As a “glamour profession,” the recording industry is full of people whose names and faces are familiar to the general public. Yet for the last half-century the course of the recording industry has been greatly influenced, if not entirely guided, by a handful of businesspeople and entrepreneurs whose names and faces rarely appear in the media. Some, like John Hammond, Clive Davis and Mo Ostin, directed the growth of existing record labels, while others, such as Ahmet Ertegun, Jac Holzman and David Geffen, started their own. Among this elite group must also be numbered Chris Blackwell, who not only founded and managed a record company that has been producing hit records over four decades, but has also branched out successfully into film production, hotel management and recording studio ownership.

Born in London in 1937, Blackwell spent his childhood in Jamaica, where his mother’s family had been successful in the rum, sugar, coconut and cattle trades. Sent back to England at age 10 to finish his education, Blackwell returned to Jamaica in 1955 and held a variety of jobs, including selling real estate, renting motor scooters and acting as aide-de-camp to the Governor of Jamaica. However, when he heard an ensemble led by blind pianist Lance Hayward at the Half Moon Hotel in Montego Bay, Blackwell decided to record them and, borrowing the name from Alec Waugh’s novel, Island in the Sun, founded Island Records.

In 1960, Island Records opened an office in Kingston, Jamaica, and a series of local hit singles soon followed. The growing Jamaican immigrant population in England also bought Island’s discs and, finding that he was selling more records in England than in Jamaica, Blackwell moved Island’s headquarters to London in 1962. A succession of minor hits followed, mainly ska records from the seminal Jamaican producers of the time, including Duke Reid, Leslie Kong and Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd, and within a few years Blackwell had produced or licensed several hundred singles for Island and its various subsidiary labels in Jamaica and Britain. In 1964, Blackwell produced “My Boy Lollipop” by a 15-year-old Jamaican girl named Millie, and it became the worldwide hit that launched Island’s global fortunes, selling more than 7 million copies. (Aware of his independent label’s limitations, Blackwell licensed the record to Fontana Records to ensure wider exposure and distribution.)

Accompanying Millie to a TV show in Birmingham, England, Blackwell discovered a local R&B quartet that included the 15-year-old Steve Winwood. Blackwell signed them immediately, and licensed the renamed Spencer Davis Group’s records through Fontana to get the mainstream pop exposure then still beyond the scope of Island. After modest success with covers of blues and R&B tunes, Blackwell introduced the group to Jamaican singer/songwriter Wilfred “Jackie” Edwards, whose “Keep on Running,” provided SDG’s first Number One record in the UK. The Spencer Davis Group subsequently had two international hits with “Gimme Some Lovin'” and “I’m a Man” and, when the group broke up, Island was now ready to handle Winwood’s new group-Traffic.

Throughout the ’70s, Island Records introduced the world to scores of critically acclaimed artists, and the UK and U.S. album charts were continuously re-stocked with records from Island and its licensees (U.S. distribution was typically licensed to other companies). In addition to Traffic and Winwood, Island formed the launching pad for the recording careers of Free, Cat Stevens, Spooky Tooth, Robert Palmer and Mott the Hoople, and also distributed Chrysalis and E.G. Records (Jethro Tull, Procol Harum, King Crimson, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, Eno, etc.). The winning streak continued into the ’80s and ’90s, and artists whose significant releases appear on the Island label include Grace Jones, Ultravox, U2, Tom Waits, The Orb and Pulp.

But perhaps Blackwell’s most lasting influence on modern popular music resulted from his Jamaican roots and familiarity with the Caribbean musical heritage. Starting with The Wailers’ innovative Catch a Fire album (which featured a Zippo lighter-shaped album cover), Island Records introduced the world at large to Bob Marley and reggae music. Artists such as Toots and the Maytals, Burning Spear, Third World and Black Uhuru not only added a multicultural component to pop music but also had lasting influence on Island Records labelmates and recording artists worldwide. Blackwell was also the first major label executive to expose African musicians, including King Sunny Ade, to a wider audience.

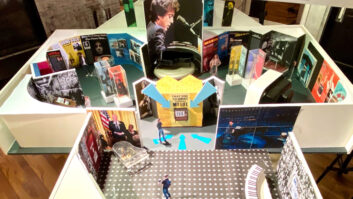

Although he downplays his personal involvement in production and engineering, Blackwell was a hands-on executive for a significant number of Island’s records. But if his role as a producer in the studio is not easily defined, his influence on final product is clear. Early in the 1970s, Blackwell foresaw that the LP would replace singles as the primary format. Even as he gave Island’s artists unprecedented creative freedom to develop their music, Blackwell also encouraged innovative graphics and album cover design. The company both upended traditional notions of packaging and spearheaded a new sense of style in cover design, as a glance through any coffee-table compilation of album cover art will confirm.

Island and Blackwell also have a long history in film and film sound. Blackwell backed his first film project in 1971, The Harder They Come, starring singer Jimmy Cliff. In 1981, he produced Countryman, which broke all Jamaican box office records. In 1983, Blackwell formed Island Alive, the film production and distribution company responsible for Kiss of the Spiderwoman, which won a Best Actor Oscar for William Hurt, and The Trip to Bountiful, for which Geraldine Page earned a Best Actress Oscar. Island films Mona Lisa and Dark Eyes also garnered Best Actor nominations for Bob Hoskins and Marcello Mastroianni, respectively. Other Island-produced films in the 1980s were A Night in the Life of Jimmy Reardon (starring River Phoenix), Choose Me and Return Engagement (featuring Timothy Leary and G. Gordon Liddy).

In 1989, Island was bought by Netherlands-based conglomerate PolyGram, although Blackwell stayed on to supervise the Island companies. Separately, in the early ’90s, Blackwell created Island Outpost, a hotels and resorts company, and debuted in November 1991 the renowned Marlin Hotel in Miami’s South Beach (which also houses one of Blackwell’s two remaining studio ventures). Blackwell’s vision of opening unique hotels and resorts in exquisite locations has since expanded to include six Island Outpost hotels in South Beach and six resorts in the Caribbean.

Blackwell continued his interest in the music business, and during his stewardship of Island under PolyGram, the label continued to develop hit artists, including Ireland’s The Cranberries. And in 1995, Blackwell formed Island Black Music, a music division created to sign and promote R&B, soul, gospel and hip hop. Signings have included new acts such as Dru Hill, and Island Black Music has revived the career of the legendary Isley Brothers, whose label debut sold more than a million copies.

In November 1997, Blackwell parted ways with PolyGram’s Island Entertainment Group and also left PolyGram’s management board (two years later, PolyGram itself was sold to Seagram’s scion Edgar Bronfman Jr.). In 1998, Blackwell started Islandlife, a new umbrella company that united Island Outpost with a new entertainment venture, Palm Pictures. With Palm Pictures, Blackwell returned to his roots in the entertainment world, releasing innovative music and films theatrically and on DVD, CD-ROM, CD and home video. He has also created a Web site, Islandlife.com, to link all of the Islandlife companies. Islandlife is the parent company for other Blackwell ventures as well, including Manga Entertainment Inc., a company designed to market and release music and visual material on the new DVD format and cutting-edge Japanese and international animation films.

At 62, it’s fair to say that Chris Blackwell seems to be just getting started. He certainly didn’t lose any momentum for this interview-it was staged over a cell phone on five separate occasions in at least as many cities.

You were already making records in Jamaica, but was meeting Miles Davis in New York in 1959 an epiphany for you?

I met Miles through Sid Shore, a songwriter. He wrote “Evil Spelled Backwards Is Live” and other great songs recorded by Eartha Kitt, Lena Horne and other jazz artists. I met [Miles] at Birdland, and it was a high point to me at that time. I was meeting a hero of mine. It was an incredible experience. I met the whole band. Sid and I were the only white guys backstage. At the time it was odd for a white kid to be hanging around blacks. But it was something I was comfortable with, coming from Kingston. I guess that’s what differentiated me, and Miles took a liking to me and let me hang around. It was like going to the best college or university you could possibly go to for what I had already decided I was going to do with my life, which was music.

What attracted you about Miles Davis?

He was a complete rebel. Everyone else would come onstage and chat with the audience and be very show biz. But Miles just played. He never talked to the audience.

I loved jazz, and I loved music. But I was not into pop music. I was a kid-almost, anyway-and when a kid likes something he gets enthusiastic about it. That’s how I was about music. It was a way to get your ideas across. I was into every part of it. I was always very much into album sleeves and reading them.

How did you learn about producing and engineering records?

I learned by sitting with different people and watching and listening. In Jamaica at that time, there were very simple [recording] facilities. We made records in a radio station in Kingston. It was a primitive facility-primitive in terms of the equipment, not in terms of the building or the acoustics. But that’s where we made Lance Hayward at the Half Moon.

What was available to you in Kingston at the time?

There was JBC-the Jamaica Broadcasting Company studios-and Federal Studios. The engineer there for that first record was Ken Khouri, who was the first person to have a pressing plant in Jamaica and who also repped Columbia and RCA in Kingston. There really was no music center in Kingston at the time, except for calypso music, which was for the tourists. When I left there in 1962, the stuff on the charts-there was Mario Lanza and Billy Vaughn, incredibly middle-of-the-road stuff.

The record that gave you your first hit was “My Boy Lollipop” by the Jamaican singer you discovered, Millie. Where was that recorded, and where did that striking reverb come from that sounded so good on the radio?

We made that record in 1964, and it was released in November of that year. We recorded it at Olympic Studios in London, when it was at the Carlton Street address. It was recorded by a staff engineer there. I was interested in engineering. I found that if you could learn how to get the sounds, you could get them quicker. That’s why I always wanted to work with the best engineers-to get at the things that are in your head more quickly. Back then, an engineer was an engineer, and a producer-usually an A&R person-was the producer. As a producer, you wanted to try this or that sound, and you told the engineer, and he moved a knob. It was frustrating. The producer brought in the artists and the song, but it was the engineer’s responsibility to get the sound. It was a time of making records when you hoped no one dropped anything in the last ten seconds of the take. I never really considered myself an engineer, but I did have an ability to get a good sound and to mix.

On that record, the reverb came from a sort of cupboard in the back of the studio that we used as a live chamber. It was a mono record, and we fed the sound in, adding a bit more of the reverb on Millie’s voice. The record worked well for radio, but partly because it was a minute and 51 seconds. That was important for people at radio who were putting playlists together. Also, Millie’s voice was irresistible-for a certain length of time, anyway. So a short record worked well for her.

You found the Spencer Davis Group-with their B-3 player and vocalist Steve Winwood-at a show you accompanied Millie to in Birmingham. What was your involvement with their records?

I produced some of their records-all of them except “I’m a Man” and what became the hit version of “Gimme Some Lovin’.” Jimmy Miller had added some backing vocals and remixed it, and that was what was the hit. My involvement in the actual production varied from time to time. The B-3 sound came from Winwood himself. My production was trying to catch the essence of their energy onstage. We set them up as an ensemble in the studio-Olympic again-and just baffled them off a bit. There were no real overdubs except for the occasional solo. I never did things like pick microphones or place them. We weren’t breaking any rules at that time when it came to making records; they were quite straightforward. But there was a new generation of engineers coming up then, people like Glyn Johns and his brother and Eddie Kramer. They started as straight engineers, but they learned to listen differently.

You figured out that the album was rapidly replacing singles as the primary vehicle in the 1970s, and Island also paid meticulous attention to design, transforming the traditional notions of packaging and style. You were starting to sign artists based on the depth of their artistic vision rather than their capacity to generate single hits.

My vision was always albums. I love a hit as much as anyone, but I really like records of artists, because that to me is what you hear in jazz records. The album was the difference between one song and a career. What I looked for was deep-rooted talent. The ability to be intuitive. Not because the lyrics or attitude was great, but lots of little things that can be exciting about artists or projects. But it also had to be something I really liked. A producer should start off by producing what they really like, because the chances are better with that than with anything else.

Did you remain as hands-on as a producer as you had been earlier? Or were you being pulled away from it by the business?

Some years I’ve been very much in studio and others not at all. It’s gone in waves. From the time we started Island Studios on Basing Street, I remember I was in the studio a good amount, between 1968 and 1977. Island Studios was near Portobello Road; it’s now SARM West. It was quite an amazing studio: It did Who’s Next, Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix. I produced Free there, although we did them at a lot of studios, like Trident Studios off Wardour Street [in Soho]. Jimmy Miller did the first two Traffic albums, and I produced John Barleycorn and The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys.

We used the studio to work out ideas, which is why I liked having my own studio. I could work with the band and make comments as it was happening. There were still very few overdubs for those records. Maybe Steve Winwood overdubbed his parts or the solos on a separate track. I had creative input into the record-making process, but I would say that I was more of a channeler. I was not the auteur type of producer. I felt my role was to help someone reach their goal. When I felt close to understanding what they were trying to achieve, that’s when we were successful in the studio.

The period you describe was the germination period for a lot of rock’s classic producers. Did you feel a part of that?

I didn’t interact with other producers. We were generating our own group of producers and engineers, guys like Miller and Steve Lillywhite, who started as engineers for us and then whom we made producers. Guy Stevens was a journalist, a DJ who I hired to head A&R for Island’s R&B label, Sue Records-he produced Mott the Hoople. He created Procol Harum.

A lot of great producers made records for Island. What were you looking for in producers?

Someone who really brought out the most out of a project, who made the best record for the artist. I wanted to think long-term as well as short-term. Even if there was a song that might have been hot, I didn’t want to damage the long-term credibility of the artist.

There were some artists that have the heat, but do a fast burn, though. Frankie Goes to Hollywood falls into that category. Trevor Horn made a great record that first record. He made a great second one, too. But it was the first one that got the attention. Frankie had a great voice and a great attitude, things I look for in the long-term. This one turned out to be an exception to the sorts of artists and projects I associated myself with. But I can get excited about an individual project vs. a long-term development thing. You need projects of that sort-big though not necessarily long-term-to give the record company credibility, to make it easier for your sales and marketing people to do their work projecting the label. There has to be some instant gratification involved. This is the record business. [Short, dry laugh.]

You’ve had a long history in film. You kept Island on the cutting edge in terms of album graphics; Island was a strong early supporter of music videos-Robert Palmer’s “Addicted To Love” helped drive MTV in its early years. Did you think in terms of visuals when you considered or worked with an artist in the studio?

Absolutely. Grace Jones had an incredibly powerful presence. She worked with [visual and staging designer] Jean Paul Goude, who was a graphics and production genius. For her first record, I had an idea of the sound I wanted: a kind of harsh sound that was heavy with Jamaican rhythm and then her on top of that, rather stridently. The picture, the image, was important. In the studio, I put up a 5-by-5 blowup of the album cover, pasted to the studio wall, before we started recording-her with her crew cut sitting with her arms crossed in black and white. Very powerful image. I said to her, “We need to make a record that sounds like that.”

You decided upon the album cover and image before you recorded the first note of music?

Yes. I work from a very visual point of view.

What was it about U2 that made you sign them? A number of other major record labels had already passed on the band.

I didn’t instigate the signing of U2. Rob Partridge, head of publicity, gets credit for that. I went to see them in London in July 1980, and I loved them. I loved the band’s name-names are important to me. They had already found Steve Lillywhite as their producer. I wasn’t really involved in their career except to the extent that I gave an edict to give them maximum support.

You stuck with artists like Winwood and Robert Palmer, who didn’t have career hits until a few years later in the ’80s. As a producer or executive producer, how did you guide their creative careers in the interim? Do you ever really stop acting as a producer?

You never really stop, even when you’re not in the studio with them. In the case of Winwood, he is a musical genius, very gifted. But it was a shaky course after Traffic. He made some uncertain records, to say the least. So I was supportive. How could you not be with such a talent? The problem, as I saw it, was that it was hard to get him to meet and see new people, to create a stimulus creatively and do new things. It was when he met [lyricist] Will Jennings and hooked up with him that a real match was made. Will wrote lyrics that Steve could relate to.

Robert [Palmer] and I became really close friends. Robert was unique in that he was so interested in other types of music and was not afraid to cover it. A lot of people since The Beatles felt that they should only do their own songs. On his records, he would do five or six outside songs as well as three or four of his own.

Palmer’s last record was heavily Caribbean-influenced, even years after working directly with you. Did your own Caribbean roots affect artists deeply?

The whole dynamic of coming from Jamaica had at least a tiny influence to most of the artists. They were exposed to music they otherwise would not have been.

In the early ’70s, you went back to your Caribbean roots and brought out Bob Marley & the Wailers and, in doing so, brought reggae into the pop music mainstream. How did you change the sound to make it palatable to pop while still keeping its fundamental integrity? How did you adapt reggae’s organicness to an increasingly high-tech recording world?

It really happened by coincidence. Jimmy Cliff left Island, and I was quite disappointed. The movie (The Harder They Come) had just come out, and I thought we could break him globally. A week later, Bob Marley walked into my office, and my feeling was that we could take the same character as Jimmy and bring him to life through Bob. Bob was the real thing. I encouraged Bob to make an album, not a single. [According to a VH-1 biography on Peter Tosh, Blackwell “challenged” Marley to make the album for $7,000. Blackwell responded that it wasn’t a challenge: “I simply offered him 4,000 pounds to do the record, so that’s about right.”]

We did a lot of post-production on that record, editing the songs, shortening them, extending them, taking out vocals, adding guitars. Bob was involved in that process; he didn’t expect it to be so extensive when he went in, but then neither did I. But I felt that by massaging the tracks afterwards we could make a record that would reach a wider audience.

Up till that time, reggae was considered novelty music, and it thought in terms of singles only. The whole process of that first record was to present Bob and the Wailers as a band, a black rock band. It was meant to jump over the predisposition that reggae was not serious music. There’s always a system you have to face when it comes to new music.

A system?

Yes. A system of people, not the music makers, but the people who have to sell the records and get them on the radio-promotion and distribution and retail. The creative people and the people in the art department were into it immediately. But the system is slower to accept new things.

Aside from Compass Point and South Beach Recording, what other recording studios have you owned? Was it a business you liked in and of itself, or were studios a tool for the larger vision?

We had the little one in back of Island Records at 47 British Grove in London. I don’t like studios as a business at all. I had and still do have them, because I’m in the record business. I don’t think you can be in the record business without an affiliation with a studio.

Studios are part of the creative process, yet they are like the club business-it’s all machinery and real estate. What makes them work or not work is their spirit, and that comes and goes. The spirit right now is very good at Compass Point. Terry [Manning, producer and studio manager] and his wife Sherry are fantastic. The studio had an incredible surge when it first started, then it lost direction. Now it’s back on track. South Beach is the same thing: [Studio manager and producer Joe] Galdo is fantastic at his job. I intend to keep both places running. There may be a new one in Jamaica at some point.

But it’s hard to figure out what the future of the studio in general is right now. What value does it bring to the business? It used to be that you could only make records in a recording studio. Now, it can be done anywhere and often is.

You’ve been making films for more than two decades now. What are your feelings about the way films sound-music and dialog and effects-then and now?

I had no feeling either way at the time I started making them. Films were mainly in mono back then, but I was very interested in mixing them in stereo, to get a wider spectrum of sound.

On the subject of soundtracks, I think often that the soundtracks are simply overdubbed into the film to make the soundtrack record and not really thought of as integral to the film. That’s certainly not the way I make music for pictures. One of my favorite directors, Martin Scorsese, is guilty of that. The music should be more integral to the film. It has to be. I try to choose all the composers and sometimes the sound mixers for my films. For instance, all the Jamaican films I did, like Countryman, were scored by Wally Badarou, who understands the music and what it means to the film.

Records, studios, films-now DVD and the Internet-how is creativity, yours and everyone else’s, faring in the age of convergence and multiple media? MP3? How is media affecting content quality?

The interesting thing is, I don’t think they converge all that much. When these large conglomerates get a hold of [media companies], they are led by administrators and strategic planners, and as a result, they don’t make as much use of their potential synergies as you might think. From the Palm Pictures point of view, everything is centralized with me and my team of management, and we can consider all the possibilities of a project-movies, music, Internet. What I think we’ll see is the dawn of a new generation of independents, as we did in the 1950s.

You sold Island to PolyGram. Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss did the same with A&M, and now they’re suing [PolyGram owners] Universal not only for unpaid royalties, but because they claim that the sales have undermined the vision they intended for the label. How do you feel about that and about what major conglomerates have done with Island and with the music industry in general?

I think that’s something they had in their contract. It was expressed at the time the company was sold. In my contract, I frankly didn’t think about that. On the other hand, once you’ve sold something, that’s usually it. The problem with the way that conglomerates affect the entertainment industry is that you don’t get any long-term artist development. As independents proliferate, you’ll get more of that again. I also think, though, that Atlantic Records is an extraordinary exception to that, and still is. So it shows that big isn’t necessarily less creative.

Finally, after all the time you’ve spent investing in Miami’s entertainment and real estate infrastructure during the last 30 years, what do you think about what’s going on in Miami right now with studios and music?

I’m very excited about it. It’s something I’ve believed in for a long time, and I may have been a bit early. But I truly believe that Miami can be a serious music center. There is a great mix there of great music, which till now has been underexposed. But with the focus now on Latin and Caribbean music, Miami is the natural capital of all of that.