About 45 minutes into the first date of the John Mayer Trio tour at The Fillmore in San Francisco last fall, the singer/guitar player stepped up to the microphone and exclaimed, “Ladies and gentlemen, the John Mayer Trio has just arrived.”

“Oh, yeah, that was in ‘Ain’t Gonna Give Up on Love,’ where all the nerves kind of went away and we did our thing,” Mayer recalls nearly a year later as his latest release, Continuum, is about to hit shelves across the globe. That trio, which included Steve Jordan on drums and Pino Palladino on bass, played a run of shows that included appearances at The Grammys and a tsunami benefit, documented in the live album Try!

What Mayer was attempting seemed bold: transforming himself from a somewhat whispy pop icon to a hard-edged blues/rock player. Truth be told, Mayer has always had that guitar-hero side lurking inside of him. It was bound to come out.

Those live dates gave Mayer the opportunity to clear out any residual nerves that may have cropped up once the red light flicked on for this new studio effort. “This record is nothing but a collection of discovery moments where I went, ‘I had no idea I could do that,’ and did it,” he reports. “In a lot of ways, I still feel like I have someone else’s record in my pocket. Here’s the thing: You think you have such a good idea of what you are capable of, and a lot of times you do have a good idea of what you are capable of. But what makes music so exciting is that, at any moment, if you try hard enough or if you commit yourself to the spirit of it, you can actually become more than you originally thought you were.”

The live dates also gave the three an opportunity to polish song arrangements, explains drummer Jordan. For instance, on the songs “Vultures” and “Gravity,” “I kind of knew what I wanted [‘Vultures’] to sound like, and I think John did as well, and I think it helped us to refine it by playing it on the road,” Jordan says. “We played that live and we played it for the live album, so for the studio version, we really know what works and what doesn’t work, down to the tempo and the nuances of how certain turnarounds have to feel. Getting the combination — and this is key — between the perfect studio take of it, but not losing the live energy, that makes it special. That’s very critical, because you can over studio-ize something and take all the life out of it. So we were cognizant of that when making the studio versions of these songs.”

Mayer, Jordan, Palladino and a cast of engineers that included Joe Ferla, Dave O’Donnell and Chad Franscoviak, who also doubles as Mayer’s live mixer, spent time in four studios — The Village in Los Angeles, Royal Studios in Memphis, and Avatar and Right Track/Sound on Sound in New York City — to record enough music to fill a pair of releases.

The recording dates started at Right Track/Sound on Sound, which is just off Times Square in Manhattan. “It was fun to be on 48th Street starting the record,” says Jordan, who co-produced the album with Mayer, “and walking out into Times Square in between takes. That was a necessary vibe.”

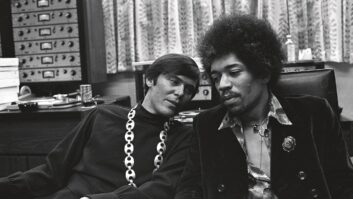

The Jordan/Mayer team dates back to a handful of songs on Mayer’s 2003 album, Heavier Things, where Jordan played drums, and then a number of Jordan productions (Herbie Hancock, Buddy Guy and John Scofield) where the guitar player lent a hand.

According to Mayer, he asked Jordan to produce what would become Continuum the first time they played together. “There was something that had never been accessed in me as an artist that Steve went for immediately, which was the immediacy of playing live in a room and recording it. Before Steve, I didn’t understand that what a microphone allows you to do is pick up what you are doing in a room and not target practice,” he explains. “You’re not aiming into the microphones; the microphones are there picking up what you are doing. I know that sounds remedial, but I had never seen it that way.”

Though Mayer has had a hand in producing his albums, “I was always the fake producer [before],” he admits. “I was producer when I wanted to be, and then when I didn’t want to be, I could go play Nintendo and have [Jack Joseph Puig, who produced the 2001 release Room for Squares] do vocal comps. What made this record different is that I stayed producer the entire time. Every single corner of this record I was there for and awake for, and it paid off.”

According to Mayer, Jordan handled the rhythm section and he handled everything else. “He hears things that I can’t because I’m not experienced enough to understand how things translate,” Mayer says. “I deal in vocal harmonies and the up-high stuff, the guitar parts. When we come together on that, it makes Continuum what it is, which is an incredibly beautiful, thick, groove-inspired rhythm section with my musical desire to be beautiful, my sonic ‘I want to be pretty’ thing, which I’m not afraid to say I have. The combination of his grit and my approach to it — there’s nothing else like it. We are kind of like a band, he and I. We achieve what great bands achieve, where it’s a combination of two people’s, or three or four or five people’s sensibilities that all come to make one. Steve Jordan is the sound of me, but better.”

The first recording date came the day after the tsunami benefit when Mayer, Jordan and Palladino, with engineers Ferla and Franscoviak, went into the studio to record the Jimi Hendrix cover “Bold As Love.” The next day they returned with additional bassist Willie Weeks, who was booked to play with Mayer and Jordan that weekend, and tracked “I Don’t Trust Myself (With Loving You).” “That was unbelievable,” Jordan remarks. “It’s not one guy playing and another guy overdubbing. No, that was done together. It was amazing and you can’t tell who was doing what. You can feel the magic of them playing their performance together.”

The level of musicianship and professionalism made recording this project a snap for engineer Franscoviak, and the fact that Jordan relies on all things vintage to get tracks to tape meant that it sounded warm when it got there. “The cool thing about it was that Steve has been doing this for so long. He has a very particular thing that he goes for,” Franscoviak says. “He wants things to sound natural and kind of old-school, but very unique at the same time. It’s all about the source stuff, not about fancy gadgetry.”

For Mayer’s vocal chain, Franscoviak says that most of the songs were recorded with a Neumann U47. For a couple of songs, he sang into a Neumann M269c, and on “I’m Gonna Find Another You,” which was recorded at Royal Studios in Memphis, he sang into Al Green’s RCA 77 ribbon mic. From there, the chain included a Neve sidecar stocked with 1073 mic pre’s and then a UREI silver-face 1176. “On a couple of songs, we did experiment with splitting his vocals into two channels — one of them would be kind of a clean and one of them would be kind of a gritty — and we would take the second channel and put it through a Fairchild 670 and really crush it,” Franscoviak explains. “Then we would either blend it together or choose one or the other for the mix.

“[Mayer] loves hearing his vocals really compressed, so he can be as dynamic as he wants to and it always sounds present to him,” he continues. “He likes way too much reverb when he’s tracking, and then when we proceed into the mix, it will be reeled in a little bit. Generally, I will compress lightly going to tape or Pro Tools, and then in Pro Tools cream it with usually the Renaissance Vox.”

Miking Mayer’s guitar rig depended on the song’s mood. On “The Heart of Life,” Franscoviak threw a ribbon mic in the middle of the main room as a pair of amplifiers boosted Mayer’s tracks. On the majority of the tracks, though, Franscoviak would put a Shure SM57 and a Beyerdynamic M88 right next to each other, about two fingers’ width from the guitar cabinet’s grille. He would take that track, blend it and send it to one channel. In addition, Mayer likes to hear room ambience on his guitar tracks. To accomplish that, Franscoviak would point either a pair of U67s or U87s about three feet from the edge of the semi-circle of amps, and then either a U47 or a Telefunken 251 in front of them all.

“Then, every once in a while, if he wanted a beefy sound, I would use a [Yamaha] NS10 speaker that had been reversed,” Franscoviak says. “I would put that right up on the cone of one of his cabinets to get that real low-end thing.” The best example of that, he adds, is the solo in “I’m Gonna Find Another You.” Mayer’s acoustic guitar chain was an AKG C24 microphone into 1073s.

To capture Palladino’s bass, his instrument typically went into either an Ampeg SVT or B-15 into an Avalon U5 mono instrument preamp and DI. “I took the throughput into his amplifier and usually put a FET 47 close up, and on occasion an RE20. Then I almost always put an NS-10 on his bass cabinet to get the ultralow stuff,” Franscoviak explains. “I would compress the DI and the FET 47 lightly, not in any way that would effect the dynamics of his performance, only for tonal reasons. I would never put a compressor on the NS-10.”

Jordan’s assortment of drums — which seemed to be endless, Franscoviak says with a laugh — were miked fairly conventionally: an AKG D 112, an RE20, a 421 or a Beyer M88 on the kick; snares got 57s on top and bottom; M88s on the toms; an AKG 451 on hi-hats; and on overheads, he either used a U67 or U87.

The only trick that Franscoviak used, which he fully admits stealing from Joe Ferla, was putting a Coles 4038 ribbon mic directly over the center of the kit, parallel to the ground and as close in as possible without impeding Jordan’s playing. “I generally compressed the snot out of that and I would run it through a Fairchild,” he says. “That’s a really interesting trick because you have all of your tight sounds, but you add that 4038 and it makes everything more exciting.”

He also put a U47 about 18 inches off the ground and four to seven feet in front of the kick drum for a very specific sound. “At some point, we were going to hit that low-end waveform just right and it was going to fill that kick drum out,” Franscoviak explains. “I would compress it a lot with an 1176, a lot harder than the overhead, because I wanted that low end to be there for every hit.”

Most of the songs that were recorded for Continuum were written before studio time was booked, but there were a couple of instances when the three worked together to come up with something new. “The songs that we co-wrote came out of a thing that we liked to call ‘free play,’ where we all got together and played to come up with something,” Jordan says. “We would get a groove going and then we’d hash out an arrangement. Then [John] would take it home and finish it lyrically. That’s how we came up with ‘Who Did You Think I Was’ [on Try!].”

And then there was “In Repair,” which featured Mayer and Jordan with guitarists Charlie Hunter and James Valentine and keyboardists Jamie Muhoberac and Ricky Peterson. “That was a complete studio inspiration lightning storm that was pretty amazing, actually,” Mayer recalls.

It was also nerve-wracking, which brings us back to that night in San Francisco. “There’s more at stake than anything you can play in Vegas,” Mayer says now. “That’s a lot resting on your coming up with something, and every time, we came up with something — every single time. I’m just following my instincts until my instincts don’t work anymore, and then I’ll defer to everyone else. There is no other gamble like that.”