Back at the beginnings of modern civilization, soon after the invention of the wheel, the recording of music was often done through a haphazard collection of 2-track radio consoles slung together with raw wire and powered by fossil fuels. Human beings spilled their souls onto long, winding strips of plastic tape, rearranging iron particles and rewriting history. The invention of the wheel, in our case, was the invention of the multitrack tape recorder. What followed was the perfect storm of artistic ideas fueled by ravenous capitalism, creating the era of Custom Consoles.

In 1967, a year after the groundbreaking 8-track recording of Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys, Ampex presented the first commercially available 16-track machine, the MM-1000, and the landscape of the recording industry changed. Meanwhile, George Martin proved with The Beatles’ multitrack masterpiece Sgt. Pepper’s that the engineer and producer were now, more than ever, a creative force in the making of popular music.

But one major problem existed: There was no standardized way for the audio engineer to use a multitrack recorder. In essence, you needed two separate mixers to do the job—one to route mics to the recorder and one to mix the multitrack’s playback for listening. Early recording studios like Sun Studios in Memphis often used broadcast equipment or had an improvised collection of two or three rotary-knob mixers tied together. Fledgling companies like Spectrasonics, Neve, API and Trident, and lesser-known ones such as TG, Quad Eight, Sphere, Electrodyne, Calrec, Aengus and Helios came to life. They could build a personalized worksurface, combining mic amps, line amps, routing, metering and monitoring. You could request in-line faders in lieu of rotary pots, any combination of metering and routing, specialized equalizers and compressor/limiters, two or four outputs—anything you desired. Hundreds of these consoles were built and installed during the early ’70s.

Brian Wilson working in Studio B at Ocean Way on the Dal-Con Custom Console in 2010

Photo: Mr. Bonzai

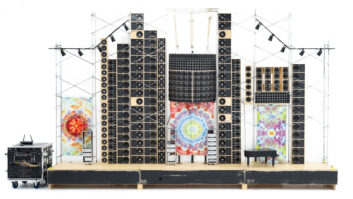

The first Customs appeared in studios like Stax and Ardent in the States, and Olympic and Abbey Road in London. These consoles were limited by today’s standards and needed trained staff engineers to operate them, but they were still far more versatile than the commercially available broadcast consoles at the time. In Memphis in 1970, Andy Johns and Terry Manning mixed Led Zeppelin III on Ardent’s new Spectrasonics console, built with 12 mic/line channels, linear faders and four outputs. They used the studio’s 8-track Scully tape machine to play back the master tapes they had recorded at Olympic, mixing down to a Scully 4-track. The format was so new that they didn’t even monitor through two speakers, but listened to all four outputs at the same time through a constellation of JBLs suspended from the ceiling.

By the mid-’70s, everyone had a Custom. L.A. studios like Sunset Sound, Western Recorders, Hollywood Sound, Capitol, Wally Heider and Cherokee employed designers to help create each studio’s unique “sound.” Technicians like Frank DeMedio, Robert Bushnell and Deane Jensen dominated the L.A. scene. Grandmaster Studio in L.A. had a crazy three-sided Custom that would rise up when you mixed so you could easily reach the controls like you were in a spaceship. Indigo Ranch had a Custom with Deane Jensen transformers and Aengus EQs in a studio overlooking the ocean in Malibu. Crystal Studios in Hollywood had two Customs built by owner/designer Andrew Berliner; his proprietary designs included groundbreaking digitally controlled amps in the faders.

The Spectrasonics Custom Console that Terry Manning used to mix Led Zeppelin III at Ardent Studios in Memphis, circa 1969

Photo: Courtesy Terry Manning

One of the most famous and unique Custom Consoles still in existence is a daily driver that lives at Ocean Way in L.A. Bill Putnam first commissioned the Custom in 1973 for Studio 1 at Western Recorders on Sunset. When Allen Sides acquired the Western facility and moved Ocean Way Recorders into an adjacent building, the Dal-Con—named after its unique op amp—was moved to Studio B, where it sits today. Nicknamed the “Baseball Bat” by mixer Chris Lord-Alge, this console is known for its fast slew rate, something remarkable for the early ’70s—and still amazing today. As technology changed and recording went from 16 to 24 to 32-track, the Dal-Con was modified and expanded to accommodate the new formats. Sides added a bank of 40 API 550A equalizer modules in a side rack to augment the simple passive EQs in the original console. Next, they expanded the Dal-Con with an API 1604 sidecar, tying it into the busing on the main console. The result is a sprawling mish-mash of an awesome console that’s as relevant today as it was when it was built (being used to record Natalie Cole’s Unforgettable, Radiohead’s Hail to the Thief and Kanye West’s Late Registration, among others).

Sunset Sound in Hollywood still operates two of its originals. The Custom Consoles in Studio 1 and Studio 3 were designed by Eric Benton, Frank DeMedio and Deane Jensen, and feature their completely unique Sunset Sound mic preamps. Because Sunset was a dealer for API, they designed their Customs to incorporate the desirable API 550A EQs, building them directly into the worksurface. At one time, Studio 2 also had a Sunset Custom Console. All of Van Halen’s greatest albums were recorded on the Studio 2 board. But all those records, all that fame, was not enough to prevent the Custom’s demise.

Detail of the diamond-shaped faders from Crystal Studios consoles

Photo: Courtesy Thomas Johnson

The newest Custom Console: Terry Manning remotely adjusting a fader level on his iPad controller

Van Halen at the Sunset Sound Custom Console in Studio 2, circa 1979

Photo: Courtesy Sunset Sound

THE NEWER NORMAL

As the ’70s revolution raged on, Trident Studios in England had been making its own Custom Consoles called the A-Range and B-Range, and in 1975, the studio unveiled the new Series 80 console, which had a very standardized layout. The Series 80, 80B and 80C were mass-produced with a minimum of 32 channels for which the controls were mounted on long strips instead of individual modules. Personalizing was limited, and for the most part was not needed. Each channel had a mic/line amp, 24 buses, EQ, eight cue/effect send outputs and a linear fader. Each 80 Series also had a built-in eighth-inch TT-style patchbay, a center section with send and monitoring controls, and a standardized stereo bus—everything you might want for recording in a very streamlined form. You didn’t need to be a technician to buy one, and any independent engineer could navigate a session on one of these new-generation consoles without needing any more instructions than where to turn on the lights in the room. One by one, the big lunky Customs were replaced by MCI, Harrison, Amek, Soundcraft, Neve V and Solid State Logic. By the 1990s, most of the great Custom Consoles had long been replaced.

My first personal encounter with a true Custom was when I worked at a studio called Bear West in San Francisco in the ’80s. Its old API DeMedio in Studio A was big and square, and had a vast patchbay of brass ¼-inch plugs with just about any patch point you could dream of. It had a fake plastic wood veneer that was chipped off on the corners and a worn Naugahyde bolster that was cracked and peeling. But, oh, it had soul. It sounded thick, golden-brown and grainy, and would often spit at you. I loved it. I was disappointed when the studio owner replaced the board for a cookie-cutter Sound Workshop. Not that the Sound Workshop sounded bad; the API DeMedio just sounded too good.

RE-INVENTING THE WHEEL

Today, with the advent of digital, the entire idea of worksurfaces is quite different from how it was 40 years ago, but the concepts and the appearances are surprisingly familiar. It may be a picture of a knob or a fader that you are manipulating on your screen, but its purpose is the same. Whatever it was in that recipe of graphite, copper, resistors, potentiometers, plates, strips and islands will hopefully be offered to you soon as a plug-in. There’s nothing wrong with appreciating works of art as you would by having a copy of a Matisse or a Dali on your wall. Not everyone can have an original, and in an abstract way we can now all have our own beautiful Custom Console masterpieces.

Sylvia Massy is the unconventional producer and engineer of artists including Tool, System of a Down, Johnny Cash, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Tom Petty and Prince. She is a member of the NARAS P&E Wing Steering Committee and Advisory Boards, and is a resident producer at RadioStar Studios in Weed, Calif.