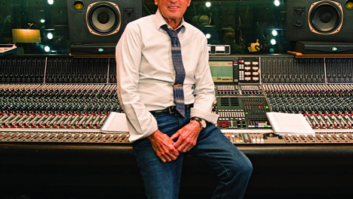

This month Hal Leonard Books releases legendary engineer/producer Al Schmitt’s autobiography, and it’s been a long time coming. Still working at age 88, out of his longtime home base at Capitol Studio A, Schmitt has engineered and produced more than 150 Gold and Platinum records, earned 23 Grammy Awards, and left an indelible imprint on both the recording industry and the music industry at large. He should have had at least a few autobiographies by now. Then again, he’s not the type of guy to talk about himself all that much.

It was Schmitt’s confidence in “co-author” Maureen Droney to tell his story right that brought the project to life. Droney, Mix’s former Los Angeles editor and a fine engineer in her own right, having cut her teeth at San Francisco’s famed Automatt in the 1970s under the tutelage of producer David Rubinson, is now the Recording Academy’s Managing Director of the Producers and Engineers Wing. She’s also managed House of Blues Studios and East Iris Studios, and authored Mix Masters: Platinum Engineers Share Their Secrets for Success, and co-authored The Pensado Papers, about the rise of the audio industry web phenomenon Pensado’s Place. She knows her way around a studio, and she knows the industry.

Still, it took a little more than three years of interviews, background research, and the usual back-and-forth that comes when piecing together an individual’s lifetime story to reach the final mix. The time paid off, as Al Schmitt on the Record: The Magic Behind the Music is a loving portrait of an incredibly talented and humble man. In the telling, Schmitt comes across as warm, humble and blessed, a man seemingly unaware of his Mount Rushmore status in in the history of audio recording, while at the same time a man sure of himself, comfortable in the presence of genius and knowing that he belongs in the room.

The book begins with an amazing anecdote of the 19-year-old Schmitt, freshly home from the Navy, showing up for his shift at Apex Recording Studios on West 57 Street in Manhattan, the Steinway Building, and unexpectedly finds himself alone behind the board for a Duke Ellington big band session. Without spoiling the story, because it’s a good one, Schmitt pulled out his small notebook where he wrote down the setups shown to him by his mentor, the late, great Tommy Dowd, and he ended up doing all right. At one point, Schmitt recalls, after letting everyone know there had been a mistake and he was only allowed to do “little things,” Mr. Ellington said to him, “Don’t worry, son. The setup looks fine, and the musicians are out there.”

The New York section that follows is a treasure. Schmitt maintains vivid memories of his childhood in Brooklyn during the Depression. It is recalled as a simple home life—honest values, a good work ethic, but no real money to go around. He played pranks, worked for nickels early on to buy his zoot suits (he has always liked to look sharp, and he still does), and by the age of 8 became enamored of his Uncle Harry Smith, an engineer who opened Harry Smith Recording at 2 West 46th Street in the 1930s and did very well. Lot of jazz sessions, lots of big bands. It’s where Schmitt learned the vibe and etiquette of the studio.

He met countless musicians, became a lifelong friend of Les Paul, learned to cut records to acetate disc, and developed a taste for the big band sound. They were simple mic setups back in the day because they had limited channels. Schmitt learned to let the players play, a philosophy he maintains to this day. He’s known for moving a mic a quarter-inch rather than adding EQ, and he still keeps setups simple.

Then he met Tommy Dowd at Apex and his world changed. Audio experiments were an everyday event. Transcription recordings. Disc to disc editing. Drive from the studio to the radio station. All of it was part of the birth of the modern recording industry. Schmitt was 19.

He met Ahmet Ertigun, and work with Atlantic Records followed. He went on to Fulton Recording. He was there at the birth of stereo. And then Los Angeles beckoned. In 1958, Schmitt landed at Radio Recorders at 7000 Santa Monica Boulevard, the most happening place in town. He worked with Connie Francis, met Bones Howe, and was behind the board for Henry Mancini at he height of his powers. Sinatra, Streisand, Natalie Cole, Diana Krall. The list is long.

RCA followed, then independent producing, back to engineering. There’s an especially fine section where Schmitt recalls flying up to the San Francisco Bay Area to produce Jefferson Airplane at the height of flower power. I’ll let you read it for yourself.

The autobiography is equal parts an insight into Schmitt’s recording philosophies and techniques. He talks as easily of the particulars of ribbon mics and cutting acetates, or how he likes to mike flutes, as he does of the personalities out in the studio. His techniques seem so simple when he explains them on paper. But nobody else can get that sound. He’s worked with so many of the greats; here we learn what makes Schmitt so great

A reader gets the sense that this is what Al Schmitt is all about. Just a kid from Brooklyn who loves to be in the room making music. A kid who loves the sound of a big band when it’s swingin’, a rock band when it’s roaring or a vocalist when she’s completely in the moment. The magic behind the music.