Audio engineers today primarily associate the name Focusrite with high-quality audio interfaces and mic preamps, a reliable and musical means of getting audio into a computer via USB, Ethernet, FireWire or traditional analog. The range of the company’s products employ iPad control, Dante networking and most forward-looking technologies you can think of. But modern technologies don’t appear out of nowhere, and 25 years ago Focusrite was a much different company, emphasizing a much different product line.

In a sense, the Focusrite story parallels the changes in the recording industry as a whole. When Phil Dudderidge purchased the assets of Focusrite from Rupert Neve in 1989 (the company was founded by Neve in 1985), he inherited the legacy of the famed ISA 110 and 130 modules, along with the Forte console. After re-establishing production of the outboard line, he and a small group of engineers, led by Crispin Herrod Taylor (today of Crookwood), set about designing a streamlined version of the Forte, with a no-compromise, don’t-worry-about-cost-now commitment to quality. “It nearly bankrupt the company,” admits Dudderidge, with a sigh and a laugh, at the January NAMM premiere of the documentary film The Story of the Focusrite Studio Console.

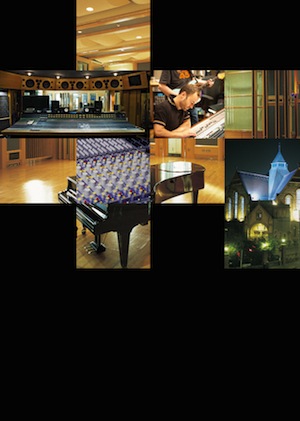

Only 10 Studio Consoles were ever made. The market had changed by the early 1990s, and eventually so would Focusrite. But the history of that console development forms the very basis of the company, so in order to celebrate 25 years in business, Dudderidge and his team went back and traced the path and story of each of the 10 consoles—to Ocean Way and Conway and SST in the States. To BOP Studios in South Africa and to a bedroom in Valencia, Spain. They went to four studios in Tokyo. The documentary was released last month in conjunction with a Dream Recording Weekend Contest at AIR Studios London, for which the original ISA 110 channel strips were designed, produced by Guy Massey.

“Everyone from the company was sitting around a table in the High Wycombe HQ in late 2012, discussing the idea of a ‘heritage project,’” recalls Chris Mayes-Wright, producer and director of the film and in global artist relations at the company. “We felt it would be a shame if the story of Focusrite’s rich heritage went untold and got forgotten. The concept of a video documentary following the 10 Studio Consoles was raised. It was decided that to do the story justice, we should tell the whole story of the consoles—why they were made, who bought them and why, and where they are today.”

The 10 very human stories form the framework of the film, and they are all rich and compelling, but in the beginning it was all about technology. Rob Jenkins was a recording engineer at the time and did some testing for DDA, another console company. He joined a core team of engineers at Focusrite in October 1989, six months into the development of the Studio Console. Today he is director of product strategy.

“We had two main objectives,” he says. “Minimize noise and distortion. The ISA 110 design is dominated by the input and output transformers. I spent a year recalculating the resistor values of each op amp stage in the channel strip to get the right balance between noise and distortion and heat. I then refined the mix bus system to improve the grounding and the hum cancellation. During the installation process I would tune out the mains hum of each mix bus until the noise floor was pure white noise. The net result was a quiet and pristine-sounding console.“

Throughout the film, studio owners and engineers express their passion for the consoles, and their sound. The trip to Botswana and BOP, through the South African veldt, feels almost out of time, while the insights from Jack Joseph Puig at Ocean Way bring some glamor. There is a touch of humor surrounding the current location of Number 6 in a bedroom of producer Victor Castellanos’ parent’s home in Valencia, and a bit of pathos and human spirit at SST Studios in Weehawken, N.J., where, nearly in real time, Mayes-Wright traces the destruction of a board in Hurricane Sandy and the hunt by owners John Hanti, David Hewitt and Billy Perez for replacement parts, eventually found in a garage in Austin, Texas, the remnants of the Conway Studios Studio Console. A bit of detective work. A great story.

“There was no script,” Mayes-Wright ways. “It’s impossible to script something like this with all the twists and turns. The idea was to make a film that everyone can enjoy, whether they’re into recording or not. The common themes we developed while shooting were: loss, hope, love, respect, evolution and rarity.”

“I’m really pleased that the concept of the obsession surrounding the consoles has been captured,” Jenkins adds. “There was a gang of us at Focusrite that for a few years in the early ‘90s literally did nothing but build and refine that console, it was a lifestyle. Now you see people like the guys in SST going through the same process again to keep the console alive. They have the same obsession. I look back on those days as the happiest in my professional life because of the people I worked with. I learned so much in that time. The console was my apprenticeship and my foundation in the industry and company I love.”