic Foundry’s ACID for tempo or pitch modifications, or sampled into a Synclavier.

“During these recording sessions for Rose Red, we discovered that we improved the sound of the recording even more by doing stuff like changing the AC cable of the mic pre!” Chang recalls. “Tara Labs, which has been making ‘interconnects’ for the audiophile industry for 16 years, makes these AC cables. The noise-deterring qualities were most evident when we swapped the video monitor power cable. It yielded much smoother high-frequency response that everyone could hear. I’ve got them on my monitors, and intend to eventually swap out every AC cable in the studio.

“Since I am delivering final music mixes in complete acts, Pro Tools gets quite a workout,” adds Chang, who goes on to further explain his process for the project:

“A typical example would be Night 3, Act 1. In this section, I have continuous music from beginning to end. So, as many film composers may do, I write and produce such an expansive piece (about 12 minutes) as shorter, interconnecting segments. The ‘A’ segment has a minimum of 16 tracks from the orchestra session, and 32 tracks from the synth rig. Add to this the 5.0 track that becomes the final mix, and that is 54 tracks. Now double this, so that you can record the ‘B’ segment on clean tracks [in many cases, the ends and beginning of the segments overlap] and that gives us 108 tracks in the session! Add, of course, a 5.0 aux send for reverb returns, and various other aux inputs for plug-in instruments such as the Access Virus, additional master faders to control the reverb sends, and, well you get the idea — these are some huge sessions.”

Because Pro Tools has only 64 voices, Chang was busy selecting and activating/deactivating the various voices to record the segment that he is mixing. Once the “A” segment is recorded and mixed, all of the tracks except the 5.0 mix tracks are deactivated. That allowed Chang to activate the “B” segment tracks for recording. With the mix tracks added, Chang was running 59 tracks during each segment’s recording and mixing.

“It’s pretty cool to see the system operate with so much going on — I tend to run out of TDM slots before I run out of DSP,” Chang exclaims. “While mixing, I use a 42-inch Sony monitor, which saves my eyes.”

Once an entire act was mixed, a mix-only version was created and a CD archive was burned. This verified copy was given to the music editor, Sherry Whitfield, who then transfered it to the final dubbing stage media.

“On occasion, when the session was too large to fit on a CD, we used hard drives,” says Chang. “Imagine 21 sessions, as many as 130 audio tracks wide with a session length of 25 minutes! That’s a truckload of storage!”

Rose Red marks the second project that Chang has done with King, the first being the Emmy Award-winning miniseries Storm of the Century.

“I have been blessed in my career to have worked with many of the great filmmakers and storytellers of our business,” says Chang. “One of the real pleasures of working on Stephen King projects is to read his screenplays. Both Storm of the Century and Rose Red are original written-for-TV screenplays, not adapted from novels. In many ways, these two pieces are about the choices that people make — decisions that govern people’s behavior.

“What is great for me is that Stephen chooses to employ real emotions in his work,” Chang says in summation. “Even if the supernatural is involved, his characters are driven like real people. It is the extraordinary circumstances that expose issues for us to examine. It is great for me, because I can focus on those real emotions when I am writing the music.”

Chang at Home

Chang’s studio runs off of four computer systems:

- 550MHz Pentium III w/320-megs RAM running Propellerhead Reason, Sonic Foundry ACID and NemeSys GigaStudio. Audio card is a Soundscape Mixtreme, w/16-channel TDIF I/O.

- 330MHz G3 that runs the Synclavier. (The most recent version of the Synclavier runs the old audio hardware with a Power PC, weeding out all of the old, outdated disk, optical and tape drives.) The Synclavier has 96 voices, with 192 megs of RAM.

- 450MHz G4 dual processor that runs Pro Tools, Logic Audio and Reason. The Pro Tools MIX system has five FarmCore Cards (six total), Pro Control and 64 inputs.

The first 32 are Apogee AD-8000 interfaces, which provide digital I/O with the Windows system and high-quality analog inputs for the Synclavier.

16 are Digidesign 888/24, which interface with a TC Electronic System 6000, used for its 5.1 reverb, 5.1 Finalizer and stereo-to-5.1 UnWrap algorithms.

A Digidesign 1622 provides 16 synthesizer inputs for the Waldorf devices.

- 500MHz Titanium Powerbook w/512 megs of RAM and Magma PCMCIA expansion chassis. Audio card is a Delta 10/10 24/96 interface.

“My Powerbook can run Pro Tools on the road, although I have to pilfer from my main system to do so,” Chang says. “Instead, I run Logic Audio and Reason on this computer. Reason on the Powerbook is great! It’s like a transistor-radio version of the big system.”

Chang’s room is an industry-standard theatrical room, utilizing THX-approved components (Meyer HD-1 LCR, JBL surrounds). “The film industry has industry standards. Everything is absolute. Because I’m involved in film music, I’ve assembled an industry-standard listening room that virtually matches several important dub stages downtown. I couldn’t do what I do without industry-standard monitoring. The speakers I choose and the room that I listen to them in are the most fundamental components in my project studio.”

— Rick Clark