Discover the secret history of Trade Mark of Quality, the first bootleg record label, which covertly released dozens of illegal albums by music’s biggest names throughout the first half of the 1970s. In Part 2, we dive into secrets of the TMQ studio and more; don’t miss Part 1: The First Bootleg Record.

Housed in a generic white cover with its name rubber-stamped on the front, the first bootleg record, Great White Wonder, appeared around L.A. in the summer of 1969 and quickly made a splash. The random collection of Bob Dylan outtakes and live recordings put some money in Carl and Pigman’s pockets, but it was the Rolling Stones’ fall tour that year that turned their experiment into an ongoing, covert business. Asked by a friend if they could make a record that would capture the Stones live, the pair recorded six West Coast concerts in November that year, with little to no subterfuge required.

“At the time, no one thought about anyone professionally recording a live concert from the audience—and they didn’t care,” says Ralph Sutherland, author of A Pig’s Tale, which recounts the bootleggers’ exploits. “The concerts were recorded from the producer’s seat using a long, handheld Sennheiser MKH 805 shotgun microphone and a portable Uher Report 4000 reel-to-reel tape recorder using 5-inch 3M/Scotch reels at 7.5 IPS in mono. From 1969 to the mid-Seventies, this was the same equipment used to record most of the live-in-concert TMQ albums that were not recorded by others or from outside source tapes. There was also a short-lived use of the miniature Nagra SN tape recorder, which used cassette tape in a reel-to-reel format; that was used for recording live performances and was more easily concealed than the larger Uher tape deck.”

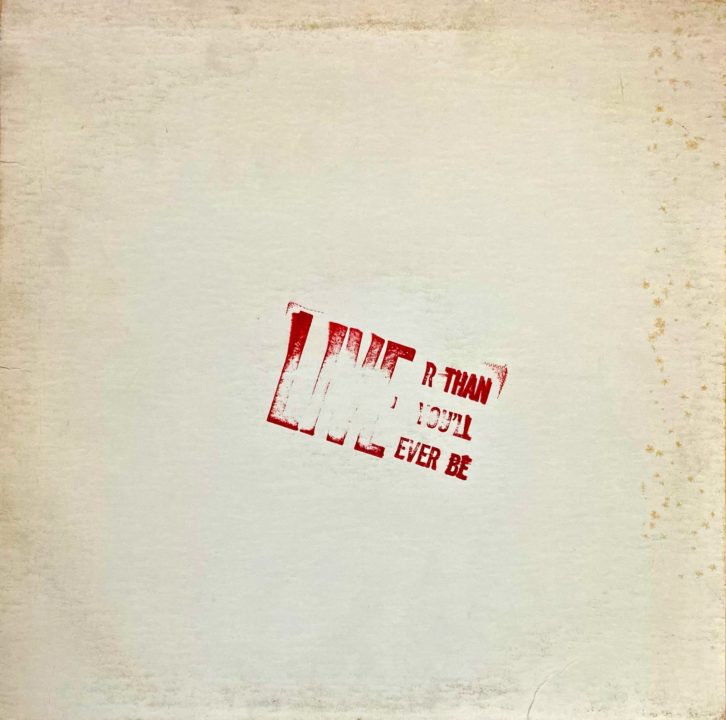

By the time the Oakland show was released as Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be and started getting national press, something unexpected was happening: The bootleggers were getting bootlegged, and grainy copies of their Dylan and Stones records were appearing in record shops. Despite that, ill-gained dollars continued to fill their pockets, so there was no question they’d make more records now—but if they were going to continue, the shady enterprise needed a name to distinguish itself from competitors: Trade Mark of Quality was chosen with tongue only partially in cheek. Since they were flush with cash, just like a legitimate startup might do, they decided to pour the profits back into the business and build their own studio.

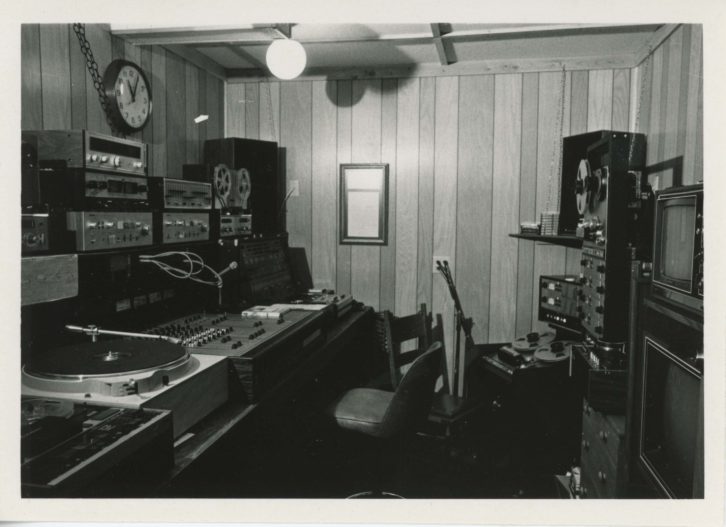

“The goal was to produce the finest quality bootleg records possible at the time,” says Sutherland. “The master tapes were made on professional studio Ampex machines, utilizing Dolby and, later, dbx noise reduction. Most of the tapes were made and edited on professional Ampex 10-inch reels at 15 IPS. There was one 1/4-inch two-track and one 1/2-inch four-track machine with an optional 1/2-inch 3-track playback head, a four-channel Tascam mixing board, equalizers, echo/reverb units, four JBL 4310 three-way studio monitors and two Yamaha stereo amps. This also made it possible to produce Quad/four-channel masters. There were also two additional Revox A77 tape decks and a transcription turntable which could accommodate any size or speed vinyl up to 16-inch transcription acetates, with various types of cartridges and stylus. The TMQ studio was state-of-the-art for its time and no expense was spared.”

The industrial turntable was indicative of TMQ’s growing range of bootleg sources, as radio transcription discs with in-studio performances were perfect for plundering. TV programs, too, served up ample bootleg fodder, so TMQ’s studio was outfitted with a broadcast-quality Ampex color video tape recorder with stereo audio.

“I was with them when they recorded a few things,” says co-author Harrold Sherrick, “like when they recorded the Jefferson Airplane Up Against The Wall bootleg, which was from two KCTV Channel 28 broadcasts; the audio was taken off them, which made for a great-sounding record.”

Initially a number of indie pressing plants around Los Angeles were used to manufacture the records, but the quality varied, since not everyone on the take was invested in superior sound. “Later in 1970, a pressing plant not far from L.A. International Airport was discovered,” says Sutherland. “Most of the TMQ albums into the mid-Seventies were pressed there; the pressing quality improved and was much more consistent.”

CLICK FOR PART 3: Changing with the times, fooling Led Zeppelin and the end of the road for TMQ.

A Pig’s Tale is available from Genius Books and tmqapigstale.com.