Raymond Herrera probably didn’t think his percussive skills wouldlead to a second career in the video game industry. But three yearsago, when his drumming for industrial band Fear Factory led to workproviding music for games such as Test Drive Cross-Town (Atari),Gran Turismo 4 (Sony) and Dead to Rights 2 — Hell toPay (Namco), he founded the aptly named Herrera Productions.

“It’s very exciting to be working in the video game market,because I’ve been into video games since the 2600 came out when I was10,” Herrera says. “I started Herrera Productions because alot of projects started popping up that didn’t want heavy music likeFear Factory. If they wanted something heavy and fast, we could stilldo Fear Factory. If they want something different, I do it through myproduction company.”

GETTING INTO SOUND EFFECTS

Starting the company enabled Hererra to move into sound effects andvoice-overs. Steve Tushar, one of Herrera’s first hires, is one ofthree sound designers in the sound effects department. Tushar, who cameinto the video game market from the film industry, says that hiscontinued work in film has helped his game work. Indeed, Tushar hascollected sounds from Foley artists who have performed effects work onsome of his film projects. “Sometimes I’ll use my connections inthe film industry to get sound for my video game work,” Tusharsays. “I’ve done that once in awhile to get some sound effectsfrom Foley artists, like sword-dropping sounds or wooden shieldsfalling on concrete. It’s good when you can get some original soundsrather than library stuff. That’s some of the best stuff Ihave.”

Both Foley sounds and Tushar’s effects library have been collectedinto about 400 GB of hard drives. His main audio editing tool isSteinberg’s Nuendo. “It makes every other program seem like atoy,” he says, “especially when you’re dealing with audioand doing editing and crossfades and inside-out fades. You can slipaudio while keeping crossfades intact without having to throw them outlike in other systems. If you’re doing one-second loops and you’ve gotall these fades, you can actually shift the audio internally withoutdisrupting anything and you still have the one-second loop.”

In addition to Nuendo, programs such as Steinberg’s WaveLab andplug-ins from Native Instruments get the call. Tushar adds few effects,relying mostly on pitch bending and pitch shifting. “Sometimes,I’ll put a really short reverb on something to make it sound morestereo. Other than that, you don’t use many more plug-ins, because youneed to make things ultra-short. Maybe I’ll use a Doppler [effect]plug-in for certain things, but for video games, it’s pretty basic.It’s all about finding the right sounds, laying them together, cleaningit up and bouncing them down, and hoping it matches what they’vegot.”

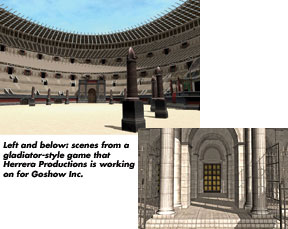

Tushar says creating short sound effects is one of his biggestchallenges. “On a gladiator game, they asked us for a wooden cartthat was rolling. They wanted a one- or two-second loop, and it’s hardto get it to loop without it sounding stupid and not hearing repetitionover and over that’s really annoying. So, a lot of times I’ll try tofind some kind of rhythmic thing that has bumps in it that actuallywill make sense.”

Tushar delivers sounds to the programmers via e-mail. He explains,“I’ll take the .AIFF files and zip them up to under 5MBattachments, which you can get quite a bit of sound in, consideringmost of them are under a second anyway, and e-mail them.”

WE’VE COME A LONG WAY

Before the advent of such gaming consoles as Microsoft Xbox and SonyPlayStation 2, audio professionals had to deal with some fairly strictcompression rates. Rather than the 11- or 22kHz rates they faced then,composers and sound designers are free to work up to 44.1 kHz.“We don’t really need to compress too much and [programmers]handle the compression a lot on their end of things,” Tusharsays. “We just deliver .AIFF or .WAV files for the most part andthey compress it down. The good thing now with all the PC games is thatthey can actually have almost an unlimited sound per level, but theypretty much allocate how much they want to use to load up. It’s notlike the old days of the PS1 and the Nintendo when you really had tosquash things.

“You used to have to make sure everything sounded good at8-bit or lower sample rates,” Tushar continues. “I used tomonitor my sound effects with a lowpass filter on the output of myprogram, just to hear what it’s going to sound like muffled because itmight be playing only at 22 kHz or 11 kHz. You had to make sure thesound stuck out at lower sample rates, and then you’d have to bounce itdown to whatever they wanted. Sometimes they’d want delivery at 11 or22kHz, but now we can do everything at 44.1 for the modern gamesystems. I’m so happy now that I can work in full bandwidth. These aregood days.”

David John Farinella is a San Francisco — basedwriter.