I love it when the words “practical” and “realistic” are banned. Have you ever been given this invitation: “The goal is to make it the very best it can be, cost no object.” It has a tendency to perk one up.

What happens when a former child musician/successful technologist with plentiful resources, and a veteran studio architect give one another permission to dream up the ultimate music recording facility? The possibilities are manifold (i.e., many or varied). Certainly boundaries, like a deadline or limited mic locker, can be motivating forces. But after experiencing the studio firsthand, I would say the dream, design and manifestation of Manifold Studios spring from few boundaries beyond the laws of acoustics, thermodynamics and the capacity for the world to keep up with creator Michael Tiemann’s vision of what is possible.

Alex Oana at Manifold’s API Vision. All photography, unless otherwise noted, by Sally Gupton (sallyguptonphotography.net)

What is possible? That’s the preferred question around Manifold Studios. Owner/creator Tiemann, chief engineer Ian Schreier and designer Wes Lachot spent years creating multiple acoustic environments and a technical infrastructure that would, as often as possible, yield the answer, “Anything!” Manifold is a high-end, dedicated music recording studio and media production facility.

I was first introduced to Manifold Recording by studio designer Wes Lachot, whom I met while hosting the Vintage King-sponsored Neve Custom Series 75 demo at AES 2010 in San Francisco. Wes nonchalantly mentioned I should check out his latest project. Over the course of the next year I kept hearing about Manifold and even had one of my clients refer to it as inspiration for the studio he’s planning. Then this August my editor at PAR, Strother Bullins, asked if I’d like to engineer a session at Manifold to generate the magazine’s second-ever “Facility Review.”

Studio Re-invention

There are people who accept what the world presents them with, and people who invent what they want the world to be. Michael’s father was a theoretical physicist responsible for many inventions during the golden age of scientific advancement. In this case, the apple fell right under the tree, but during the golden age of the internet. Michael invented the first way for businesses to make money using open-source software. “Startups such as Google, Facebook and Twitter owe their early success to the quality of open source,” says Manifold’s website. Michael’s success allowed him to pursue his ongoing love of music listening and performance through the voice of the recording studio itself. In direct response to the passing of the era of great recording studios, Michael’s goal in creating Manifold was to combine classic studio acoustics with modern recording technology to best serve modern recording artists.

Technical Infrastructure

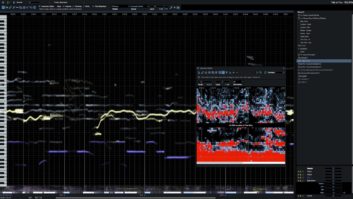

At Manifold, wherever it seemed to Michael that something should be possible — like fully integrating an all-discrete analog surround control room with an all-digital surround mixing control room — he relentlessly pursued the solution until it was possible. Machine rooms are impressive and intimidating: the sheer amounts of wiring, the loud fans, the blinking lights … For a music recording studio, I’ve not seen anything on par with Manifold’s Studio A machine room: multiple, fully-loaded, eightfoot steel racks, connected internally and between studios by wire bundled in more inches around over more miles than I’ve ever seen by a long shot.

Acoustics

According to Schreier, Lachot proposed Manifold’s initial architectural concepts after discussing the broad concept with Michael Tiemann. “This design is all about symmetry,” Wes told me during the session. “Think of the worst possible room acoustically: the cube. It’s perfectly symmetrical. Well, if you make a cube big enough, suddenly all of the problems turn into assets and you get consistent harmonic reinforcement across the spectrum.” Manifold is far from a cube, but by that example Wes describes how dimensional symmetry implemented on a large scale at Manifold has created a room that is a versatile instrument in itself. I used this phenomenon to my advantage.

Engineering

Speaking from experience, the challenge of assisting another engineer when you’re used to running the show is to develop the instinct for when to simply execute requests and when to just deliver the solution. Fortunately for our compressed two-day production schedule, Ian and I developed this shorthand quickly. By the time we started tracking vocals, Ian was engineering and running Pro Tools while I served as cheerleader and audience member for the singer in the vocal chamber. I came up with the input chains, but I did not have to change a single mic pre gain or patch a cable the whole session. Ian Schreier liberated me to stay in my creative space — such a gift.

Alex positions a Coles ribbon microphone for Jeff’s rhythm guitar tracks.

The Miraverse

It’s good to have a concept going in to a session; the same goes for when embarking upon building a recording studio. The Miraverse is Michael Tiemann’s moniker for a concept in recording that acknowledges the influence many participants have on the outcome of a musical event and its subsequent capture. Every element including the composer, the players, the instruments, the acoustics, the atmosphere, the engineers and the audience affect the production throughout the process from initial moment of inspiration to mixing, mastering and even consumption itself. For our session, the Miraverse was in full effect.

The Band

We’d go in, track for a day and mix for a day to put the studio through its paces. The band would be Strother’s: Todd Harlan (vocals), Jeff Vogel (guitars), Ron May (bass) and Strother (drums). Does that not sound like a rock band? They’re called the Verses, and they’ve been a band for years, some of them going as far back as high school. From the first rehearsal recording they sent me, I could hear their unspoken musical ease together, a feel that’s easy to lose once you go into what can be an artificial environment of the studio. People performing music together — at the same time! — to create that magic feel is perhaps Michael’s number-one wish.

I recently had such a positive experience tracking a band without the use of headphones (I can’t believe it took me 20 years to do that!), it became my goal the Verses to cut our basic track that way. Due to a series of series of coincidences and my desire to record a song that reflected the idea of a studio facility on a scale such as this being the fulfillment of a dream, it was decided we would record a cover of Cheap Trick’s “Dream Police.”

Session Load-In: The Space Is the Sound

The drive from Raleigh-Durham Airport to the studio took me across a lush countryside to an area of lakes near Pittsboro, North Carolina. When I arrived, the appropriately hidden-away studio stood glowing on its own with a strategically lit sharpness and newness relative to the woods and tall grasses around it. Strother was just loading in his drums when I arrived; what better way to first hear the main live room?

Manifold Studios is two buildings. In photos, the building does not appear that large from the outside. In person, it’s really big. We walked right past the Harrison Trion digital mixing suite on our right and entered the larger tracking building with the API Vision console, the large “music” room, multiple connected booths and isolation spaces.

L to R: Ron May, bass; Todd Harlan, vocals; Strother Bullins, drums; Jeff Vogel, guitars

Upon entering the large, flagship music room, the air itself just seemed in harmony. When you turn your awareness to it, you realize all rooms have a sense of air pressure created by their size, the quality of the materials and the reverb time. Manifold’s music room is 52 feet long, 31 feet wide and 24 feet tall and comprised of low-frequency-absorbing concrete (used structurally for the first time ever, according to Lachot), exotic and conventional woods and glass. It’s an inspiring visual atmosphere in every room, noted by the band throughout the session. The first time Strother hit his kick drum, I could have sworn it was mic’d up and going through a PA with subs. I have never heard low-frequency reinforcement — bottom end — like that in a studio. Next we heard Jeff’s raging 4×12; in the main room, it was stadium-huge. Ron’s TC Electronic double-stack bass rig sounded clear and booming from 20 feet back. Going with the everybody-playing-together-with-noheadphones concept, we set up at one end of the studio in Ian’s recommended spot for the drums and everybody cranked up together. The sound of this three-piece rock band in the room reminded me of a 500-seat theater with no one in the seats; it was amazing, but I knew I wouldn’t be able to get the drum room ambience I wanted. Eight-foot-tall gobos around the guitar amps helped, but it was clear we’d have to make a bigger adjustment.

Just to change my frame of reference, I suggested we move the kit to the large, live iso booth. When Strother played, I could imagine a tight but not dull drum sound, similar to the original Cheap Trick recording. Yet the big room was still calling. I couldn’t have come all this way to record the drums in the booth. A distinct feature of the opposite end of the main live room is an overhang about 7 feet up and 4 feet in depth. I suggested we try the kit under this ledge at the point of the triangle. Suddenly, the sound exploded; it had all the openness of the big room, but the pressure around the kit of the smaller space, reminiscent of the use of a drum umbrella or tent. Coincidentally, the two doors equally to the left and right of the kit opened to the Loggia, a concrete and glass room with concrete bathrooms on either side, and the official entryway to the studio. With the heavy doors propped partially open, I was blown away a second time by the sound; I had found my drum reverb chamber, isolated from the guitar and bass amplifiers in the main room. Strangely, the entire stereo image of the drum kit, from hat on the left to floor tom on the right was retained when listening from the center point of the Loggia. [Visit the link at the end of this article for a listen to drum stems. — Ed.]

That’s where the mics would go. We enhanced this isolation and increased the immediate sound pressure around the kit by lining up the tall gobos around the kit, creating a kind of drum funnel. I placed the guitar and bass amps on the opposite sides of the gobos so the guys could stand in front of their amps, rock out, and see and hear one another perfectly with no headphones. The ambient sound in the big room was dominated by the guitar: the perfect big guitar reverb for the track. [Guitar stems are also provided via our audio clip link — Ed.] The studio had already proved itself fully acoustically versatile, capable of delivering whatever we asked of it.

L to R: Strother Bullins, Jeff Vogel, Ron May, Michael Tiemann, Alex Oana, Ian Schreier, Todd Harlan.

Mic selection was straightforward. Manifold’s mic locker features standard new mics from AKG, Sennheiser, Shure, Royer, Coles, Schoeps and DPA. [See sidebar for the complete list of session mics — Ed.] We drafted a Millennia TD-1 (somewhat MacGyver-ishly) as a signal splitter in order to feed a second guitar amp. Both cabinets were mic’d with Royer R-122s, which I feel are smoother in the top and more accurate in the bottom than R-121s. Bass went direct; we tried a mic, but ended up liking the TC’s DI output combined with a straight tap off the instrument the best. This was the end of our first evening. Load in and setup were done; time to sleep and hang with the band.

Bed and Breakfast

Manifold is about 40 minutes from Raleigh-Durham Airport and I’m sure there are hotels around, but we got to stay in Michael’s B&B just down the gravel path. It’s called Windsong and now that I read the website, I get it, but the reveal was slow at first. Picture a rock band and their producer exploring every room in the house after the first night’s session in search of a boombox and a lighter. “Whoa, man, there’s a ballroom in here.” And, “Yup, there’s a huge deck.”

The deck is where we relaxed with single malt and the sound of cicadas, and the newly remodeled kitchen is where the espresso machine got us ready to go in the morning. To continue, Windsong can serve as a band flophouse (as we implemented it), residential accommodations for a 10-piece band like Ozomatli, or a retreat center with a yoga/dance studio.

Session Day 1

I had made my mic selection the night before, so after Michael made me an awesome double shot of espresso at the house, we headed down to the studio where he assisted me in setting up all the mics. Everything at Manifold is new — like 40 pristine mics stands of all shapes and sizes, including those over-engineered, highly effective large booms by Latch Lake.

Manifold’s main men: Michael Tiemann and Ian Schreier on the Loggia.

Just to limit my variables, I decided to use the API Vision 212 preamps for everything. They sound so great: clear, punchy rock ’n’ roll. I spent a while EQing the drums, tweaking drum tuning and moving the mics around, whereas the guitar sound came together in a few minutes firing the Royers straight at the center of the cones about five inches back.

As the band rehearsed we adjusted a few levels, but I made sure to roll Pro Tools the whole time without mentioning it. After a run-through, we tweaked the arrangement to the verse and the band ran it down once more while I recorded. There was something magic in it. The band said they were ready to lay it down, and I noted they probably already had it but they were welcome to beat it. Jeff, the guitarist, had a feeling I was tracking and he was right. There’s something that happens when the mind shifts its attention making room for the unconscious to take over, and it’s a thrill to participate in their capture. No headphones, no click — just a band playing together like they do in their rehearsals.

Strings

In the original version of “Dream Police,” a high string part provides a defining texture to the song. None of us played keyboard well enough to recreate it, so a week before the session, Strother enlisted the services of engineer, producer, composer Liz May of SoundLizzard Productions to coordinate a string quartet to reproduce the string parts. Schoeps went on the violins, an M149 on viola, a Coles 4038 on cello and a pair of DPAs on room. Mic preamps were Tube Tech and D.W. Fearn — our only departure from the API console pres. The players had been rehearsing in the lounge of the Harrison Mix Suite while we finished our basic track. For their overdubs, we had to use phones. They assembled in a semicircle just as they would in rehearsal, but in the middle of this huge, open main music room. The sound was open and larger than the four instruments themselves. [String quartet examples are also available via our audio clip link — Ed.] In some sections, we double-tracked and having been at the controls for about 12 hours, Ian bailed me out in the end, finishing the last important punches and edits.

Session Day 2: Guitar and Vocal Overdubs

Alex at the end of a world-class line of outboard gear in Studio A.

Jeff switched from Tele to Strat, but we kept everything else the same to double the main track and layer some harmonies. One of the key sounds of our final recording came from our approach to recording vocals. We started by layering multiple tracks of vocals in the Loggia space using a Schoeps microphone for vocalist Todd Harlan. The hard-surface reflections created a harmonically rich, exciting reverb that we balanced with dry signal simply by choosing the distance Todd sang from the mic. You cannot buy reverb that sounds that complex and real at any price. The victory of our backing vocals in the Loggia gave Todd a real comfort level in that space. When it came time for the verse lead vocals, we just set up a ‘57 next to an M149 in the doorway between the Loggia and the main room to capture a drier version of the vocal sound with a hint of reverb tail behind it. Guess which mic we chose as the sound for our lead vocal?

Mix

I had pretty much run out of time and was really tired by the time we finished vocals in the evening. Nevertheless, Ian was a trouper and stayed up with me until 3 in the morning while I got to know the killer API 225L compressors in the desk and got used to the excellent monitoring from ATC SCM25s and the Dynaudio M4 mains. Using Lachot’s soffit-mounted mains is one of the best studio mains monitoring experiences I’ve had, yet all monitors and rooms take time to learn (and time, I was out of). Again, Ian came to the rescue and updated, per my and the band’s feedback, the mix I had started on the console. [Hear the final mix via our aforementioned link, available at the end of this article — Ed.] He wisely printed stems of everything back into Pro Tools for future revisions.

Arranger Liz May conducts the string quartet. Clockwise from Liz is Haley Dreis, violin; Josh Weesner, violin; Susan Terry, viola; and Leah Gibson, cello. Photo courtesy of SoundLizzard Productions

The Environment

Manifold’s website advertises the facility’s carbon neutrality. I didn’t delve into this concern much, as many things worth doing, like flying across the country to visit a relative or the multi-chemical process to manufacture the supple casing of a Mogami cable come at a significant energy cost. From what I observed, certain construction materials and considerations have been made, but when I snooped around the grounds a bit, careful not to step on the persistent frogs or walk into the resourceful spider webs, I also observed a dozen large-tonnage cooling machines on their own slab behind their own low-frequency absorbing cinder block walls. Environmental conscientiousness is a worthy goal (and potential selling point), but no one cares if your studio is carbon-neutral if it doesn’t do a good job as a recording studio. However, they’ve worked out their carbon offsets (I’m picturing hectares of new saplings going into the ground somewhere), and it comes as a cherry on top.

Manifolds

In geometry, manifolds are a way of expressing complex, 3D structures via more relatable two-dimensional drawings and mathematics, even representing 11-dimensional string theory to 4-dimensional space-time. Before even the first sketch, I can just picture Wes floating the idea of “manifolds” and Michael just running with it. These two clearly fed off of one another’s curiosity. While Wes (a Chapel Hill, North Carolina resident) was on a visit to the studio, I overheard him anchoring his point to Michael with “All I’m saying, from a design perspective, this would be perfect…” That’s like a producer who’s trying to get his way in the session saying, “I just feel it best serves the song.” In the world of Manifold, the song is to the recording as perfect design is to the facility.

One of the most identifiable qualities of the buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright is the sense of the structure appearing of-the-land around it, inside and out. New buildings like Manifold can take time to melt into the landscape — greens you could putt on, cascading koi ponds, and beautifully stained concrete tiles insulate the two-building facility from the creeping marsh around it. Someone during the session observed Manifold stands like a new church in a clearing, in the woods. I like that analogy because Manifold is temple of acoustics and technology, and its pastors are Wes Lachot and Michael Tiemann.

Thank you, Michael for hosting us, for the espressos you made me, your amazing enthusiasm, and for the opportunity to have a blast creating in one of the finest recording studios in the world. Thank you, Ian for doing so many things as I would have done them without me needing to ask, and for great ears in finishing my mix (now our mix) when it was time for me to catch my plane back to L.A. It’s been fun telling friends and clients about my experience at Manifold, and I’ve been conscious of how I’ve described it in a nutshell. But now that I’ve reflected back on it via this article, it’s clearer than ever that Manifold must be one of the finest music-dedicated studios built in the world in the last decade.

While Manifold has already been used for quite a few recordings and mixes, the studio has yet to officially open at the time of this writing. There are a few small kinks to yet to iron out, nevertheless Michael was gracious enough to allow us to take the studio for a test drive. I had a hard time adjusting to the cool, ambient temperature required to keep the console at the ideal temperature. It makes me think of Steve Albini’s gear racks, which integrate air-conditioning outlets at the top, directly above the gear. “Cool the gear, not the people.”

The mind-boggling digital integration of the studio would have made some situations nearly impossible for me to troubleshoot on my own. But that’s Michael’s world, and he was always on hand to keep everything talking. What Manifold needs right now is its first scratch: a Coke spilled in the console, a mic tree knocked over, a big scratch across the floor. I think it will help Manifold cross over from most thoughtfully designed studio to most loved place to record. Perhaps you will be lucky enough to give them that.

Over the course of two days (plus setup, plus an all-nighter), the Miraverse manifested its effect at Manifold Studios, creating a finished recording that achieved a rare result: It exceeded my expectations.

Manifold Recording | manifoldrecording.com

Alex Oana is a recording engineer, producer and mixer who helps engineers, producers and musicians find the right gear through sales at Vintage King Audio.