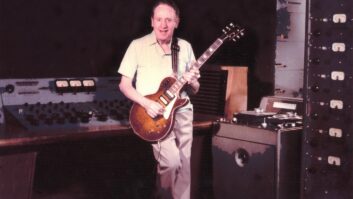

This week, Hal Leonard Books releases In the Studio with Michael Jackson, in which five-time Grammy Award winning engineer Bruce Swedien documents his work with Jackson and legendary producer/arranger Quincy Jones in shaping the sounds of the King of Pop’s solo albums, beginning with 1979’s Off the Wall, and including Thriller, Bad, Dangerous, HIStory and Invincible. Swedien was plucked from a job at Bill Putnam’s Universal Recording Studios in Chicago, where he met Jones in 1958, when he began working with Jones and Jackson on the 1978 soundtrack to the movie version of The Wiz.

The new book focuses on the creative and technical aspects of Jackson’s studio productions and offers more than 100 photos, including many of Jackson at work in the studio, as well as other artists and collaborators. It also has photos of the studios and equipment used for Jackson’s sessions, plus scores of Jackson’s handwritten notes and other never-before-seen ephemera.

The timing of the book’s publication is noteworthy in that it arrives one month after Jackson’s passing on June 25, 2009, during a time of renewed public interest in the entertainer’s life and career. However, Swedien and Hal Leonard Books emphasize that In the Studio with Michael Jackson has been in the works for several years; Mix magazine first mentioned this book in the November 2008 issue (“Q&A: Bruce Swedien,” available at mixonline.com).

“I imagine there will be people that will say that I’m an opportunist and wrote the book for Michael’s untimely death, and I did not,” Swedien told Mix by phone from his home in Ocala, Fla. “I’ve been working on the book for several years, and it’s all about my work with Michael. The response has been incredible. I had no idea there were that many people interested in what we had done—but they are interested!”

“Though the book was in production for many years we did not anticipate its release coinciding with the events of the last few weeks,” states Aaron Lefkove of Hal Leonard Books. “As engineer, Swedien was, along with producer Quincy Jones, one of the creative partners and architects of Jackson’s sound. The book is part anecdotal memoir, part technical reference, and paints a vivid portrayal of Michael Jackson as an artist.”

I asked Swedien for his thoughts about In the Studio with Michael Jackson, and he graciously shared some memories of his work with Jones and Jackson.

Why did you decide to write this book? How did it come about?

Well, it seems like Quincy and Michael and myself changed the shape of popular music in history, and so I figured I would address the technical part of it and exclusively to my work with Michael, which I have done. And I’m a funny guy: I don’t believe in secrets. I’m going to tell everything in this book—how I did every sound in as much detail as I can.

There’s certainly a lot to be said about the working chemistry between you, Quincy and Michael.

Oh, it was the greatest, absolutely the greatest, and I have tried to say as much as I can about Quincy as well—that I respect him and love him. We’ve worked together since 1958, and Quincy is the greatest, and his musical depth is legendary. I mean, he studied composition and orchestration with [French composer/conductor/educator] Nadia Boulanger. I think you could say she mentored Quincy, because to hear him talk about her just gives you the chills. The depth of Quincy’s knowledge of music is second to none.

The real deal is when we were recording the overture for The Wiz in New York. It was a huge orchestra, 70 or 80 pieces, and we were recording it in Studio A1 at A&R Studios in New York. This must have been 1977 or something like that. Quincy and I were living together in an apartment in the Drake Hotel on Park Avenue. I had one bedroom and Quincy had the other, and then the suite shared a dining room and a kitchen. So we were set to record the overture for The Wiz—big orchestration and everything—and it was on a Sunday that this event took place. Monday was the day for the session with the big orchestra. They were going to start at 2 p.m., and it was the opening titles for the movie. So Sunday, Quincy hadn’t put a note on the paper. We talked about it and everything, and I was starting to get a little nervous. Of course, I had worked with him for so long that I didn’t get all that nervous, but I knew that he had something in mind, but nothing on paper yet. Sunday we had some friends over for dinner—I think Billy Eckstine was there, and a bunch of really important people. We were having a great time and still, Quincy hadn’t put a note on the paper. So the people had left and it was midnight or 1 in the morning, and I said, “Quincy, what are we going to do? We’ve got this huge orchestra coming, and you haven’t written anything for the opening titles yet.” And he says, “Don’t worry about it.”

Recording the orchestra for The Wiz.

So Quincy was up all night working on this thing, and at about 4 in the morning I woke up and noticed the light blasting in under my door, so I crack open my door and looked at Quincy, and there he is at the dining room table, [which is] covered with manuscript paper, and he’s working like a dog. There were no musical instruments in our apartment—no piano, no guitar—nothing but the instrument between Quincy’s ears.

Quincy didn’t sleep at all that night; he was writing, he was up the whole night and got it. We get in a cab and go to the studio—big, beautiful studio. We get there, Quincy’s carrying sheets of music with him and we had an army of copyists ready to go. Quincy did not conduct the orchestra; he hired a conductor because he wanted to be in the control room with me listening to the mix. So we’re working away on this overture to The Wiz and Quincy had never heard it in actuality. The orchestra played it down, it was about five or six minutes long—not one note put of place! Now to me that’s unique. This piece of music went to tape moments after it went on paper. True story. It’s part of working with Quincy Jones.

Then your collaboration with Quincy and Michael began in earnest the following year with Off the Wall.

I think that was Michael’s coming-of-age musical statement because it is much more mature and musically very deep.

I have a technique that I’ve been using for many years where I have a plywood drum platform that I use to get the drums up off the floor. The reason for wanting to get the drums up off the floor is to minimize what you call secondary pickup. If you don’t get the drums off the floor, the low sounds—from the kick drum and toms and so on—will couple to the floor and they’ll spread, and end up having a huge impact in the other microphones in the studio. So by building a heavy-duty drum platform eight-feet-square and about 8 inches off the floor—heavily braced and with the surface not painted or varnished in any way, so that it’s porous and there’s a little bit of sonic absorbency to that—really works.

And after I used that platform for the drums, I got to thinking about it, and I used that same platform to record Michael on, because he dances when he sings, and I didn’t want to lose those sounds and lose the impact of his dancing sounds. And I’m not a purist; I’m not the kind of a guy that, with an artist like Michael Jackson, wants to have his vocals pristine and pure. I think that would be rather boring because there’s a lot of “street” in what Michael does, and I figured it would be best to use this drum platform and reflect those dancing sounds back to the microphone, and it works out really well. Then I hooked up with my pal Arthur Knox of Acoustic Sciences, who introduced me to TubeTraps, which I use then to go on that platform around not only the drums, but later when Michael was singing, I’d put the TubeTraps around Michael on the drum platform.

I have never recorded Michael Jackson where he sang a lead vocal with the lyrics in front of him. He always stayed up the night before and had the lyrics committed to memory, which is kind of interesting, and I challenge the young pop stars today to duplicate that. I don’t think so. But Michael could.

Your book offers a valuable historical document and interesting stories to the music industry.

I don’t think people have realized how serious Michael was about the musical part of it, and he was indeed. “Serious” is a mild expression—he had a passion for the music. I’ve worked with major forces in the music industry and I think Michael was perhaps the top of the heap there, and I just figured I’d be remiss if I didn’t say something about it in detail. How could you not? To be in such an important place as that was, at that point in music, I had to tell this story.

Matt Gallagher is Mix’s assistant editor.