In a challenging cultural landscape in which some symphonies have closed their doors and others have had to file for bankruptcy protection, the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, which rose from the ashes of the Denver Symphony when it closed in 1989, might point a way forward for others to emulate.

In 2014 alone, the CSO played at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival with Béla Fleck and played at Red Rocks twice, backing DeVotchKa and Pretty Lights, respectively. The CSO has also streamed audio in 5.1 at 128 kbps AAC+, and is looking at ways to video stream its performances.

While the CSO has traveled new avenues, it still performs the masterworks. In September 2014, the CSO, with Andrew Litton as conductor, recorded Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in 5.1 for a planned release on Blu-ray Audio in spring 2015. The project got its genesis from a conversation between Mike Pappas, who often records the CSO and serves on its board, and Wolfgang Fraissinet, the president of Neumann in Berlin. According to Litton, it was Fraissinet who suggested the Ninth.

“It was Neumann who chose to record our Beethoven 9,” Litton says. “They thought its huge dynamic range, visceral impact and brilliance would be a perfect demonstration of the excellence of their microphones. I had already programmed the Beethoven to open the season when they came along, so it was a happy confluence that brought us together.”

For producers, Pappas tapped Fraissinet and Leslie Ann Jones.

“Wolfgang was the real driver behind the recording project and wanted to co-produce it,” Pappas says. “He is a classically trained pianist who has a great ear, and the Beethoven was perfect for him. We needed a co-producer that could work well with Wolfgang, and on the top of that list was Leslie Ann Jones, who is the director of music recording and scoring at Skywalker Sound. Neumann Berlin had done several projects at Skywalker over the years, and Wolfgang had really enjoyed working with Leslie. My ulterior motive was to have a set of producers who understood the CSO’s desire to reach younger audiences.

“About 70 percent of people’s exposure to orchestral music is in movie theaters and video games, so they are going to be expecting something that sounds like a video game or film score, so you really want to have a set of producers that has a lot of that background,” he continues.

“I called Leslie Ann Jones up and asked if she would be interested in doing Beethoven’s Ninth and the Choral Fantasy as the co-producer with Wolfgang. I thought she would bring a different perspective to the project and work well with Wolfgang. As part of this, I focused on both a conventional stereo mix and a 5.1, because frankly, the future is in surround, and when you start looking at the penetration of home theaters, a large swath of America has home theaters.”

The core audio crew, from left: Chris Hansen, Julian Pichette, Alex Nemes, Leslie Ann Jones, Wolfgang Fraissinet, Robby Scharf, Blair Ashby, Kevin Giehl and Duke Marcos

PRE-PRODUCTION AND SETUP

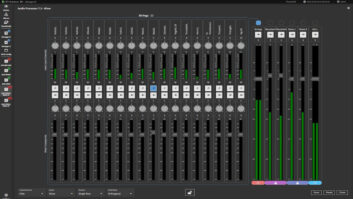

The recording was made in 24/96. Pappas’ existing recording console records at 48, so Fraissinet arranged with Stagetec to provide an Aurus Console from Germany that came with built-in AES42 support. Stagetec’s Alexander Nemes also came out to help New York City engineer Duke Markos learn the desk.

“It’s a very intuitive console that is laid out very much like an analog console, but because it’s a digital console, it’s extremely flexible and you have a lot of routing options,” said Markos. “We were very lucky to have Alex Nemes from Stagetec, who helped set it up and helped us work our way through the console. By the end of the project, I think I had a pretty good handle on it.”

Jones also liked the console, saying, “I had no previous experience with it, but I did find in my limited use that it was quite intuitive and certainly very flexible in terms of all the things that you can do with it. I was really quite amazed that in three days, Duke could handle it quite well. Once we got to the performances, anything I asked for in terms of what I wanted to hear or how I wanted to group things, we got worked out.”

The addition of the Stagetec console opened up new possibilities, and Pappas and Markos started looking at what else they could use the recording project for. To do the recording justice, the group decided on 66 inputs total, mostly with Neumann digital microphones, but also some Sennheiser digital microphones and Neumann analog mics.

“We started to look at the educational component of what we can do with this recording session to add a lot of value to folks in terms of understanding how mics behave in an orchestral recording environment,” said Pappas. “That meant we did things like double- and triple-mike certain instruments, like the first violin, which had a digital Neumann microphone, an analog Neumann mic, and a Sennheiser digital mic.

The control room, for recording: Robby Scharf, Wolfgang Fraissinet, Leslie Ann Jones, Mike Pappas and Duke Marcos at the Stagetec Aurus console (in foreground).

“That allows you to do comparisons, which is really interesting because the acoustic elements of both Neumanns are identical, and you had a digital body and an analog body on it, and you either used the AES42 input off the digital body or you went through the Stagetec TrueMatch microphone preamplifier on the console, which is a brilliantly designed piece of hardware. We did that on numerous instruments, so there’s a very nice array of multiple tracks where you can listen to the same instrument on three microphones incorporating different technologies.”

For his part, Markos felt that the AES42 integration on the Stagetec desk made the recording process a lot simpler.

“The integration in the console of AES42 allowed us to run the digital Neumann microphones and digital Sennheiser microphones in directly, and we were able to control all the parameters directly from the board. That is a huge advantage. I think it is really critical when using that many digital microphones to be able to control them like an analog mic right in the console.”

Jones is no stranger to microphone comparisons, and has done several for Neumann and Sennheiser in the past. But the sheer number of microphones affected her decision on the sample rate for the recording.

“I would say 95 percent of what I do is 24/96, so it’s not uncommon for me,” said Jones. “The choice was not going higher, because we had so many microphones. If it had just been the digital Neumann microphones, we could have gone at an even higher sampling rate, but given the Sennheiser digital mics and the analog mics, we had over 60 inputs. That meant that for us, going 24/96 on the recording and then mixing at 192 was the best choice.”

Between the orchestra and the chorus, setting up all the microphones proved challenging, and led to some interesting choices, such as putting shotgun microphones on the soloists. The compressed schedule for the project required an enormous amount of effort from many helpers, according to Pappas, who during the sessions seemed to be running everywhere.

“We had a very tight setup schedule, and the good news is we had a whole pile of volunteers coming in from all over to assist us in getting this organized,” explained Pappas. “We had a crew of four guys who spent six hours doing nothing but building the mic setups. We didn’t have enough mic stands, so the folks at Ultimate Support in Loveland loaned us a couple dozen at the last minute. All that stuff had to be figured out ahead of time, because we literally had three hours of time to set up, and that included building a Whirlwind snake, because we didn’t have enough snake inputs to get everything in. We had a front snake by the conductor’s platform that had 24 inputs, and we had another snake in back by the woodwinds that had 28, and then there was a bunch of stuff coming in from the grid, which is how we got to 66 inputs in one fell swoop. Whirlwind built us that snake and got it to us in four days after I realized we didn’t have enough ways to get it all to the stage racks.”

RECORDING

The recordings were made on consecutive evenings in late September at Denver’s Boettcher Hall, which is a challenging venue acoustically, and required some adaptation, according to Pappas.

“It’s got too much volume, the reverb time is about 3.5 seconds unloaded, and with a full house, you get down to about 2.75, which is a little long, even for classical music,” he said. “So from a miking standpoint, you have to do some things that you normally wouldn’t do. We typically tend to get pretty close. The main array is five Neumann KM 133 Ds, which is an M50 titanium capsule with a titanium diaphragm and a sphere. They are omnis that are flat to 2.5 Hz, but the sphere turns them into hypercardioids at 16 kHz. We use that to our advantage because we aim them into the orchestra to bring out presence without having to resort to using cardioids. The advantage of omnis is the spectacular low-frequency performance and transient response. We’ve got those relatively low at nine feet. We’d like to have them higher, but the problem is the room starts to get in the way of doing that.

“We put highlight mics on the first violin section, first desk, second desk, and third desk for this project. It’s the same thing with second violins, second desk, third desk. Violas have first desk and second desk. We did first and second desks of the celli. We always mike the basses because the room is a theater in the round, so there is nothing in the bass section to throw low frequencies anywhere you can use them. They have a tendency to go everywhere, and that means there is no real low-frequency texture. Those get a KM 133 D. In fact, we had a triplet in there, a KM 133 D and a KM 183 digital mic, and a Sennheiser MKH 8020 digital mic.

“We also had highlight microphones on the oboe and the principle flute. We put a couple of mics into the French horn section and brass. Additionally, we have the vocalists at front of the stage and they are way past the main array, so we used Neumann KMR 82 analog and KMR 82 D digital shotgun mics on them. Most all of those mics were in the mix at -10 dB to -22 dB or so. You don’t need much. It’s like adding cayenne pepper to a meal; a little goes a long way, and a lot gets you into trouble.

A close-up on the triple-mic setup: Sennheiser MKH 8020 with MZD8000 Neumann KM183D and KM133D

“Because of the reverb time in the hall, you need some highlight mics on the percussion section just to get a little transient snap. We used a stereo pair of KM 133s over the timpani section. Usually for normal work, I just put a single KM 133 D over the center of it, but Leslie wanted to do a left and right and get them in low. I have to tell you, I really like the sound of it. It was really nice, and was one of the things we stole from her and are doing for the rest of our symphony sessions.”

Fraissinet, Jones and Markos recorded the rehearsal sessions over the three days leading up the first actual live performance in case the producers needed to substitute things in for parts of the actual performance. Jones and Litton also had listening sessions each afternoon to go over aspects of the rehearsals, which was amazing to see, according to Pappas.

“Andrew would come in every day and do a minimum hour-long listening session of the previous rehearsal,” said Pappas. “He would listen with scores out and make copious notes of areas to fix. He spent one whole rehearsal working with the woodwind section and getting the intonation perfect.

“The way we miked this all, using the digital microphones, there’s so much resolution, there’s no place to hide. Everything has to be perfect, and Leslie was a monster about, ‘That note’s wrong, this has to get changed, the intonation sags here, this went ba-bump when it’s supposed to go bump.’ [She was also] working with Andrew, who was on top of his game in terms of getting it and writing his notes down, then working with the orchestra to make sure it was perfect, and the orchestra rose to the occasion. The orchestra wants to survive in the 21st century, and the only way to do that is to have the absolute best product you can.”

For their part, both Litton and Jones found working together to be an enjoyable and rewarding experience.

“It was great to get to know her,” said Litton. “We had a meal or two together first before we really got into the project, and that helps to build the trust that is essential between conductor and producer. You literally have to be on the same wavelength and there has to be a bond of trust. We established that immediately, and the work side of the project was a total pleasure as a result.”

Added Jones, “The conductor is really in control of everything. Andrew brings everything to the table, the performance, how he conducts, what he wants in terms of the particular recording, etc. Beethoven’s Ninth has been recorded umpteen times, but I really felt that he added a lot of emotion to his interpretation of the work, and really brought that out in the orchestra.”

The recordings were made on two separate systems, and the output connectors had Pappas scrambling at the last minute to make everything work.

“We had two different recorders. Blair Ashby ran Pyramix, and then we ran a full Logic 10 system using the new RME USB 3.0 input box,” said Pappas. “Not only did you need to record all the mics, you needed a scratch 5.1 mix and a stereo mix. The new RME wanted a smattering of coax and optical, and we ran everything MADI, so one of our last-minute crises when everything showed up is that we didn’t have the right optical adapters between the Stagetec interface box and the RME box. I was calling the telco division of Graybar and running over about two hours before we needed to record to get the right optical adapters to make it all work.”

Jones adds, “Once we settled on the number of microphones, the sample rate, and using MADI, the best recorder solution was Pyramix. Blair was terrific to work with. He spec’d the system with help from Dennis Gaines and Merging Technologies and was the recordist. It was also the best for post-production, as my editor Mark Willsher uses Pyramix.

In the months after the recording, all four have listened to the raw mixes and been happy with what they’ve heard. A couple of weeks after the sessions, Pappas took raw stereo mixes down to the Rocky Mountain Audio Show and played them in the Jeff Rowland Design demo room, and says the listeners were amazed. In part, that is reflective of Pappas’ hopes to get recordings that are the audio equivalent of HDTV.

“Back when I started recording the Symphony in 2004, I’d do this with eight or nine microphones, M 150s in a typical Decca tree setup, with M 149s as flankers set on omni, and away we went. It was that big, diffuse London Decca recording sound, Zubin Mehta conducts the L.A. Philharmonic kind of a thing. About five or six years ago, I woke up with the horrible realization that people don’t listen to music that way anymore. Certainly with the widespread adoption of home theaters, your recordings better sound like a film score, and they better sound as good as a film score, and if it’s not, people are going to be like, ‘What is this?’

“So, I sold my M 150s, sold my M 149s and started a transition to using digital microphones, then started using more of them, and started to work on texture. How do the string textures sound? What do the woodwind textures sound like? Now we can start hearing that. I want that texture. I want it to be like watching high definition television. You watch golf on HDTV and you see every blade of grass; I want you to hear every string in the orchestra, hear every flute, every harp, every part of it. We have 80 musicians on stage; if you add up all the years they’ve been playing, it’s centuries of experience. I don’t want a single one of those people, who spent decades honing their craft, to get lost in my recording. I want every one of them to be presented to their fullest ability.”