Photo: Courtesy Dreamworks

Collateral, directed by three-time Academy Award nominee Michael Mann and starring Tom Cruise and Jamie Foxx, is a dark thriller with a psychological edge and an intense, tightly focused soundtrack. Nighttime Los Angeles sets the mood. The plot: A cab driver taken hostage by a hit man is forced to drive the killer as he makes his rounds, from hit to hit, during one night in L.A.

While Mann (Last of the Mohicans, Heat, Miami Vice) is recognized as a purveyor of strong visual style, his sonic style is equally well-developed.

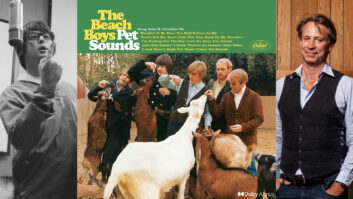

Michael Mann (left) and Elliott Koretz

Photo: Zak Koretz

“Michael’s like an athlete who doesn’t want to leave anything in the locker room,” says Collateral‘s supervising sound editor, Elliott Koretz, of Soundstorm. “Working with him is balls-to-the-wall high intensity all the time. He has a serious commitment to excellence and to finding uniqueness sonically and visually. In Collateral, there’s nothing superfluous. Down to the minutiae of helicopters in the backgrounds, every little sound and the frequency it occupies is important.”

While directors these days are often highly conversant about sound, it’s rare to find one who can actually discuss frequencies. Mann, a fixture on the dubbing stage, can definitely talk the talk. “He says that the most creative parts of the movie for him are writing and mixing,” Koretz says. “His seat is at the board between the mixers [Mike Minkler on dialog and music, Myron Nettinga on sound effects]. He watches what’s going on and occasionally says, ‘Roll off the low end,’ or, ‘Give me a little mids.’ He definitely gets it. He also understands a mixing console’s capabilities.”

Sound designer Elliott Koretz (left) and sound effect mixer Myron Nettinga at Todd AO West Studio 3

Collateral‘s sound is reality-based, with, according to Koretz, “not a lot of abstract design, except for a bit in the beginning where we introduce our characters. When we meet Tom Cruise, he’s walking through an airport. I designed some very diffused airport sounds where you get the feel of a lot of people, but it’s nonspecific, except for his footsteps. It stays that way until Cruise — seemingly accidentally — bumps into someone for what’s really a bag exchange. At that point, we snap to very real sounds where everything is sharp, clear and defined. So there’s some design, but for the most part, the movie is real sounds, well-thought-out to accompany what’s happening.”

With only two main characters, Collateral is sharp, focused and linear. It’s also very intimate. Everything happens in one night, most of it in one taxicab. “We used real sounds to manipulate emotions a bit,” explains Koretz. “After Cruise kills his first victim and Jamie Foxx has figured out what’s going on, Jamie becomes very upset. As he’s driving, we tried to come up with tension-filled sounds of the city.”

The Doppler of an alarm going off, the buzz of a light, people arguing, car speakers booming hard-core rap all contribute as the city becomes an element in the undercurrent of Foxx’s anxiety.

Collateral wasn’t spotted in the traditional sense, in which, prior to the start of cutting, all involved watched footage to decide where sound design was needed. Instead, early on, the sound team received a script to work from and spotted much later in the process. In another departure, Mann insisted on having his principal crew together in one location at his own Westside facility. “We didn’t work in our own offices,” says Koretz. “Everybody — the picture editor, the music editor, myself and my crew — moved to the Westside. It actually made for a lot of synergy. It brought the sound crew more into being a creative part of the whole process as opposed to being those ‘off-site sound guys.’

“I was able to look at cuts with the picture editor and discuss what would work sonically, and I was able to easily feed him sounds on a daily basis,” he continues. “Michael makes a lot of his critical decisions based on what’s in the Avid. So it was important for me to get my more-finished work to the picture editor and the Avid where Michael could hear the correct guns, the correct taxicab, et cetera. In the end, it made the transition from Avid to dub stage easier. It was also convenient that we were located just a few blocks from the stage so we could get together with the mixers to discuss strategy and how to lay things out.”

A hefty amount of fresh recording was done. “I got a lot of support from the associate producers and others in Michael’s organization to go out and get things I wanted,” comments Koretz. “We got a Metrolink commuter train, a big part of the end of the movie, to ourselves for an evening. That was great because it’s a fairly new system with a unique sound. Michael is also knowledgeable about guns and a stickler for their sound. So they lined me up with the on-set armorer, and we went to a private shooting range where we recorded six channels of guns.”

Field recordist Bruce Barris

Photo: Zak Koretz

For the Metrolink scenes, the team experimented with multiple setups and discovered that mics placed on either end of a subway car were optimum. “The distance from one rig to the other mimicked the distance from front to back in a theater,” says Koretz. “That gave us an incredible sense of movement as the train sped along.”

Shotguns, automatic machine guns, pistols and semiautomatic pistols were close-miked with Sennheiser MD421s, AKG D-112s, and Shure SM57s and SM7s. For distance, a mono shotgun Sennheiser MKH416 and a Neumann RSM 191 stereo condenser were used. Recording was to DAT: two Fostex PD2s and one Panasonic SV-255. “We set up to get the most variety,” explains Koretz. “We had extreme close-miking with mics set up behind us for echo and exterior slap. Back at the office, we synched up and mixed the channels on a ProControl to create either exterior or interior shots as needed.”

With something like 23 of them in the movie, cabs were a major component. According to Koretz, the main cab was recorded in six channels. “I’m a big fan of multichannel recording,” he comments, “because you can get the nuances of the surround information in there. Since the cab was such an important part of the movie, we recorded it any way we could: under the hood, in the tailpipe, in the front and back seats.”

Challenged to find Los Angeles night sounds that surpassed the stereotypical, Koretz and assistant editor Bruce Barris pulled all-nighters unearthing the unexpected, including, according to Koretz, “Guys steam-cleaning sidewalks at 2 a.m., a refrigerator starting up through an open window, laughter echoing down an alley and some very disturbing street people activity.”

The movie pays homage to L.A.’s multi-ethnicity. For one scene in a Korean nightclub, that meant actually getting recordings from Korea. “Michael was adamant about the walla being in Korean,” explains Koretz, “but the reality is that the younger generation all speak English. Ultimately, we hired someone in Korea who went to discos there and recorded the material.”

Collateral’s editorial and mix crew blow off some steam at a wrap lunch.

Koretz describes his crew as lean and mean. “I prefer to have a small crew that stays on as long as possible. I think that leads to more quality control and better communication. I can’t say enough about everybody who worked on this one. I’m the point man, but they do quite a bit of heavy lifting to make it all happen. And for this picture, my crew was definitely dwarfed by the music crew. [Laughs] James Newton Howard is the main composer, but there’s a variety of different music for different scenes from composers Tom Rothrock and Antonio Pinto to Paul Oakenfold and Audioslave. And there was an army of music editors.

“Although right now I’m a little tired,” he admits, “I feel that working with Michael has made me a better designer and supervisor. He challenges people and the end results have been movies that are unique works of visual and sonic art.”

Music By Many

Music supervisor Vicki Hiatt previously worked with director Michael Mann on Heat and Ali. “Michael brings a lot of people into the mix,” she comments. “For example, Brazilian composer Antonio Pinto, who did City of God, was — in ‘Michaelese’ — ‘the architect of Vincent’s [Tom Cruise’s character] deconstruction as it occurs throughout the course of the film.’ That’s not necessarily what he was hired for, but that’s what he wound up being. His music appears in reel 3, as the night starts to fall apart for Vincent, and it propels that dramatic line. James Newton Howard’s music is the emotional tension binding the diverse sensibilities that are the story of Collateral and Los Angeles.

“Tom Rothrock’s music wound up being Fanning’s story on some level. Fanning is the LAPD detective with intuition about what’s happening. Tom’s music is in the cue where we see Vincent for the first time, and also where we see Max cleaning up his cab and getting into it.”

Multiple music choices were available on the dubbing stage at all times. “Michael swaps the music in and out,” Hiatt continues. “But after he’s chosen a music cue, the picture changes. Our job is to keep the feeling intact even though the scene gets shorter or longer. That’s where the music editors really need to know what they’re doing. We were really lucky on this film; we had a lot of very skilled people.

“With Michael, it takes a lot of people and there’s a great deal of organization involved. It’s hard, but Michael puts in three times as much work as anyone else does, so it’s also very rewarding. And because his style is so painterly, it’s always visually stimulating. There’s never a dull day at work.”