Seventeen years between albums is an eternity in the pop music world, yet half a minute into the first track on Blondie’s greatly anticipated reunion album, No Exit, it feels as if the group never left. The hard ska beat, the aggressive guitar, the wheedling, semi-cheesy keyboard and the distinctively smooth vocal of Deborah Harry announce that the band are intent on picking up where they left off. The famously eclectic group still refuses to be pigeonholed: No Exit contains invigorating slices of driving pop (“Maria,” “Nothing Is Real but the Girl,” “Under the Gun”); the Bach-meets-metal hip hop-inspired title track (featuring rapper Coolio); a slick but still trashy girl-group cover (the Shangri-Las’ “Out in the Streets”); dreamy ballads (“Double Take,” “Night Wind Sent”); a cajun-style waltz, complete with sawing fiddle (“The Dream’s Lost on Me”); a smokey hep-cat jazz tune (“Boom Boom in the Zoom Zoom Room”); and, to end the album, a mesmerizing bit of aural voodoo that sounds like it might have been written by Dr. John (“Dig Up the Conjo”). All in all, it’s quite a pastiche of styles, but still unmistakably Blondie.

“Blondie is the epitome of what a pop group is supposed to be,” comments Craig Leon, who recorded and produced No Exit some 20 years after he helped produce their debut, which remains one of the great works of the early new wave period. “They do what they want, and it still sounds like them. They never stood still long enough to be boxed into one style.”

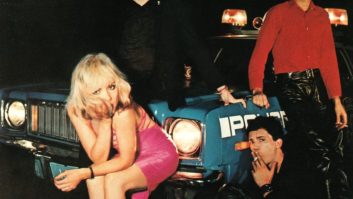

The Blondie reunion includes four members from the old days-Harry, guitarist Chris Stein, keyboardist Jimmy Destri and the incomparable drummer Clem Burke. A host of other musicians-most notably bassist Leigh Fox and guitarist Paul Carbonara-fill out the sound on the album. The songwriting duties were shared by the group members and a few outsiders, such as Romy Ashby and former Go Go Kathy Valentine. So far, the album and promotional tour have been received warmly, especially in England, where Blondie has always had a huge and rabid following. In fact, the first single there, “Maria,” entered the UK charts at Number One. Three live cuts recorded on their fall ’98 UK tour appear as powerhouse bonus tracks on No Exit: “Dreaming,” “Call Me” and “Rapture.” The album was cut at Stein’s home studio, at Electric Lady and at Chung King, all in Manhattan, with Leon engineering. Leon mixed eight tracks at Abbey Road in London (where he has lived since 1986); the remaining six were mixed at Encore Studios in L.A. by Mike Shipley. The live tracks were recorded by James Birtwistle in the BBC Live Music Mobile and mixed by Randy Nicklaus.

In early March, I talked to Debbie Harry, Chris Stein and Craig Leon about the making of No Exit, about Blondie’s earlier work with Platinum producer Mike Chapman, and about what the future may hold for this still-creative and endearing band.

How did you hook up with Craig Leon again? Twenty-two years has to be one of the longest gaps between records for a band and producer. Debbie Harry: When we were tossing around ideas and his name came up, it just seemed natural. Here was a guy who worked well with us in the past, and since then he’s done a lot of interesting, chancy stuff. So we figured, if we’re having a reunion, we might as well have a real reunion.

Chris Stein: He’s really diverse, and that’s part of what we liked about him. He’s done classical and rock and folk and Prodigy and all this other stuff. He’s very open-minded and into experimentation, like we are. He’s really a very far-out guy, very futuristic and a modern thinker.

Jimmy and Clem had worked with him in the interim, and then when I talked to him, he said all the right stuff. We had a long conversation, and it seemed like everything he said about how we should approach the project made sense; we were on the same page.

Craig Leon: I’d worked with Clem on a couple of projects in England, including some successful pop records-with Mark Owens and a solo album by Steve Hogarth from Marillion. But I’ve stayed in touch a bit with all of them through the years, and every once in a while various members of the band would say, “You know, one of these days we’re going to go back in and do it like it was in the old days, when Chris had a loft in the Bowery and we’d work up a few songs and go in and cut ’em.” This has been going on for years-I’d hear it maybe once or twice a year. But this time there was a management company involved, and I started getting calls from everyone saying it was happening.

Originally there was a different vision for it. I believe it was going to be a greatest hits package plus a few new tracks. Mike Chapman was going to do a track or two, and I’d do a track or two and even somebody else might do a track or two, covering the spectrum of the different sounds of the band, and something radically different. Then that kind of fell by the wayside so we figured we’d start working on something to see what we could get, to see if we could come up with any tracks at all. And it just evolved over time into sorting through a lot of tracks and turning it into an album.

Did you have a vision of the production going into the record? It’s more stripped-down than a lot of the later Blondie records.

Harry: That’s definitely a big difference. We worked it up bit by bit and made decisions as we went, but I, for one, had done three solo records that weren’t as thick, and I think it was a natural way for us to go.

Stein: Another thing Craig brought to the record that I really liked was a certain minimalism. The old stuff is very dense, wall-of-sound with layered guitars and lots of doubling and all that, and by comparison this is a very minimal record; the most like our first album in terms of the technique. I guess there are a couple of doubled vocals, but not much, and I don’t think there are any doubled guitars at all this time.

What is Red Night Recording, where some of the album was cut?

Stein: That’s my basement studio. I have an old MCI console, and we brought in an 02R and the Otari RADAR and some older outboard mic pre’s, nothing too extensive. We demo’d the whole record with drums here, with just a few microphones, and did basic tracks. We’d do these basics where we’d have the song finished in a day or two. We also did overdubs and everything here in the house on a demo version.

Harry: With the RADAR we got to demo the whole album and get a sense of the flow of the record. We got to listen to basically a scratch version of the whole thing, and then we redid it.

Stein: We went to Electric Lady and redid the basic tracks with bass, guitar, drums in their rooms, which have such a nice sound. In some cases, we redid the other instruments, in some cases not. Then we came back here to my studio and did a lot of overdubbing and refining. Then, toward the very end we went over to Chung King and did some work there.

Leon: Basically, I showed up with my own equipment that I’ve been using here in Britain. Blondie is the ultimate band that works in sound bites and very short loops. Even when they were doing things analog back in the old days, they were doing things in loops, but live. So now we have a really good piece of digital equipment that I use a lot, the Otari RADAR, which became my master recorder on it. And that enables you to do sequences of human live base material, so I thought it would be ideal for them.

Harry: I think we did it smartly. Chris’ studio is not the most comfortable place, but we certainly had a more relaxed atmosphere and the clock wasn’t running, so to speak. It was a place we were used to; we’ve all done things there over the years. And with someone like Craig doing it all digitally, it was a really good way for us to work everything up quickly and to know which way were going with it, and, frankly, to save some money. This was the first record we’d done digitally.

What were the original demos like?

Harry: Most of them were just music. To me, demos are usually just musical ideas; brief outlines, sketches. I know that these days record labels like to hear a close-to-finished piece before they even consider using a song, but we’ve never worked that way. We’re sort of old-fashioned in that we really like to go in and develop things as a group, taking our time. Someone like Chris might come in with a really firm idea on a melody line or chord changes and a feel and bass lines and so on. But then when we actually get to doing them, they evolve with the input of everyone. Or sometimes they don’t evolve; it depends.

Leon: The way Blondie works is the lyrics and vocal lines come last, so everything is done pretty much in terms of tracks first. When I came to New York in February of last year, some of the songs were in really great shape and some of them weren’t. Some of them evolved from being little sketches into being something else. They weren’t demo’d in any organized fashion. I’d heard various tapes of all different kinds of ideas, but I think there was only one song, “Under the Gun,” which is one they’d tried with Mike Chapman years ago-that was pretty together. But even that mutated into something totally different. They had an incredible amount of musical ideas, particularly Chris and Jimmy.

What would happen is they’d start with keyboards and a guide click. We actually rehearsed the band in Chris’ basement, and I recorded that live to the RADAR and we found all the tempos and all the arrangements. We worked up the songs live, and I chopped them around a lot in the RADAR to get the structures right. You might have a 22-minute jam, and then we’d turn the best bits of that into something. Rather than doing it with analog takes in the studio and cutting it together, we arranged it all first and then went down to Electric Lady and cut the final arrangments to the click tracks we’d done at Chris’ studio.

So at Electric Lady we did the bass and drums to the guide keyboard and click, loaded all that back into the RADAR, chose the best takes from Electric Lady, and then I’d put together what could loosely be called Take One and Take Two from about 20 takes. And then Take One or Two would be what we put in the RADAR as the version. We’d get the basic track we really liked edited all together in the digital domain, and then to get the sound of tape compression, which you can’t get any other way, I’d send it over to a Studer [multitrack]. Then we transferred it back to the RADAR later to work on overdubs.

Stein: The RADAR is capable of putting very inspired performances down because if something is a little out time-wise, you can fix it. Plus you can do all the cut-and-paste, so if you get a really great guitar part, you don’t have to play it a hundred times; you can move it around and have the same part for every verse if that’s what you want.

Is there a sense when you’re working up material that a certain kind of song or sound is “Blondie”?

Harry: When you get us together in a room, we sort of become Blondie, if you know what I mean. So that wasn’t really an issue. But we wanted it to be eclectic and a little strange. We tried to have a lot of variety.

Stein: I just always hear Debbie in my head, and then I hear Clem’s style; that’s pretty much how that works. Jimmy would probably tell you the same thing.

I always thought Clem was the great underrated drummer of the new wave era.

Stein: He’s a spectacular performer. He has a tendency to get emotional about his playing and will speed up at the high point of the song, which sometimes drives the bass player crazy, but it doesn’t bother me much.

Leon: Clem Burke is one of the best drummers ever. They’re all better players now, of course. And actually the one who’s grown the most is Debbie. She’s had the experience of working with the Jazz Passengers and various other outside projects, and she’s seriously pro. She was always there giving her opinions. But her specialty is taking a vibey track and then coming up with an incredible vocal line on top of it. Sometimes she’d iron that out with Chris, sometimes with Jimmy. It depends on who wrote the basic core of the song.

Did you mike Clem’s drums any differently than you had 20 years ago?

Leon: It’s almost identical. Clem likes to go for the classic British sound.

Well, he was the new wave’s answer to Keith Moon.

Leon: He was! So we miked him the way we would usually do here at Abbey Road. And we used the standard Electric Lady big drum sound, which I guess goes back to Eddie Kramer. And that is basically a lot of room: two 87s at about floor level; a 47 on the kick, believe it or not-that’s an old British technique-and then a Beyer 88 on the snare and a 451 on the bottom; and 421s around the toms and a C24 overhead.

The first couple of Blondie records had this sort of live punk aesthetic, and then Mike Chapman came in…

Stein: Right. The first two records were made the way most people make records, which is you go in and you play like a band and you do a few overdubs and that’s it. Then, when we got to Chapman, it was like school’s out; we really spent a lot of time on the records we made with him.

How did that relationship come about?

Stein: He came around to see us at the Whisky [in L.A.], and he liked us a lot and he seemed to “get” what we were doing. Phil Spector came to see us and wanted to produce us. That was in one of his manic periods. We went to his house one night, and he was waving a .45 around. Anyway, that relationship never went anywhere.

I remember when I was writing for BAM in the late ’70s we had Chapman on the cover dressed as General Patton, at his insistence.

Harry: Exactly! He knew himself. He had a good sense of humor about himself.

Stein: Yep, that was him all right. He was amazing, though. At one point he had something like three different Number One hits three weeks in a row, with us and “Hot Child in the City” [Nick Gilder] and something else. He had something like 40 Number One records; it’s insane!

So his autocratic style didn’t bother you?

Stein: No, because he never tried to write for us. He just tried to pull the best performances out of us. For me, he was a total influence in production and just general musicianship and learning about being patient and the value of repetition. Because in any artform, you have to repeat yourself, and it’s always a challenge to do something a hundred times and to make the hundredth time as fresh as the first.

Harry: He was pretty much of a dictator, but he had all this credibility as the popmeister-the tunemeister-and we learned a lot from him working on those records. Even though they were considered very “pop” by some poeple, they were still pretty adventurous.

Obviously it was a good enough relationship that you kept it going for several records.

Harry: Oh yeah, he’s a really charming guy. Even though he worked us pretty hard, we still had a lot of fun. He was always cracking jokes, and every once in a while he’d whip out a bottle of tequila or something for us. He knew how to make records, and he liked working with bands. He’s the kind of producer who worked well with bands.

You guys did a one-off with Giorgio Moroder for “Call Me.”

Stein: Moroder was like the exact opposite of Chapman. He didn’t want to do hard work at all. A lot of what’s on that record are parts that he replaced. They’re parts that we played and then he just replaced them with his guys rather than having us bother refining them.

Harry: He had done a lot of nice things. The soundtrack for Midnight Express; and I loved the Donna Summer track he did; that was beautiful. He was a totally different kind of producer than Mike Chapman. He was really in control of what came out on the final record. We would go in and each of us would play parts that we liked, and then he would have them completely redone, incorporating some of those ideas. It was more like the producer-as-creator, which is not the way we were used to working. He’s not really a “band” producer.

Blondie was one of the first new wave bands to cross over into dance music, and I recall it being quite controversial at the time because there was a real breech between the two camps.

Harry: That’s right. We took some shit for it. A lot of our contemporaries were very put off by that and shocked and so on, but I didn’t really see the difference in a way. It was our take on that thing, and it certainly didn’t sound like everything else that was coming out in the dance clubs. It sounded like us, and it had a more aggressive feeling and more guitar action in it. Looking back, it seems silly that anyone was shocked by it, but they were.

Stein: Those dance songs were so much more difficult to make than regular rock ‘n’ roll! If you did a song like “Heart of Glass” today, with MIDI, if you could come up with the parts, you could put that together in a few hours. But at the time we made it, it took us something like two weeks. It was all manual, all played around one little synthesizer pulse track and a rhythm machine part. The bass drum took like three hours-Chapman insisted that every single beat had to be exactly right. The guitar part was done with tape delay and it took hours and hours, making sure the pulse of that was perfect.

Harry: You can’t imagine how hard it was to do that mechanical feel and be so precise, manually. It really was a labor-intensive record. That’s the way Mike worked; actually it’s the way most people worked in those days. He was a real precise person, and he liked everything to sound very clean. We worked really hard for him, and I think it paid off.

Leon: He brought them into the realm of competitive commercial disco, and things like that, and that wasn’t my forte at the time, to say the least. I’ve since grown to really like dance music and have done a lot of things in it, from Jesus Jones to hardcore techno stuff like Super 2.

When you work with a producer, be it Chapman or Leon, do you tend to be very vocal about your own ideas?

Stein: I’m not afraid to speak my mind. But I’m also open to other people’s ideas. You have to be to be in a band. That’s what a band is if it’s working right. Craig and I were very close on this project [No Exit].

Harry: It depends on the project; it depends on the song. On some things I know exactly what it should be, and on other things I listen to other people’s ideas and judgments more. With the earlier Blondie records, I really didn’t want to be involved in production decisions. At this point, with the more minimal approach, I find it more to my own sensibilities and I tend to have clearer ideas about what I’m after.

You worked with Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards on Koo-Koo, Debbie’s first solo album. What can you say about their production style?

Stein: They weren’t as rigid as Chapman. They tried to be, but they didn’t quite get there. Later, I tried to remix one of those tracks, and I was amazed at how much Tony Thompson’s rate of speed changed even though I thought it was so solid at the time. I couldn’t sync it up with anything.

Harry: Oh God, that was hysterical! They were very funny. It was a good collaboration. It came out about six months before “Ebony and Ivory,” and at that time I don’t think Chrysalis really wanted me to break off from Blondie; they really wanted Blondie to continue, so they really didn’t push it very much, and they didn’t make much of the fact that it was a collaboration between black artists and white artists, which at that time wasn’t done very much. The fact that it was Chic and Blondie I think was kind of brilliant. I’m very proud of that record.

On the new album, is a song like “Dig Up the Conjo” pretty much the way it was conceived, or did it evolve as it was recorded?

Stein: That evolved. Jimmy had something he did on the Kurzweil as the basic track, and then we threw the guitars on it. You know what it is? It’s like the groove for that Beatles song, “Tomorrow Never Knows” [off Revolver]. That’s what we were thinking of. Then the vocal melody changed it a bit, gave it that Eastern feeling.

I really like the layered vocals. Were those parts preconceived or did they appear as the song developed?

Harry: It started with just the lead vocal, and then I wanted to try something unusual to make it sound more eerie. So that’s what the harmonies do. In spite of its dark side, there is a certain levity about that song.

Leon: I like that song a lot. It’s sort of psychedelic. Clem wanted to to do something with a British psychdedelic feel, so that’s what that turned into a bit. Jimmy had the original concept for it, but Clem came in with the groove.

Was “The Dream’s Lost on Me” conceived as a cajun country tune?

Stein: Yeah. That was a song I did a demo for on one of those little Roland pocket sequencers. Clem had been talking about doing a 3/4 song, and I had it already sketched out. At this point we’re thinking of doing a more straight-ahead country-rock version because no one ever crosses over into country from rock; it’s always the other direction.

Harry: Chris had wanted to do a waltz piece. That’s one that’s pretty much the way he brought it to us.

“Out in the Streets” is a nice slice of girl-group pop, with those cool backing vocals.

Harry: That’s a song Ellie Greenwich [and Jeff Barry] wrote for the Shangri-La’s. Ellie has worked with us through the years. We thought it was sort of apropos today because of all the gang stuff going on. But it’s such a beautiful piece of music. It’s actually a song that Blondie has been doing since 1974. I’ve been doing that song for a long, long time.

Leon: “Out in the Streets” was the first demo I ever heard from Blondie, when I was working at Sire way before I got involved with them.

For the backup vocals on the album, we’d usually fit those in after the lead vocal was done. Sometimes we’d leave gaps for them. There were also some parts that were done on keyboards originally that were taken off and replaced with vocal lines. There was a lot of chopping and changing all the way to the end, including replacing some of the basics.

What’s the story with “Boom Boom in the Zoom Zoom Room”? Debbie, was that influenced by your work with the Jazz Passengers?

Harry: Clem came in with this idea that we should do a little swing thing; he was thinking about the Jazz Passengers. The lyric was from a story that Ronnie Catrone told me; it’s just a crazy thing.

Leon: We were going for a sort of murky, kind of lounge-y sound that was almost like a cross between something on an old Doors record and jazz, and even elements of the first Suicide album I did-that’s partially what Clem was looking for with the strange hi-hat thing going in the background. So that’s what the track was, and then Debbie came up with an incredible jazz melody on top of it.

Does being on the road with Blondie feel nostalgic, or does it feel like a new thing?

Harry: It’s a little of both. We know each other so well and yet this is definitely a new era for us, a fresh start. A lot of our old friends and fans are showing up, which is great, and also teenagers-kids who never saw us years ago.

Stein: It’s really mixed. It’s great-I’m meeting a lot of young girls! [Laughs]

Can you play obscure Blondie tunes or do you feel an obligation to pretty much play the hits?

Stein: We pretty much stick to the crowd-pleasers. A few years ago, I wouldn’t have wanted to do that, but now I’m seeing everything through fresh eyes and so it doesn’t bother me. There are so many young kids out there who have never seen us perform before, so it’s nice to be able to play the songs they might know. I’m even feeling kind of sentimental about some of the old stuff myself. We’re playing four songs from the new album right now; we’ll probably work up seven or eight before it’s over.

Harry: I enjoy playing our hits. They’re all pretty good songs. They’ve enriched my life, and there’s a certain personal satisfaction you get from that kind of acceptance. People love these songs. We’re entertainers. I’m happy to sing them. “Rapture” is a lot of fun to do. “Dreaming.” I like them all. Obviously, there is a lot of other material we could do, and on my solo tours I did some Blondie songs that were a little more obscure, like “Cautious Lip” and “Rifle Range,” and I enjoyed doing those.

Do you see No Exit as the first in a series of new Blondie albums?

Harry: One would hope so, but honestly I guess it depends on business. If the record sells, it will warrant us doing another. I’d like to do another one, try some different things. Maybe we’ll do something that’s a little more unusual next time; I really can’t say what it will be. Maybe we’ll do something like Metal Machine Music [Lou Reed’s infamously unlistenable noise record]. Who knows?

Leon: I really hope they do another record. From what we’ve been talking about, it’ll probably be something that’s radically surprising. This record [No Exit] is to establish that, yes, Blondie is still in existence and they can still sing and play great. But the next one…well, we’ve discussed all kinds of things. It could be pretty out there. I hope so! [Laughs]