Fanise at work on his Nuendo system.

Serious gamers will be the first to tell you that not every great action movie can be successfully turned into a videogame. Indeed, for every successful film-to-game franchise — Star Wars has yielded many popular titles; Spider-Man, The Lord of the Rings and James Bond are also consistent winners — there are many more failures. Sometimes, it’s the animation that sinks a game; other times, it’s clumsy game play or an over-reliance on the original film’s plot and details, leaving too little room for the player’s imagination. Of the big fall 2005 film releases, the one that most critics agree made the smoothest transition to a game is Peter Jackson’s King Kong, made by Ubisoft. Reviews for the game, which actually came out a short while before the film, have been strong, and so have sales. It probably helped that Jackson actually collaborated on the game. But beyond that, who wouldn’t want to explore the creature-infested nooks and crannies of Skull Island or to play as Kong — fighting dinosaurs or wreaking havoc in 1930s New York? It’s an intoxicating adventure.

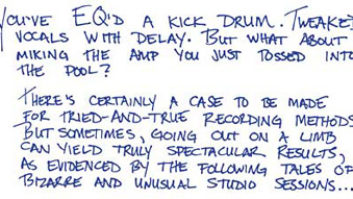

As with the heavily CGI’d film, the King Kong game is highly dependent on the quality of the animation and the realism and power of its sound effects. The game was made in Montpellier, France, by a large Ubisoft team; the sound effects, which already have earned the game a 2005 Best Sound Award from www.gamezone.com, were spearheaded by Yoan Fanise, who says, “Two years ago, Peter Jackson and his son played one of our previous games, Beyond Good & Evil, and he really enjoyed it — the story, the [artistic] realization, the deep emotions — so he contacted our creative boss, Michel Ancel, to make the game for King Kong. After several prototypes, he signed with Ubisoft for the game.”

Beyond Good & Evil, which took place on a planet populated by sinister aliens, was Fanise’s first experience creating videogame effects, but that was after many years as a sound editor and re-recording mixer for film and TV in France. “It was such a revelation to work with interactive audio for the first time,” he says, “despite the technical limitations of PlayStation2. Games are an incredible area to explore — there’s so much freedom of creativity.”

Yoan Fanise recording his Uncle Marc’s shotgun.

With some games made from films, the sound designers are provided with actual FX stems from the film, but in this case, Fanise says, “We had to finish the game before the movie mix had begun, and if you add time to re-edit, mix, integrate and de-bug sound effects in the game, it was impossible to get final sound effects from the movie. However, I did send my sound effects creations to them [Park Road Post in New Zealand] and they sent me some really great feedback, and later some stems from a temp [dub]. In the end, though, about 90 percent of the game sound effects are homemade, and that makes it sound different from the movie — it’s like another vision of the Skull Island atmosphere.”

To create the Skull Island ambiences, Fanise and his audio team spent several days in the mountains recording wind, trees, rock sounds and rivers with Fanise’s Tascam DA-P1 stereo DAT recorder and a stereo pair of Audio-Technica 4041 mics. “I also wanted to record lots of forest ‘silences’ — these really quiet backgrounds that make your atmospheres more immersive and realistic,” he says.

Like most effects designers, Fanise is constantly on the lookout for sounds: “For example, the rain in the sea storm in the first map of the game is a recording I made from the studio window on a day last year when there was flooding in Montpellier,” he says. “The authorities had forbidden everyone to take their cars into town, and [sound editor] Thomas Vannier and I were blocked in the studio, so we took the DAT out to record this heavy rain. It was perfect — no cars meant no traffic noise, and the big plane trees in front of the windows made the rain sound really tropical!

“Another great recording experience was the amazing collection of hunting weapons my uncle Marc has,” Fanise continues. “I could record all sorts of shotgun manipulations, as well as his new hunting bow that made really great arrow swooshes.” While Fanise stresses that most of the sounds in the game were original, he also used some FX library material from Sound Ideas, BBC and WWA (Wild World of Animals) with newly created sounds.

And, of course, one has to ask about the sound of the mighty Kong’s roar: “In the game, Kong’s roar is a mix of 12 elements, the main one being human — it’s a female horror scream pitched down a lot and saturated. It gives this tonal aspect that brings a strange emotion, a mix between sadness and anger. Peter [Jackson] described Kong as a really old monkey, alone for a long time on his island, so I wanted to add that aspect [of loneliness] to his basic angry roar. In the last month [of production], we received a temp version of Kong’s roars and sound editor Olivier Ranquet included them as an element of the edit. They have a really great presence.”

Fanise and his team did all of the FX and ambience mixing in Nuendo, “a total of 1,242 sessions for the 1,885 sound effects,” he says. “There are lots of reasons that pushed me to leave Pro Tools, and after two years of daily work with Nuendo, I won’t go back. Nuendo is so useful: You can combine 16-bit, 24-bit, stereo interleaved and 5.1 files without any conversion process, and there are also many little features that make your work more simple and fast.

“For the creature sounds, I used lots of plug-ins, principally the Delaydots Spectral Suite and the PSP MixPack [of analog sounds]. And for all the atmospheres sessions, I used the great freeware SIR [Super Impulse Reverb] convolution plug-in to re-create exterior acoustics. All of it was mixed in my DAW with my little [CM Labs] MotorMix [control surface].”

Fanise switched to Nuendo for its ease of use and flexibility in working with multiple file formats.

The time span from the first designs of the audio universe of Skull Island to the final mix was nearly two years, with the later mixing phases including making level adjustments in the FX to accommodate different game formats. “We had to tweak the reverb parameters for each [gaming] console, also set the 5.1 rules for the spatialization on the Xbox,” Fanise notes. “Also, the global mix volume is different on each console: The PS2 has great headroom and summing is not a problem, but on GameCube and Xbox, we had to lower the master [volume] to avoid clipping. But we had to use the same data for all platforms. I had no time to re-sample sound effects for each one.”

Who knows — if the game continues to sell well, then maybe Fanise and company will get to visit Skull Island again for a sequel, applying everything they learned from making this game, and creating sounds for new creatures and new worlds.

Blair Jackson is the senior editor of Mix.